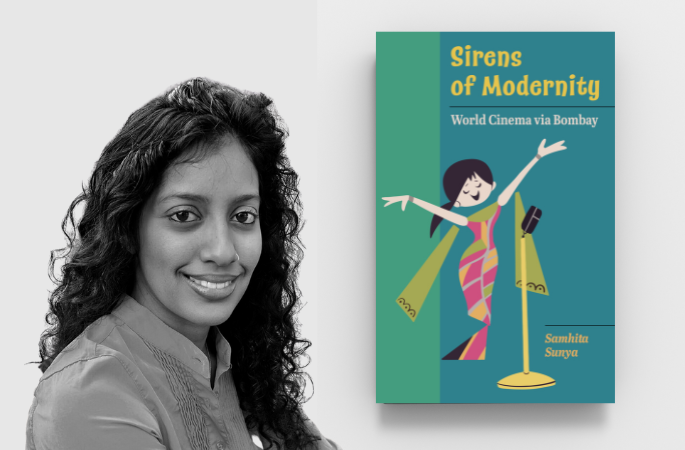

Author: Samhita Sunya

The University of California Press, 2022

akira kurosawa vittorio de sica, wyler hitchcock wajda, mizoguchi de palma, wyler hitchcock wajda, brian de palma! akira kurosawa vittorio de sica . . .

—Chintu Ji (Ranjit Kapoor, 2009)

Thus begins Prof. Samhita Sunya’s magisterial book, profound labour of love, with the lyrics of a song from a film, which informs us of the cinephilia and popular Hindi cinema’s double pull of being submissive/paranoid and transgressive/schizoid in a Deleuzian sense––an homage to the great masters of cinema, “a parody of the item number,” while simultaneously making pun/fun of their names as befitting a nonsensical rhyme, fitting the ‘meter’ of a Hindi cinema song where lyrics have to be tailored to the tune. Nonetheless, Sunya makes a strong case and argues creatively and convincingly regarding the erasure of the robust travel of Hindi films in alternative routes to the film festivals that had a predilection for art cinema and was driven by the privileging of elites and their investment in catering to the Eurocentric needs regarding subtle and nuanced Orientalism. Infact, Sunya successfully recovers the many complex routes internationally, particularly during the Cold War, nationally through which Hindi films were made and travelled and fills a long-felt void in Indian cinema studies. Additionally, the gift of the book is Sunya’s language, which has disallowed the disciplinary parlance and dryness to overwhelm the poetry and poignancy of the author as a film studies scholar of rare acumen.

Additionally, Sunya is a unique scholar who works across borders, particularly through the travel of Indian films and the concomitant (international) production and reception circuits, and spectrums, as well as a unique researcher who undergirds her scholarship in the discourses surrounding stardom, caste, social justice, inclusivity, and equity. More importantly, through the borderless appeal of songs and dances. While scholars have focused on countries like Russia or those in the middle east or Turkey regarding the popularity of Hindi cinema songs, Sunya’s book is singular in foregrounding the appeal of Indian songs and dances and narratives revolving around love and loss across borders. Indeed, Sirens of Modernity engages with “public debates over gender, excess, cinephilia, and the world via Bombay—or more specifically, via a set of Bombay films, film songs, and love lyrics over a ‘long’ 1960s period, bookended by the 1955 Bandung Afro-Asian Conference and 1975 Indian Emergency” in a sustained way to trace the route to World cinema via Bombay films, in particular through its sirens of modernity. I want to briefly discuss her book to give an idea regarding the clarity of its objective and the organisation of chapters.

Sirens of Modernity: World Cinema via Bombay

In her efforts to inform us of the transnational community of cinephiles united by their love for the excess of Indian/Hindi popular cinema, predicated on colourful love/romance and the jazziness of song and dance, and melodrama and comedy, Sunya focuses on the centrality of the siren, as indicated by the title, as encompassed by the alarming but seductive figure of the female singer-dancer figure to the melodramatic narrative and its consumption across borders/ languages/culture. The intervention of the book lies in its challenging the exclusion of mainstream or popular Indian cinema and restricting the world-making of Indian cinema to the film festival circuit, often narrowing it further down to the films of Satyajit Ray. While Indian cinema scholars have pointed to such a grave exclusion, Sirens of Modernity: World Cinema via Bombay provides us with the material proof of the circulation of popular Hindi films inside and outside India across borders through remakes and coproductions, and collaborations. Sunya focuses on the challenges of translation through subtitles and their omission in song sequences and the specificity of culture, for instance, the entrenchment and the tentacles of caste, which renders marriage impossible with members outside its fold, as instanced by Sakharam’s confession to Afanasy while sympathising with the hurdle in his love across borders. Such a specific trait, symbolising discrimination and social injustice, resonates, however, universally because of prejudice, racial hatred, and inequity due to class, although the degree of oppression and suffering inflicted are incommensurable. While Pardesi/Khozhdenie was produced in Hindi as well as Russian, thus overcoming the problems of literal translation, those regarding culture had to be faced. But such challenges offered opportunities. More significantly, “Pardesi/Khozhdenie’s exaltation of friendship unfolds through its opposition of idealised platonic homosocial love to both romantic fulfilment and commercial success. Aside from the heterosexual presumption of this opposition’s denial of any possibility of sexual desire between men, feminine figures like Indira, Champa, and Lakshmi (whose name invokes the Hindu goddess of wealth) appear as siren-like temptations—even if naively so, on their part—that offer opportunities for both erotic pleasure and material gain” (111).

