What is left of the inner mind when the world turns more cruel… than ever before? When it reels from inflicted blows – pandemic, war, starvation, climate devastation or all these together – what happens to the fabric of the mind? Is its only option defensive – to batten down the hatches, to haul up the drawbridge, or simply to survive? And does that leave room to grieve, not just for those who have been lost, but for the broken pieces and muddled fragments that make us who we are?

Jaqueline Rose, “To Die One’s Own Death” (1),

Written at the height of the second wave of the Covid pandemic, as a meditation that is as heart-wrenching in content as it is breathtaking in scope, Jacqueline Rose traces the emergence of the concept of the ‘death drive’ in Freud’s oeuvre. As Rose reminds us, Freud himself tried fiercely to put out the idea that events in his personal life had no bearing on his theoretical work. And yet historians have now documented how the death of his favorite daughter, Sophie Halberstadt-Freud, during her third pregnancy from complications arising from Spanish flu, was an unmistakable decisive event which provided the context for the appearance of this most difficult, speculative concept in Beyond the Pleasure Principle. Moreover, as Rose also reminds us, beyond the fact of their historical coincidence, the plague and the war [/WWI] were two piled up disasters. The destiny of one was wound up with the fate of the other. As such, they form the limit-points of Freud’s thought. In reflections which constantly intercut between events in Freud’s own life and the disastrous response to Covid by the narcissistic male-leaders of the world today, Rose seems to be suggesting patterns: as in 1916, so in 2016 and beyond, in the era of Trump, Bolsonaro, Modi, Erdoğan, Orbán, Duterte et al.

Beyond the Pleasure Principle is one of the most important works of the second half of Freud’s life. It marks the culmination of his thinking on the topography of the mind and introduces the new dualism of the drives. The idea of an unconscious demonic principle driving the psyche to distraction can be said to sabotage once and for all the vision of man in control of his mind. Prior to this Freud had been elaborating on the repetition compulsion, which he had first identified in soldiers returning from battle who found themselves reliving their worst experiences in night-time and waking dreams. Slowly tracing this tendency from the front to the consulting room (patients wedded to their symptoms), Freud astonishingly concluded that such a compulsion is a property of all living matter. The urge of all organic life is to restore an earlier state of things. ‘The organism wishes to die only in its own fashion.’

If the death drive is one of the most controversial of Freud’s theories, Rose reminds us that that it is because it turns violence into the internal property of everyone. What drives people crazy in wartime is their capacity, after a lifetime of prohibition and restraint, to take violence upon themselves. That tyranny is the silent companion of catastrophe (2) was also flagrantly apparent in the behaviour of leaders of several nations across the world through Covid. Yet paradoxically for Freud there is also nothing worse than the idea of death as part of a string of accidents. Through the merciless randomness of their deaths, the victims of the pandemic and WWI, Freud suggests, were being deprived of the essence of life.

However as she traces a complex chain of ideas, Jacqueline Rose notes that although Freud remarked that the impulse to human empathy is difficult to explain, that compassion can often be a veil for narcissism, there are also moments in Beyond the Pleasure Principle when the bare outlines of such an impulse can be found. In such moments, Rose senses that something is working through Freud’s text, a ‘socius primitive’ in Derrida’s reading, or a new form of common life, never more needed than now, which sheds the common pitfalls of the singular ego. Contrary to the brutal fault lines of race/class/gender that determined who would be hit by the pandemic or sacrificed in the Great War, Rose proposes that Freud was tracing here the faint outlines of a life in which the pain of the times could be shared, and in which every human subject, regardless of race, class or sex would be able to participate. This, according to Rose, may be what it means to struggle for a world in which everyone is free to die their own death. Death in a pandemic or war — or a tsunami – [for Freud] was/is certainly no way to die.

The Indian Ocean tsunami on 26 December, 2004, killed an estimated 227,898 people across 14 countries. It is one of the deadliest natural disasters in recorded history. In India, the tsunami reached the states of Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu and Kerala, along its southeastern and southwestern coastlines respectively, about 2 hours after the earthquake. Along the coast of Tamil Nadu, the 13 km (8.1 mile) Marina Beach in Chennai was battered as the tsunami swept across the beach, taking morning walkers unaware. But the worst affected area in Tamil Nadu was Nagapattinam district, with 6,051 fatalities. Most of the people killed there were members of the fishing community.

