In my first article in FemAsia, on 15th January 2018, I wrote about the challenge of creating educational material for women refugees, in an attempt to share some concerns that have come up, as the need for building new educational materials that catered for the new (refugee) populations in Greece started to grow.

Since the linguistic education for refugees and migrants is a constant concern and interest of mine, I would like to expand on my previous concerns and attempt to self-criticise implicit negative assumptions we make for women from unfamiliar cultural and religious backgrounds.

In my previous article, I wrote that: If religious allegiance is an important aspect of the life of people in general, and refugees in particular, how can we not take them into consideration and bring them into a discussion?’, suggesting that a strict Muslim insight into life comes into conflict with the feminist outlook.

Here I would like to take the issue further, and examine whether, as ‘women of the west’, I, and others like me, actually have the right to present a feminist outlook that is out of context, and perhaps without much meaning for our recipients.

Since my last article, I read about the movement مساواة Musawah (equality), according to which Islam does not, de facto, express hatred and prejudice for women, but it is the patriarchal power that makes Muslim men interpret Islamic text as it suits them.

Musawah actually empowers women to develop interpretations and norms that could affect their lives positively, calling upon them to strive for legal and institutional changes in their societies (Segran, 2013).

For women, including many feminists, whose realities, languages and cultures are not prominent or familiar to those involved in analyzing women’s lives, sexism and racism intersect, and go hand in hand, and cannot be understood if looked at in isolation.

According to Abdulhadi et al. (2011), there is not one universal experience for women, but the female social gender is constructed through a variety of political issues that co-exist and often overlap.

As Muadi Darraj (2011) suggests, women from the Arabic world come from a great variety of socio-economic backgrounds, spaces, religions, ideologies and professions. Some may be forbidden to leave the house, while others may have full family support and encouragement to be independent and seek a career.

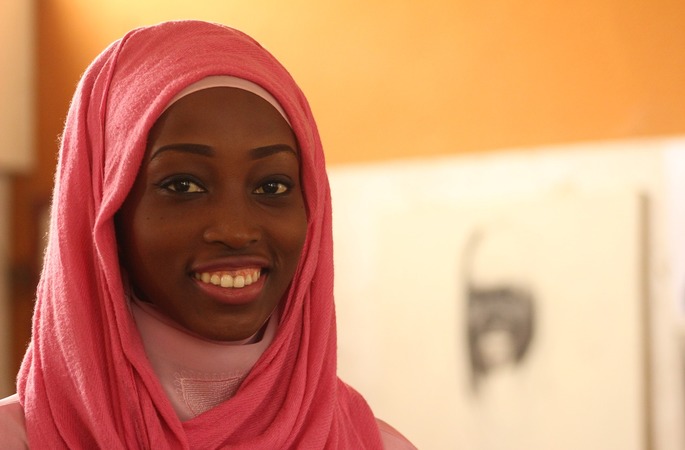

However, it is the invisible woman or the ‘faceless veiled woman’ as described by Muadi Darraj (2011), that has become the prominent image of the Arab/Muslim woman.

As Muadi Darraj (2011) suggests, feminists in the West do not take the time, or make an effort, to discover and promote the work and struggles of (Middle) Eastern women, and the ways women in the Arab-speaking world organise and empower women.

As someone who is involved in education and training, I am of the opinion that Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies (CSP) (Paris & Alim, 2017) may be an approach that could do justice to this lack of balance between a western feminist approach and the need to cater for the complexities of Arab-speaking women.

According to the CSP approach, issues concerning cultural values need to be personalised and connected with reality, in ways that enable educators and students to assess, on a personal level, the complexities and peculiarities of people within their respective communities.

To this end, the use of identity texts, (Cummins & Early, 2011), that is texts that bring forward images of ‘otherness’ in order for us to get to know and relate to these realities, turning them into ‘identification texts’ (Kompiadou & Tsokalidou, 2014), may be a powerful means of giving voice to the invisible women in our contexts

We close this small contribution with one identity text by Susan Muadi Darraj:

I am haunted by a constant companion called The Arab Woman. When I shut myself alone in my home, she steps out of the television screen to taunt me. In the movies, she stares down at me just as I am starting to relax. As I settle into a coffee shop to read the newspaper, she springs out at me and tries to choke me.

In the classroom, when I tell my students that I grew up in Syria, she materialises suddenly as the inevitable question comes up: “Did you wear a veil?” That is when she appears in all her glory: The Faceless Veiled Woman, silent, passive, helpless, in need of rescue by the west.

But there’s also that other version of her, exotic and seductive, that follows me in the form of the Belly Dancer.

(Muadi Darraj, 2011: 255-256)

References

Abdulhadi, R., Alsultany, E. & Naber, N. (eds) (2011) Arabs and Arab American Feminisms. NY: Syracuse University Press.

Cummins, J. & Early, M. (Eds) (2011) Identity texts the collaborative creation of power in multilingual schools. UK & Sterling: Trentham Books.

Kompiadou, E. & Tsokalidou, R. (2014) Identity texts. Polydromo, 7, 43-47.

Muadi Darraj, S. (2011) Personal and Political: The Dynamics of Arab American Feminism. In Abdulhadi, R., Alsultany, E. & Naber, N. (eds) (2011) Arabs and Arab American Feminisms. NY: Syracuse University Press, 248-260.

Paris, D. & Alim, H.S. (eds) (2017). Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies. Teaching and Learning for Justice in a Changing World. Columbia University: Teachers College

Segran, E. (2013) The Rise of the Islamic Feminists. https://www.thenation.com/article/rise-islamic-feminists/

Tsokalidou, R. (2018) We write your rights. FemAsia. Asian Women’s Journal. http://femasiamagazine.com/we-write-your-rights/