There came a time when the eldest girl of the six kids living in an old house on the hill could bear the caregiving duties no longer and fled her home. She left carrying only the clothes on her back. After travelling for days and begging for food, she came to a settlement of tribal dancers who lived in tents, lit by earthen lamps, crows lined around the perimeter. The girl asked for shelter and was brought in front of the caretaker everyone called Mother.

“This is not a refuge for a girl who ran away from home,” Mother said, her upper lip twitching.

“Everyone in my family is dead,” the girl said, her eyes so bright, as if with fever.

“Very well,” Mother said, and picked up a round mirror in the dip of her long skirt. The girl felt her sharp gaze on her back as she walked away from Mother’s luxurious tent into an ordinary one with an old cot and a rusted trunk to keep her few things.

•

Mother was relentlessly lazy and surrounded by beautiful, sly women deft at dancing and singing, at making their thoughts her own. She spent the day in her tent, lounging on a plush mattress, her feet underneath her hips, her large body looking like a twisted knot. The girl served Mother strictly to the letter—every dawn, she walked two kilometres to get freshly squeezed cow milk, washed her clothes, starched and ironed them, applied buffalo curd on her puffy, blotchy face, and gave her a luxuriating sandalwood bath. The work led her from task to task as though a finger slipping through the rosary. In the evenings, the girl lingered around the dancers getting ready–– rubbing a chalk of colour on their lips, pink, fluorescent dust on their cheeks, tapping their wrists and necks with perfumes from bulbed bottles, wearing lehengas and covering their faces with bright, transparent veils before stepping on the stage. Earnestly, the girl watched them dancing with a column of earthen pots on their heads or landing straight on a steel plate after somersaulting in the air. Later the dancers would return to their tents, their mouths leaned into each other’s ears, wreathed in murmurs about the men who whistled at them. Alone in her tent, the girl stared at the ceiling and thought of her family, her mother’s anger uppermost in her mind, if one of them wandered this far looking for her. Somehow being invisible in the settlement soothed her for the time being. She fell asleep dreaming as one of the dancers––a small flask balanced on her forehead as she whirled and twirled, once so fast she woke up. It was then she decided to practice on her way to get the milk––standing upright on grazing buffaloes and donkeys—her first step toward balance. Mind before body, she kept chanting, like she’d heard the performers when they practised. In a few months, she could tiptoe on the feeding animals––crawl in narrow ditches and jump from the cliff into the river, let the gushing water bend and twist her like an octopus.

When she performed for the first time in front of Mother, everyone marvelled at the girl’s grace as long as she lip-synced to Mother’s sweet voice, since her own was coarse. The girl, beaming with joy, realised no other part of her life had mattered, all of it had been gathering pace toward this moment.

Soon the girl established herself as the nartaki, the main dancer. The knowledge of what had to be done steadied her feet and arms— she performed blindfolded, throwing small, sharp knives at the audience without injuring anyone. Some of the dancers warned Mother of the growing popularity of the girl with the audience, her friendship with powerful men from the ruling parties in the adjoining cities who regularly came to watch her. Afraid to lose her influence, Mother invited the girl into her tent, offering her koel’s blood as a means to sweeten her voice, the girl’s portion mixed with venom from a deadly scorpion.

As the girl drank the dank, pungent blood, something snatched her outside of her body. When she returned to herself, the reflection in the mirror showed her awash in blood, her right pinky shaped like a stinger and Mother’s body open like a split pomegranate. When she stepped outside Mother’s tent, she felt she had walked out of a womb, covered in Mother’s fat and gore, her sight gleaming with the wonder of a newborn. Some women shrieked, some stood in silent disbelief, their collective foreheads covered in a hazy terror. She asked one of them to transfer her belongings into Mother’s tent and real- ized how hypnotizing she sounded. When some women suggested they cremate Mother, some talked about a burial, the girl-bird sug- gested to feed it to the crows, and all the women brought their knives and swords, smiling and chopping away, as if nothing happened.

The girl-bird massaged her teeth with cloves, applied powdered snakeskin on her eyelids like Mother used to. Once a month––a frequency determined by trial and error to keep her voice melodious she drank koel’s blood tinged with scorpion’s venom, and to avoid killing anyone, she chained herself to the strong bedposts until she returned to herself, her hair dishevelled, her eyes crimson-flecked. Koel’s blood made her skin shine like a mirror. When she sang, her voice rose above everything—the stage, the streetlights, a perfect pitch, translucent without a rupture, like it belonged not only to humans but everything breathing around her. When she danced, the cows and dogs herded, the snakes spiralled, the birds flew in a circular pattern, the men, women, and children swayed as if in a trance, their eyes mesmerised to a splendour of colours and cadence.