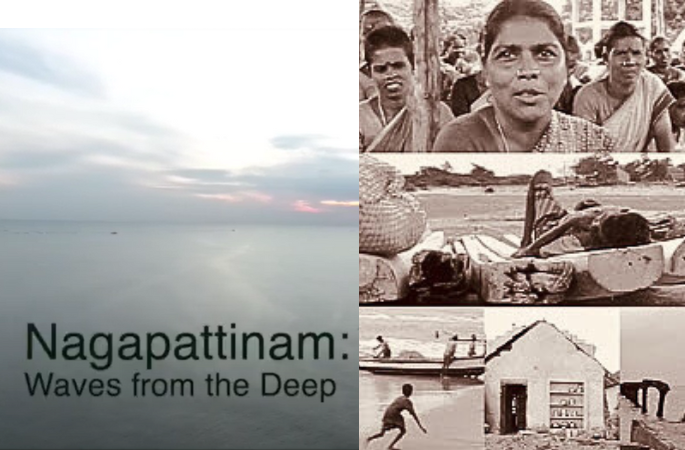

Running to around 75 minutes, Swarnavel Eswaran’s documentary, Waves From the Deep, (2018), revisits the coastal town of Nagapattinam over a period of twelve years, from 2005-2017, to understand the depth and scale of that monumental tragedy that scars the town till this day. The documentary has five broad sections. It begins with archival footage of interviews with the two main protagonists around whom the entire narrative is structured. The first of these is the district collector of Nagapattinam, Dr Radhakrishnan, (representative of the ‘state-machinery’/ the TN govt). The second protagonist is Dr Revathi, Coordinator of the NGO, Vanavali, who fiercely questions the response of the state to the tragedy and its abdication of responsibilities towards its most vulnerable citizens.

The second section takes stock of what the NGOs actually did in terms of providing food, shelter and livelihood/ rehabilitation to those affected. The main protagonist of this section is Ms Vanaja, Coordinator of SNEHA, the longest-serving NGO in the area. Ms Vanaja also points out shortcomings of the state’s initial response to the tragedy, especially the way in which almost all relief-measures overlooked two of the most-affected sections of the fisher-community: the fisher women and children. This segment includes representatives from local women’s self-help groups as well and recounts for the audience the demanding nature of the many economic and social roles that women of this community perform as well as the unique challenges/ forms of discrimination they face.

The third section focuses on orphaned-children, mainly at the Annai Sathya Shelter Home. Dr Radhakrishnan, in his first ‘live’ interview, tells the narrator that 250 children were orphaned while 705 lost one parent. The gut-wrenching stories of death and loss narrated by the children apart, Dr Revathi subsequently reminds the narrator that the state-response of either adoption or institutionalization completely overlooked both the close-knit community-structure of the fisher-folk as well as the emotional needs of the orphaned children. A child whose life has been woven around the rhythms of the sea will be a total misfit if s/he is sent off to live in a landlocked city such as Bangalore.

The fourth segment is an engagement with representatives of, broadly, the NGO sector: Annie George, from the NGO Coordination Committee, representatives from Christian Aid, World Vision as well as an interview with the Council Chairman of Velankanni.

The final section returns to the main protagonists. As Ms Revathi recounts the ten years since the tsunami, she concedes that she has reconsidered some of her earlier criticisms of the government. As she looks back in 2017, she also acknowledges the good work that has happened in Nagapattinam in which NGOs have also played a significant part. This is followed by local people recalling Dr Radhakrishnan with great warmth and affection, now that he has been transferred on a different posting. The documentary ends with the sombre commemoration ceremony of the tsunami in 2014, as the fisher-community revisits that terrible day. There is a procession of grieving men and women and a school exhibition. In the last sequence of the film, the camera pans upwards from between two fishing boats and then cuts to tranquil shots of the pier with the nadeeswaram playing in the soundtrack, recalling the initial scenes of the documentary.

The term ‘documentary,’ as Shoma Chatterjee (3) reminds us, is actually a very complex one. Quoting the activist documentary film-maker Madhusree Datta, she points out that the implied notions of ‘authenticity’ or being ‘factual’ that the ‘documentary’ tradition is generally associated with comes from the popular tendency of treating ‘fact’ or ‘truth’ in turn in a kind of simple, linear fashion; to see a text or representation as fixed and immobile. But this of course is in marked contrast to the idea of ‘creative treatment of actuality’ which was John Grierson’s working definition of the same. Furthermore over the decades, and with the huge momentum that this tradition has gathered across cultures, the idea of the ‘documentary’ film today is much more sophisticated.

