Documentary films are invariably about ‘them’ made by ‘us’ for consumption by ‘us’. The subjects of these films tend to be constructed as ‘less powerful others’, whose difference from ‘us’ make us appear as ‘normal’. Audiences generally use these texts to assert their ‘normality’ too: “We are not like them, we are more fortunate, more privileged, poor them, how brave…”. Our project has been to question and subvert the ‘normal’. Many of our films bear witness to this concern. One line that we always carry in our heads comes from Harrison, a Nigerian prison poet from our film YCP 1997 (set in Yerwada Central Prison in 1997). He asked us a startling question: “Do you think you are free?” and answered it with an even more startling answer: “It is only a matter of the size of the prison – we live in smaller prisons and you, in larger prisons…”

In many of our films, we have explored the connections between these ‘prisons’. This helps us amplify the dignity and agency of our subjects rather than increase the divides that underlie the project of documentary filmmaking. Some films offer the opportunity to work in close collaboration with our subjects. Naata (2003), set in Dharavi, Mumbai, grew out of our interaction with Bhau Korde, a retired school clerk and Waqar Khan, a small garment manufacturer, whose inspiring work on communal amity, after the 1992-93 riots, we had been following for several years. This story of how Waqar, Bhau, and the people of Dharavi have, on their own accord, produced and used various media materials for communal amity (ranging from posters to videos and audio cassettes) has an important lesson for all of us in these troubled times. We feel that it is crucial to share stories of hope and struggle in our present fractured world, stories that give us the courage to go on. We also wanted to explore the language of a non-confrontational dialogue with our viewers that gently prompts them to look within, to reflect on personal prejudice.

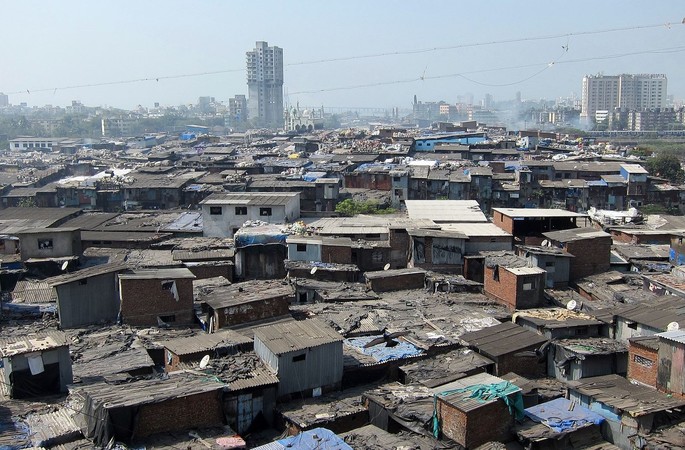

As Asia’s largest slum, with a population of over 800,000, Dharavi has often been represented as a breeding ground for filth, vice and poverty, full of ‘migrants’, whose right to live in the city is often questioned by vigilante citizens’ groups and right-wing politicians. The film attempts to question these dominant representations of Dharavi in the popular imagination.

Dharavi is shown as having a long history, with migration taking place from the late 19th century. It is a productive space and plays an important role in the economy of the city, as it is one of the major hubs of the informal sector that produces commodities ranging from food products to leather goods that cater to a large export market. The film pays tribute to this creativity, vitality, and enterprise of Dharavi.

Today, Dharavi has become a popular destination for filmmakers, researchers, development tourists and their ilk. As Bhau says:

If you walk around Dharavi, you are bound to encounter at least 10 to 15 people with paper and pen in hand, doing research, collecting data. So much has been written about Dharavi, so much paper – more garbage than we in Dharavi could ever generate! Sometimes I feel that perhaps it is good for them if Dharavi remained as it is. If it remained the same, a lot of research could be done, films could be made. Many things can be done (Bhau Korde, a social activist from Dharavi, in Naata, 2003).

We felt that the sheer energy and inclusiveness of informal grass-roots initiatives for communal amity raises several uncomfortable questions for us, so-called modern, middle-class, secular, urban beings, which we need to reflect on. We thought that the film needed to move beyond a ‘feel good’ story of the impressive work being done by Bhau, Waqar and the citizens of Dharavi. Hence, in terms of the structure of the film, we have introduced an element of reflection, through ‘our’ stories which could possibly lead to a critical and active viewership. These, we thought, will be spaces for the audience to reflect on their own ‘stories’.

Thus, the film weaves together four different narratives: the stories of Bhau, of Waqar, of Dharavi, and also our own ‘story’, which uses a visual register very different from the rest of the film.

Their narrative of their families’ lives is told through material culture—toothbrushes, toys, vegetables, and other objects. They describe this documentary as a sort of “self-reflexive ethnography, low budget.” It negotiates the middle-class origins of their film and its relationship to the subaltern classes that make another film through gentle self-humour so that while the subaltern speaks, the viewers/directors are not voyeurs nor patronising “others” but allied media (Srinivas, 2007:313).

The use of trivial everyday objects that are markers of middle-class identity, placed within a sanitised, clinically white rectangle is an ironic comment on our normal middle-class selfhoods that we uphold with such seriousness, often denying similar selfhood to the millions of labouring others who live in the shanty towns just beyond our high rise apartments, without whose unrecognised and underpaid work the city would collapse.

‘Naata’ was made 18 years ago. Many things have changed in the interim years. Waqar Khan is no more; he passed away in April 2009, of a sudden heart attack. His son Gulzar continues his work for the peace and welfare of Dharavi. Bhau Korde, now in his 80s, is still socially active and has mentored a new generation of peace activists. Dharavi is in the process of gentrification and is now prime land right in the centre of the city. And the themes that Naata explored are ever more relevant, with the increasing rise of the politics of hate and the dispossession of the migrant poor in the city of Mumbai. The film can be seen here:

Naata (The Bond, 2003, 45 mins., Hindi with English subtitles)

http://www.monteiro-jayasankar.com/films/2003/naata-the-bond.html

References

Srinivas, Smriti. Review of The Bond, Visual Anthropology, Volume 20, Issue 4, July 2007, pp 313 – 314 313 – 314