It went on until the girl-bird fell in love with a local municipal officer who used to visit during her performances. She didn’t care that he had a paunch and his eyes dropped to his chin. She didn’t care he was married with two older boys age appropriate to be her suitors. He was the only one who seemed unfazed by her voice. During the day they smoked pot, got on his motorbike. They drove across the fields and the long winding roads, through the city, as fast as they could. “My queen,” the officer slurred at her, then kissed her fingers and arms, elbows, his left hand grabbing her thigh through her skirt. She twisted and twitched in arousal. Intoxicated, their bodies wilted into incomplete sex until the girl-bird woke up to mosquitoes buzzing in her ears, a lurking moon behind a cloud like a shy bride.

When the officer’s wife came to know of her husband’s indiscretions, she threw him out of their house and cursed the girl-bird to die from the sweetness in her voice. Homeless, the officer started living in the settlement. Together, he and the girl-bird drank and slept until late. The performers considered it a bad omen, a man cursed by his wife living amongst them, and advised the girl-bird against it. Sagged under liquor and love, she laughed it off and grew reckless with feed- ing the crows and disciplining the dancers, cancelling her performances. Gradually the crowds shrank and most of the women left to look for other settlements. Once the neglect took over, it was forever.

In the absence of koel’s blood, the sound in the girl-bird’s throat crystallised into sharp lumps of sugar, her neck swollen, ruptured, unable to turn, move. It was only when she couldn’t speak that she realised the municipal officer was deaf—he made out the words by watching her lip movements and therefore was not under her spell. Lying on an old cot in her tent holed in the wind and rain, she knew he had left; it had been days since she had seen him. She could feel the space around her tighten under the force of loneliness and loss. Syrupy tears glaciered on her cheeks. Attracted to the sweetness, the ants darkened her face, their antennae and legs stuck in the viscous fluid, their bodies mounting on top of each other. The sound that had been staggering in her body came out like a fatigued song and her warm mouth opened, an orifice for the ants to sink as if in quicksand.

Eyes closed, she imagined a soft remembrance of her house on the hill until the front door flung open and a heap of tattered possessions with no familiar sounds of her parents or siblings unfolded before her. A shadow like Mother’s slipped across the window. Giant crows flew around under a ceiling of dim lights, their young ones shrieking from the attic, koels with wrung necks sprawled on the living room floor, rotted beyond recognition.

……..

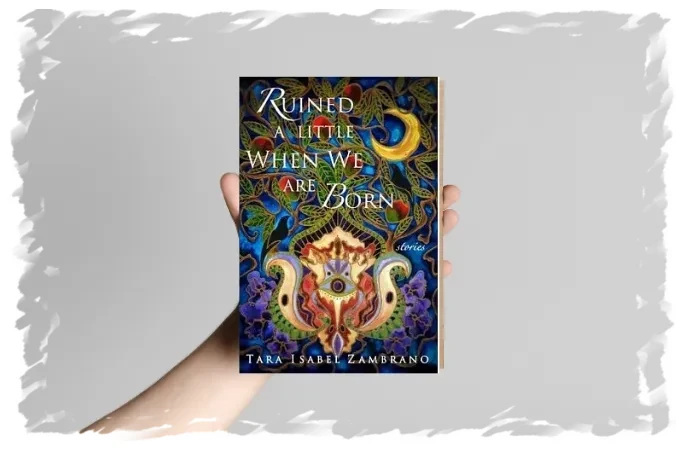

We’re pleased to introduce Tara Isabel Zambrano, an Indian-American writer, to FemAsia readers. The above story is part of her collection, Ruined a Little When We Are Born, released on October 15.

Zambrano’s work is marked by a blend of realism and subtle, supernatural elements, exploring themes relevant to the Indian diaspora, particularly family and identity. Her writing often delves into personal struggles and complex emotions that shape her characters’ journeys. Having lived between India and Texas, Zambrano brings a multicultural lens to her stories, weaving connections between tradition and modernity.

In Nartaki, Zambrano examines how heritage and individual identity intersect, a theme aligned with FemAsia’s dedication to highlighting diverse voices. We look forward to sharing this story with our readers and offering a glimpse into Tara Isabel Zambrano’s thoughtful, nuanced storytelling.

Founded in 2006, Dzanc Books champions innovative writing and fosters literary communities, publishing award-winning fiction and nonfiction from acclaimed authors like Roy Kesey, Yannick Murphy, and Laura van den Berg. Beyond publishing, Dzanc supports literary education through their Writers-in-Residence Program in public schools, hosts the Disquiet International Literary Program in Lisbon, and awards three annual Dzanc Prizes for excellence in fiction and nonfiction. Supported by the National Endowment for the Arts and Ann Arbor Community Foundation, Dzanc connects readers to bold, boundary-pushing literature, distributed widely through Publishers Group West.