There has emerged a significant body of writing on the documentary tradition in India too with Peter Sutoris’ Visions of Development: Films Division of India and the Imagination of Progress, 1948-75, (2016) being one of the pioneering works (4). Analyzing about 250 documentary films made by Films Division of India between 1948-75, Sutoris examines the subtle shifts in the postcolonial state’s ‘developmental’ ideology from Independence/1947 to the Emergency years of 1975- 77. By comparing these documentaries with late-colonial films on ‘progress,’ the book highlights continuities with as well as departures from colonial notions of ‘development’ in modern India. As many commentators have noted, Sutoris’ book was pathbreaking because many of the documentaries he analysed had never been discussed before in scholarly literature on Indian cinema. Furthermore, the book wonderfully highlighted the basic thrust of government newsreels in the classical years of nation-building: most of them were concerned with popularizing government schemes/ ideas on economic planning and industrialization, family planning and other similar schemes aimed at ‘civic education’ and the ‘integration’ of ‘tribal’ peoples (Adivasis) into mainstream India.

Extending Sutoris’ arguments, documentary filmmaker Paromita Vohra (5), in her capsule summary of the movement, teases out some important features of the documentary tradition in India in its formative years. She notes the ideological distinction that was made between ‘documentaries’ and ‘cinema’ in the 50s/60s with the former bestowed with a certain social prestige which came from the fact that documentaries and their makers were seen as ‘socially conscious’ artists not invested in box-office returns. Furthermore she points out an important stylistic feature shared by many first-generation Films Division documentaries, especially regarding the use of the first person pronoun. While the ‘I’ was not used in most of these documentaries, either by their makers or by the people interviewed in them, the disembodied voiceover/point-of-view which they all shared represented the voice of this ‘alternate’ elite completely invested in Nehruvian ideas of ‘social uplift’ and ‘education’ of the masses. Vohra then reminds the readers of the stylistic breaks that emerged as J.Bhownagry took over directorship of Films Division from Ezra Mir. The 1960s saw the emergence of a generation of documentarists who were much more experimental in style and open to incorporating subjective experiences, intimate feelings, collage styles and a range of other formats that would radically challenge the idea of a stable first-person narrator.

By the 1970s, serious documentary making in India had shifted completely to the ‘independent space’. The major protagonists of the time were ‘political’ documentary filmmakers in the tradition of Anand Patwardhan and Deepa Dhanraj, influenced greatly by the Third Cinema Movement/ the idea of a left-of-Centre ‘people’s cinema’. But this paradoxically created, Vohra notes, a new kind of selfless film. The desire to be ‘the voice of the people’ meant that the documentary contained no or minimal commentary and instead used interviews with affected communities to convey a message. By the 90/ post-liberalization, documentary practice in India had become even much more diverse as well as complex: it now included the ‘personal’ in the documentary work of Mani Kaul and in the political-essay films of Amar Kanwar as also the use of the intimate/biography mode by feminist documentary makers such as Reena Mohan. In fact, writing in the euphoria of the 2004 elections results, Geeta Kapur thinks of the ‘critical documentary’ as the new artistic avant-garde (6).

These developments are all of importance in a discussion of Eswaran’s documentary too. Working within the ‘independent’ space, Eswaran’s documentary uses a collage of stylistic features. Broadly in the tradition of the ‘political documentary,’ the body of the film, as already noted, is structured around interviews, (some archival and some live), with two main protagonists: Dr Radhakrishnan and Dr. Revathi. Both protagonists respond to questions put by the narrator, either live or via archival footage. Eswaran also live-interviews many members of the fisher-community, especially women and orphaned children who recall their traumas and/or tell us of their extremely vulnerable conditions even in the present. There is also a definite point-of-view that the documentary takes at the end. This is neither the point of view of the ‘state’ (/Dr Radhakrishnan), nor of ‘civil society’ (/Dr Revathi) nor even of the fisherfolk themselves. Rather it is very much Eswaran’s own position on the desirable relationship between state and civil society activists/ citizens. Such a film on the 2004 tsunami is thus also in sharp contrast to, for instance, the essay-film by R.V.Ramani, My Camera and Tsunami (2006/11), which is a completely personal recollection by the film-maker of the horrific loss of friends and comrades (as well as his beloved camera) on that fateful day (7).

