The Politics of ‘Apolitical’ Films

In a neoliberal world, where cultural industries appropriate emotions and affective spaces, it would be unrealistic to expect popular mainstream films to portray social reality or to invite critical deliberations through cultural texts. Yet we often encounter such films, sometimes as regional language films like Jai Bhim, sometimes as independent films (Eeb. Allay. Ooh) from unexpected corners of the country. Popular cinema, even when the theme is a socially relevant one, or is based on a biographical account of a social reformer or a leader, prefers to play it safe, and stay away from ideological spheres, and instead offer an immersive experience of the visual opulence that digital technologies are capable of offering in contemporary times. A film that has successfully evaded the possibility of being a cultural text capable of portraying the life of sex workers, the multifarious dimensions of such a job within the social environment and in personal lives, is the film Gangubai Kathiawadi (2022), directed by Sanjay Leela Bhansali.

The film, Gangubai Kathiawadi, is loosely built around a chapter titled “The Matriarch of Kamathipura”, chronicling the life of Ganguhai in the book Mafia Queens of Mumbai by S Hussain Zaidi and Jane Borges. Gangubai Harjeevandas Kathiawadi was from Gujarat and became a brothel owner in Kamathipura during the early 1950s and 60s. She emerged as a leader and remained influential, and her interventions to ensure the welfare of the sex workers in Kamathipura were successful to the extent that she managed to meet the then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and discuss the issues faced by sex workers.

Though she is known to have sold drugs and illicit liquor and was assisted by a mafia king of the times, the film has a Gangubai who is a benevolent leader with a charisma that turns even her rivals into her admirers, as in the case of the transperson, Razia. The film is a biographical melodrama which is built on humongous proportions. Though it is a story of survival, every scene is staged, and even the faded walls and peeling plaster increase this sense of unrealistic dramatic moments.

Realism is kept stoically away from every scene, and every aspect of the film enhances this theatricality.

A tapestry of colour and music overwhelms the narrative, which is a romanticised and sophisticated yet tragic tale of a woman who fights to survive in the darkest moment in her life.

Art, especially in the modernist age, has been accused of foregrounding formalistic devices and hence lacks depth and aesthetics in its totality. This criticism was levelled even as the form was a reflection of the reality of existence, the fragmentation and alienation that defined those inter-war years in Europe. But in contemporary times, films by makers like Bhansali employ the form to divert attention from content, thereby building shallow cinematic spaces with minimal interventions by the artist in the socio-political sphere. So Gangubai fully disregards its ideological dimension and opts for visual opulence.

With a sex worker who was capable of asserting her voice as the protagonist, the film had the potential to drive home the reality of the life of exploitation and marginalisation. It is set in the red-light area of Kamathipura, with its squalor, violence and resultant social evils. But the director chose to romanticise the space, erasing its identity in visuals perfectly captured like a painting. The sexual violence experienced by the sex workers is sanitised throughout the film. The skilful use of greys and whites amidst the loud, garish colours and glitter of the slum has succeeded in eluding any constructive discussion around the reality of sex work and the deplorable condition of women and children subjected to a life of deprivation.

Gangubai is a film structured on a canvas that is larger than life. Every scene is carefully choreographed to erase the painful legacy of the story of Gangubai. Her identity from within her Spatio-temporal space is made irrelevant as the film hails you to observe the aesthetics of abundance, even when it is the grey tones used throughout the film. Gangubai’s white saree is not the white that should have been the colour of resistance – it is, as she, the protagonist, says in the film – one of the white shades, of motherhood, of a popular leader, the various whites in the film wishes to focus upon throughout the film, the whites that will not articulate the apolitical identity of any kind.

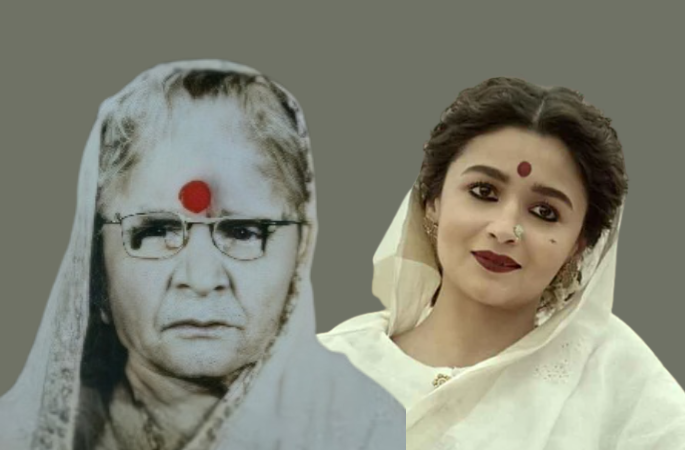

Gangubai’s pictures show her to be an ordinary-looking woman who exhibited grit and determination, but the film has Alia Bhatt depicted as charismatic, her authority established through the massive display of affection and acceptance of her authority and power. Her deep red lips and the heavy make-up accentuate the idea of the spectacle, the unreal world that she dwells in, unlike the Gangubai who lived through hardships that defined her identity.

The viewer is reminded of populist powers who stage rallies and deliver speeches to awe-struck audiences, carefully erasing the politics of public spheres and political deliberations.

The film succeeds in foregrounding the aesthetics and the formalistic possibilities even as every scene is built, structuring the narrative devoid of the political implications of gender. Deliberately kept within the neoliberal ideological vacuum, even though the film is based on the biography of a sex worker who rose to be the spokesperson of the women who lived their whole lives oppressed, exploited and marginalised as sex workers in the 1960s and 70s. If there is a message to deliver, it assumes a reductive tone, even a regressive one, that fixes the blame on young girls and their choices. In a poignant scene where one of the girls asks Gangubai to write a letter to her father, we are informed that the girls share a similar history. They express sentiments of guilt and regret over having left their homes on their own volition. While the reality is complex and difficult to grasp as a social reality, the film adopts a problematic position. Later in the film, Gangubai calls home to realise that her father had died, refusing to forgive her even on his deathbed. The sense of shame and repentance defines her as she attempts to ignore those unpleasant emotions through indulgence in alcohol.

Gangubai, undoubtedly is a visual treat, exploiting the possibilities of the medium to the utmost. But it fails to explore the opportunities the narrative has to offer, the director toeing the line of neoliberal normative patterns by refusing to investigate the disturbing social environment, the context within which the character of Gangubhai struggled, survived and emerged as a leader. The emptiness of the narrative is striking as we watch the protagonist speak to the crowd, to the prime minister, for they sound shallow and hollow, without any scene establishing the reality of sex work, the disturbing ecosystem of Kamathipura, without the stench of people living in tiny cubicles, the depravity that such toxic environments are capable of festering and the innumerable women who remain victims of systemic violence.