Looking back over the last century, Laura Mulvey (8) astutely notes how the development of new electronic and digital technologies in the new millennium have completely transformed classical conditions of film-spectatorship. In this transformed context Mulvey argues, first of all, that earlier therorisations of cinema’s aesthetic polarities debated through its critical history, such as between classical and ‘alternate’, fiction versus document or grounding in reality versus potential for fantasy, need to be rethought. Using the psychoanalytic concept of trauma and deferred action, (nachtraglichkeit), Mulvey then meditates on how the new, many and ultimately playful ways of relating to the screen enabled in the new electronic/ digital era can, paradoxically, re-animate concerns of the avant-garde of 70s Hollywood so that we may yet become, what she calls, the intellectual or pensive spectator – a spectator who is more engaged with reflections on the visibility of time in cinema, and by association questions that still seem imponderable such as death and the fragility of human life rather than remain a spectator who is fetishistically absorbed in the image of the human body.

Mulvey’s mediations carry rich resonances for Waves From the Deep and its complex play on time. Shot between the summers of 2005-2017 (/the drone shots), it is an actual material record of the of the transition from analog to digital technology in the crucial initial decades of the new millennium. It charts the trajectory of low-end video technology, as this evolved from standard definition videos shot on mini-DV tapes in 2005, using the Sony 150 and 170, to later DSLRs in 2010, to finally high definition go-pro cameras in 2017. The film also uses shots taken with earlier models of cell phones. Furthermore, by repeatedly returning to Nagapattinam the documentary uncannily mimics in its form Freud’s notion of trauma, as the film tracks the journey of disaster-relief and management, displacement, resettlement, problems of women and children, and a host of allied issues for over a decade after the eventful day. Narratively, the film ends in 2014, at the sombre, tenth-anniversary commemoration ceremony as friends and relatives mourn their lost ones. This is preceded by a concluding backward glance by Dr Revathi who re-assesses her earlier criticisms and introspects on how the years she has spent with the orphaned children at Nagapattinam, at the school that her trust has built, has helped her understand the long and complex process of ‘grieving.’ Dr Revathi’s recollections are followed by fond memories of the fisher-folk who miss Dr Radhakrishnan (/’appa’) now that he has been transferred. In startling ways, therefore, the documentary suggests through its form that it is only after a decade that the fisher-folk or common people like ‘us’ might have the words/ the language to comprehend the enormity of the losses/ the trauma suffered all those years ago.

The critic Peter Brooks (9), in a context different from but related to the discussions above, comments on the significance of repetition in narrative cinema (/fiction film) and relates it to Freud’s concept of the death drive. Repetition in a text holds back its forward movement, postponing or delaying the end. Moreover the narrative form of the fiction film into which the principle of delay translates can vary significantly, eg. the aesthetic of suspense or the intrusion of digressions or the ‘aleatory strolls’ that Giles Deleuze associates with the loosening of the ‘movement-image.’ For Deleuze such a pause in narrative film, what he called the ‘time-image,’ emerged out of the ruins of World War II. In Deleuze’s vision, Italian neo-realism reflected the shock left by the war and the need for a new cinematic way of thinking about the world. This shock demanded a film aesthetic driven not by a drive towards narrative organization and closure but a cinema of record and observation, one which would hesitate and confront the audience with a palpable sense of cinematic time that would lead back, from the time of screening, to the time of registration, the past.

Working with a complex idea of time/ causality, Brook’s observations are deeply relevant to Waves From the Deep. The time of ‘registration,’ in the immediate aftermath of the tsunami, also represents a significant moment in the trajectory of the postcolonial nation-state. This subject is too complex to discuss in detail but there is now a rich body of critical discourse analysing the many ways in which the ‘passive revolutions’ that marked the decolonization movements of Asia/Africa/Latin America in the 1950s/60s reworked classical idioms of liberal democracy in unprecedented ways (10). However by the 80s/90s these postcolonial states in turn found themselves overrun by a new all-encompassing market logic(/globalization). In complex ways since then, many of these postcolonial nations have also witnessed the emergence of different kinds of populist mobilizations.

The main protagonists of Eswaran’s documentary need to be located on this invisible scaffolding. As already mentioned, Dr Radhakrishnan directly represents the Tamil Nadu government/ the ‘state-machinery’ while Dr. Revathi represents the space of civil society/ non-governmental organisations. The sharp ideological differences between their initial positions are located on broadly the ‘rights’ versus ‘philanthropy’ axis. As empathetic representative of one of India’s most prominent states, Dr Radhakrishnan is painfully aware of the limitations of the state-machinery and welcomes the participation of well-meaning NGOs at a time when the sheer scale of the devastation has overwhelmed state-capacity to provide relief/ assistance to hapless citizens. On the other hand, as representative of ‘civil society,’ Dr Revathi is extremely critical of what she views as the state’s abdication of its responsibility to provide livelihood/aid/education/medical care in times of distress. Over and above the fact that most NGOs have no understanding of the kinship networks of the fisher-community and/or no understanding of the (personal and economic) needs of the fisher-women, Dr Revathi underlines a well-established critique of the NGO-machinery in general. Claims of aid from the state can be asserted as rights, by citizens. But within the NGO-world, help is re-coded as charity/aid/philanthropy and requires subservience/obsequy. Some NGOs also link aid to religious conversion. Thus the question that frames the initial segment of her interviews is broadly this: given that there was such an outpouring of help from all around the world, why did the state of Tamil Nadu not itself become the main fulcrum around which the entire rescue and resettlement programme was organized? Why did it outsource its most central function to (sometimes even shadowy) NGOs? (11).

Yet by the end of the film, as noted, she has changed her assessment. As she looks back she acknowledges that a lot of good work has also been done by NGOs : good-quality homes have been built, education in Nagapattinam schools is of high standard, livelihood is once again picking up. Significantly, she has herself now permanently relocated from Chennai to the fisher-town. Yet she also incisively points out the gaps that remain. She is prescient when she notes that the TN government used the disaster, and the annihilation of the possibility of organized resistance by its most vulnerable citizen-groups at the time, to push through legal and other civic infrastructure that would further devastate the fishing community and instead promote its neo-liberal agenda. Her observations echo concerns raised by Ms Vanaja from SNEHA Trust in the second segment. Ms Vanaja is similarly emphatic that initiatives such as the Sethusamudram Project or the East coast Highway or large-scale prawn-farming must be resisted. Ms Vanaja even points out how the local politician used the tsunami to set up liquor-shops in the town which lead to alcoholism among the men. How then should we, the audience, understand the decade that has passed? Should we conclude that it is, once again, the well-meaning middle-class activist, in collaboration with the well-meaning, paternalistic state, who will save and/or bring succor to the nation’s most vulnerable citizens?

In my opinion it is also at this point, in its conclusion, that the documentary demands the most informed reading from its audience. Our first-order reading of the film might well concur with Eswaran’s own position on the issue: that middle-class activists must work in tandem with rather than only in rigid opposition to, the ‘state’ (12). Such a broad-brush reading would however gloss over the unique nature of the postcolonial state and the completely new challenges its political structure poses to classical ideas of liberal democracy. This is again a topic I can only gesture to in shorthand, but political theorist Partha Chatterjee’s work comes immediately to mind. In a by-now celebrated response to Vivek Chibber, Chatterjee sums up the framing questions that have animated the Subaltern Studies project over the last twenty-five years thus:

The historical problem confronted by Subaltern Studies is not intrinsically a difference between west and east …The geographical distinction is merely the spatial label for a historical difference. That difference is indicated – let me insist emphatically – by the disappearance of the peasantry in capitalist Europe and the continued reproduction to this day of a peasantry under the rule of capital in the countries of Asia, Africa and Latin America.

[….]

Should we assume the same trajectory for agrarian societies in other parts of the world [as in Europe in the period of ascendancy of capitalism]? Does a different sequencing of capitalist modernity there not mean … that the historical outcomes in terms of economic formations, political institutions or cultural practices [here], might be quite different from those we see in the west? (2013: 74-75) (13).

As he tracks the contours of capital’s Eastern journey, the political formation that Chatterjee proposes as emblematic of the postcolonial world is that of ‘political society’ (14). Chatterjee is of course indebted to Antonio Gramsci here. For Chatterjee ‘political society’ is the terrain not of rights-bearing bourgeois citizens but of ‘populations’. It is a terrain where beneficiaries of state-support or targets of welfare schemes come together as communities/groups to negotiate for collective demands for livelihood/benefits. It is also a very recent social formation — the product of the democratic process in India/ the postcolonial state bringing under its influence the lives of subaltern classes and the resulting new forms of entanglement of elite and subaltern politics. Moreover the demands that emerge from this terrain involve critical transformations in property-rights and law as they exist. Emphatically for Chatterjee though it is this terrain that will, if allowed to mature, decisively rewrite the language of classical liberalism. It also from political society that the project of mass-democracy, in most parts of the world, will take on completely new and uncharted shapes.

The state of Tamil Nadu with its deep roots in social reform, especially of caste-politics (15), that formed the ideological core of the Dravidian parties, is central to Chatterjee’s conceptualisation of this new terrain. We get several snapshots/ hear voices from this subaltern terrain in Eswaran’s documentary too: from Ms. Maharani who delegates her subordinate to meet with the NGO-representative as she is smelling of fish; from the fisherwomen who tell us how they accepted NGO-aid even when it was inadequate such as being given silk sarees or as they negotiate for motorized carts to take the fish into town or in their demand that they be resettled in areas close to the sea. We see this in several interviews when the fisher-folk remind us that Muslims also helped in clearing dead-bodies; helped with food and shelter during those mind-numbing initial weeks. We also see similar glimpses in the interactions between the Nagapattinam children and Dr Radhakrishnan as they inform him that the local bus does not stop in their village and other difficulties they face in going to school. Yet towards the end these voices are submerged in Dr Revathi’s overall summation. This, as noted earlier, even as she points out that with the new thermal power-plants or initiatives such as the Sethusamudram project being pushed through, the fisher-community will be badly impacted.

Thus effortful task that Eswaran’s documentary ultimately poses to middle-class activists/ educators/ intellectuals is: how do we become truly ‘comparative’ in our understanding of the world? (16). One necessary step is perhaps to think seriously about ‘contingency’; to rigorously question linear ideas of historical causality as represented by the classical ‘realist’ narrative. Chatterjee reminds us that the idea of ‘contingency’ was very important both to Marx and Gramsci. I want to braid this further into a key concept mentioned several times earlier: Freud’s idea of trauma/ deferred action/ delayed registering/ nachtraglichkeit. I also want to draw forward Eswaran’s from documentary into our world today and the ways in which the neo-liberal economy, driven by the new data/technology companies, has interlocked chillingly with varieties of right-wing populisms across the world. This is also a stage of capitalism that is making large swathes of the working-class everywhere simply redundant: those that, for instance, were classified as ‘essential workers’ through Covid. This forward thrust of the tsunami story gains further resonances from the fact that it was also Dr Radhakrishnan who lead the TN state-government’s response to Covid-19.

The pandemic unfolded in India in two broad phases: initially as the migrant-crisis and then as the epidemiological one. The first phase, which manifested itself as a catastrophic humanitarian crisis, saw thousands of migrant/’informal’ workers, stranded without livelihood and shelter, being forced to physically walk back home to villages hundreds of miles away from the cities where they worked. Invisible in the public political sphere, and with crumbling public health infrastructure, the migrant workers were completely left to fend for themselves. In this context, noting how many state-governments, including TN, rushed to the frontlines, as well as the whole range of spontaneous subaltern networks that sprang up to mobilize resources and transportation to save the stranded workers from hunger and utter destitution, Ranabir Samaddar (17) similarly places his hopes of mass-democracy in the terrain similar to Chatterjee’s ‘political society.’ But this space of democratic subaltern mobilization remains extremely fragile and is increasingly under assault.

In the 2004 tsunami, before the giant waves hit the coast, the waters withdrew for a while and it is said that the ridges on the Indian Ocean bed were visible from the shore. What could not be seen by the naked eye however were the deep social cleavages on land. These cleavages, in many ways, have deepened. While the fisher-folk of Nagapattinam may only now be haltingly finding the words to acknowledge the trauma from two decades ago, other tsunamis loom on the borders of their lives. By looking back as well as ahead to the most critical issues of our times, i.e., the relationship between neoliberalism and mass-democracy, Eswaran lyrically and touchingly reminds us of the urgency of an entirely new ethics of care and healing for the planet (18).

NOTES

––––––––––––––––––––––––––

- Jacqueline Rose, “To Die One’s Own Death,” London Review of Books, (19 Nov, 2020) 1-10.

- See for instance Frank M. Snowden, Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present, Camb., Mass: Yale Univ Press, 2020. Snowden’s book meticulously traces the major epidemics in the Western world — from the bubonic plague to the small pox to the influenza pandemic—and the mass-surveillance techniques and other forms of state-power that were adopted as self-protective measures by states in response. A similar argument was made about Covid-19 in a celebrated essay by Yuval Noah Harari, The world after coronavirus,” Financial Times, March 20, 2020.

- Shoma Chatterjee, Filming Reality: The Independent Documentary Movement in India, ND: Sage Publications, 2015.

- Peter Sutoris, Visions of Development: Films Division of India and the Imagination of Progress, 1948-75, Oxford: OUP, (2016)

- Paromita Vohra, “ ” in Rashmi Devi Sawhney ed, The Vanishing Point: Moving Image After Video, ND: Tulika Books, 2022, pp.175-187. This is an excellent collection of essays on new trends in the documentary movement in India since the 80s/90s, ranging from well-known feminist groups such as the Rags Media collective to new film-collectives in Kashmir.

- Geeta Kapur, “” in Rashmi Devi Sawhney ed, The Vanishing Point: Moving Image After Video, ND: Tulika Books, 2022, pp.120-141.

- RV Ramani, dir, My Camera and Tsunami (2011)

- Laura Mulvey, Death 24x a Second: Stillness and the Moving Image, London: Reaktion Books, 2011

- Cited by Mulvey in Death 24x a Second: p.124.

- Political theorist Partha Chatterjee has been the most important theorist in this respect. See especially his, Nationalist Thought and the Colonial World: A Derivative Discourse? Delhi: OUP, 1986 and I am the People: Reflections on Popular Sovereignty Today, ND: Permanent Black, December 2020. For a striking psychoanalytic theorization of postcoloniality see Ranjana Khanna, Dark Continents : Psychoanalysis and Colonialism, Duke, NC: Duke Univ Press, 2003.

- On this point too, the literature is now vast, including the proliferation of NGOs in Tamil Nadu. For a broader and very much deeper philosophical rumination on the implications of the NGO-isation of the world and its relationship to the ways in which disciplinary boundaries were being re-drawn within the University already in the early decades of the millennium, see Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Death of a Discipline, Columbia Univ Press, 2005.

- It is important to remind the reader that is, by now, a huge body of literature, on the 2004 tsunami. Already in the immediate aftermath of the tragedy, there was an immense and rich body of work raising a whole gamut of extremely relevant questions: Could the tsunami have been averted with better early-warning systems? Why was India not part of the consortium whereby such information was already being shared across 26 countries, operated by the NOAA? Why had the fisherfolk not been relocated to safer places? Why were natural barriers such as forests/ mangroves being systematically destroyed along India’s coastlines? There were, thus, clear indications that a range of experts held the Indian nation-state, at least to some extent, responsible for abdicating its responsibilities towards its most vulnerable communities. The scale of devastation in 2004 could certainly have been mitigated with a more pro-active state/ more pro-people policies. What is equally important to underline is that in the Chennai floods of 20015 or through the Covid pandemic, very similar patterns of state and nation-level responses were to be repeated. But over and above the specific political configurations of Tamil Nadu/ India, I would to like to draw attention to a short but deeply poignant piece by Sumanta Banerjee, “Reflections on the Tsunami,” EPW, Vol 40. 2 (Jan 8, 2005) :97-98. Banerjee points out that whenever there is a natural calamity – whether an earthquake (e g, in Bhuj in 2001), or a cyclone (e g, in Orissa in 1999) – or industrial accidents like the Bhopal disaster in 1984, the unsuitability and inefficiency of the existing infrastructure to cope with their after-effects get exposed in all their horrid manifestations. But underlying the insensitivity/ carelessness of particular government agencies is a larger ‘organisation of the economy and political arrangements’ in which the poor have played no part. Quoting the scientist Robert Oppenheimer, Banerjee reminds us that neither of these, (economy or politics), derives from, nor is in any tight way related to, the sciences, because, although the growth of knowledge is largely responsive to human needs, it is not fully so. Thus even when science and technology are responsive to human needs, the ‘organisation of the economy and political arrangements’ often stand in the way of their proper utilisation. These humanitarian concerns are absent, Banerjee proposes, in the Indian government’s policies of disaster management too.

- Partha Chatterjee, “Subaltern Studies and Capital,” EPW, vol. XLVIII.37 (Sept. 14. 2013) :69-75

- Partha Chatterjee, The Politics of the Governed: Reflections on Popular Politics in Most of the World, NY: Columbia UP, 2004

- This subject is, similarly, too deep to go into here in detail. Among the most important thinkers on the subject are undoubtedly V. Geetha and S. V. Rajadurai. From among their many writings on caste-politics in Tamil Nadu see, Towards A Non- Brahmin Millennium: From Iyothee Thass to Periyar, Bhatkal & Sen, 1998. Another very important scholarly voice on the subject is MSS Pandian. See especially his Brahmin and Non-Brahmin: Genealogies of the Tamil Political Present, Permanent Black, 2006. [In fact in the documentary, Dr Revathi poignantly reminds us that even in the horrific aftermath of the tsunami, dalit laborers were being thrown out of their homes and/or left out of the government relief measures]. In general, political scientists have identified the decades of the 1980s/1990s as key moments of dalit/lower-caste mobilisation in post-Independent India. The new majoritarian ‘Hindutva’ politics since the 1990s is largely seen as a pushback of upper-caste hegemony against this democratizing initiative. While Eswaran’s documentary notes the caste-politics of the fisher-community in passing, scholars like Pandian have studied in detail how the ‘radical’ anti-caste edge of politics, even of parties such as the DMK, gradually began to hollow out with the nation’s new ‘liberalization’ agenda.

- Many such initiatives have sprung up in TN too: activists such as T.M.Krishna, attempting to take classical music to subaltern social spaces or projects such as ‘Science of the Seas’ curated by activists such as Nityanand Jayaraman, that foreground subaltern science and their understanding of Nature. Eswaran also uses classical instruments in framing the fisher-town to create a sonic space where caste and class-divide may similarly be questioned.

- Ranabir Samaddar, A Pandemic and the Politics of Life . ND & Kolkata: Women Unlimited, 2021.See also in this context Arundhati Roy, ‘The pandemic is a portal’ Financial Times, April 3, 2020 as well as her essay, “After the lockdown, we need a reckoning,” Financial Times, May 24 2020.

- This must remain as a footnote for now. But to indicate the general thrust of my argument, of the urgency of this question for the global South in an increasingly disaster-prone world, two books come immediately to mind: Amitav Ghosh, The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 2021 and Dipesh Chakraborty, The Climate of History in a Planetary Age, Illinois: University of Chicago.

REFERENCES

Banerjee, Sumanta. 2005. “Reflections on the Tsunami,” EPW, Vol 40. 2 (January 8): 97-98.

Chakraborty, Dipesh. The Climate of History in a Planetary Age, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

Chatterjee, Partha. 1986. Nationalist Thought and the Colonial World: A Derivative Discourse? Delhi: OUP.

—. 2004. The Politics of the Governed: Reflections on Popular Politics in Most of the World, NY: Columbia UP.

—. 2013. “Subaltern Studies and Capital,” EPW, vol. XLVIII.37 (September 14, 2013) :69-75

—. 2020. I am the People: Reflections on Popular Sovereignty Today, ND: Permanent Black,.

Chatterjee, Shoma. 2015. Filming Reality: The Independent Documentary Movement in India, ND: Sage Publications, 2015.

Harari, Yuval Noah. 2020. “The world after coronavirus,” Financial Times, March 20, 2020.

Geetha, V. and S. V. Rajadurai. 1998. Towards A Non- Brahmin Millennium: From Iyothee Thass to Periyar, Bhatkal & Sen.

Ghosh, Amitav. 2021. The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

Kapur, Geeta. 2022. “A Critical Conjuncture un India : Art into Documentary, in Rashmi Devi Sawhney ed, The Vanishing Point: Moving Image After Video, ND: Tulika Books: 120-141

Khanna, Ranjana. 2003. Dark Continents :Psychoanalysis and Colonialism, Duke, NC: Duke Univ Press.

Mulvey, Laura. 2011. Death 24x a Second: Stillness and the Moving Image, London: Reaktion Books.

Pandian, MSS. 2006. Brahmin and Non-Brahmin: Genealogies of the Tamil Political Present, Permanent Black.

Rose, Jacqueline , 2020, “To Die One’s Own Death,” London Review of Books, (19 November, 2020) 1-10.

Roy, Arundhati. 2020 ‘The pandemic is a portal’ Financial Times, April 3, 2020.

—. 2020. “After the lockdown, we need a reckoning,” Financial Times, May 24, 2020.

Samaddar, Ranabir, 2021. A Pandemic and the Politics of Life, Kolkata: Women Unlimited.

Snowden, Frank M.. 2020. Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present, Camb, Mass: Yale Univ Press, 2020.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. 2005. Death of a Discipline, Columbia Univ Press.

Sutoris, Peter. 2016. Visions of Development: Films Division of India and the Imagination of Progress, 1948-75, Oxford: OUP.

Vohra, Paromita. 2022. “Who is the First Person: On Making Documentaries”, in Rashmi Devi Sawhney ed, The Vanishing Point: Moving Image After Video, ND: Tulika Books: 175-187

FILMOGRPHY

RV Ramani, 2011. dir, My Camera and Tsunami

BIO-NOTE

Ajanta Sircar is Professor, Department of English, School of Social Sciences and Languages, Vellore Institute of Technology, Vellore. She completed her PhD from the University of East Anglia, Norwich, (1993-97). Her dissertation supervisor was Prof. Laura Mulvey. She is the author of two books: Framing the Nation: Languages of ‘Modernity’ in India, Seagull Books UK in association with Chicago Univ. Press, January 2011 and The Category of Children’s Cinema in India, published by IIAS, Shimla, Oct. 2016, released as part of their “Golden Jubilee Series.” She is also the co-editor of the recently released volume, Contagion Narratives of the Global South, Routledge, Dec, 2022.