Therefore, what was generally disavowed and erased in mainstream Indian cinema of the long 1960s finds a place in the Indo-Russian coproduction Pardesi/Khozhdenie, when an Indian character (Sakharam) openly acknowledges his love across caste and confesses to the suicide of his female lover. It is topical because of the ubiquitous honour killings among the Indian community, where the young lovers are violently punished by their own parents and close relatives for transgressing caste, often trying to hide their inhumanity by reporting murder as a suicide. Of such import is Sunya’s study of the significance of the world-making through and by Indian popular cinema, which, while entertaining us with its colourful heterosexual romance and the homosocial bonding between the two male protagonists, who foreground productive cooperation and collaboration and question and critique exploitation and colonisation, also gives us an insight into the heart of darkness of a culture embedded in caste. Thus one could argue that Sunya’s painstaking efforts to recover the alternative routes of the travel of Indian popular cinema in its worlding or world-making impetus to unite hearts through their love for cinema is equally if not even more relevant than the travel of the Indian art cinema canon through the generally elitist film festival circuit where the cinephilia is restricted to specific authors and the aura surrounding their works. While “the figure of the singing dancer-actress emerged as metonymic for Hindi cinema’s ostensibly immanent expressivity, legibility, and exchangeability, partly because several star actresses—particularly dancer-actresses—were well known for working across multiple languages and commercial industries within India” (14).

Sunya compares and contrasts Pardesi (1957), which was an Indo-Soviet coproduction directed by K.A. Abbas, the progressive writer associated with the Indian People’s Theater Association who was invested in social realism, with Singapore (1960), an Indo-Malay collaboration, with regular commercial production houses, F.C. Mehra’s Eagle Films of India with the iconic Shaw Studios and Cathy Kris of Singapore, trying to cater to the needs of the market. The author recovers rare primary and secondary materials from the archives across borders to foreground the cinephilia and demand for the popular Hindi films that dictated the targeting of the embedded spectator in the text through idioms specific to Indian cinema both in the ideology-driven Abbas’s work and entertainment-driven Singapore, directed by the popular cinema icon Shakthi Samantha. Padmini, the lead actress in Singapore, also is iconic of the siren––the star from the south who could dance and be voluptuous simultaneously, her Otherness rendering her the heroine/seducer/siren:

“The seemingly insatiable demand for Hindi films repeatedly bore the consternation of editorials and official reports from both within and outside India that painted the commercial song-dance films as siren-like: alarmingly noisy and nonsensical, if not dangerously seductive and utterly vulgar. Repeatedly, Hindi films in this period rendered the figure of the singing dancer-actress a metonymic for the singing, dancing cinema. Through reflexive allegories, they defensively extolled not cinema per se but, more specifically, the love that Hindi cinema could engender en masse in the form of cinephilia” (14).

Sunya extends the cinephilia to lyrics from singing and dancing in her painstaking and pathbreaking chapter on “Prem Nagar” or the “City of Love” as a genealogy of the lyrical trope. Indeed, “Moving Toward the ‘City of Love’: Hindustani Lyrical Genealogies” is the first of its kind to painstakingly engage with lyrics that are so central to the love of Indian cinema with such detail and depth. Indian cinema teachers would know that lyrics have been engaged only sporadically by scholars, particularly in the context of the films of Guru Dutt or the films of “Islamicate” cinema, like Mughal-e-Azam, which has been engaged with in-depth by scholars like Ira Bhaskar and Richard Allen (2009). Sunya again fills a necessary and long-felt void through her perceptive research and persevering archival work. It is also heartening to note the recent book by Usha Iyer on dance, Dancing Women: Choreographing Corporeal Histories of Hindi Cinema (2020), which fills a similar void regarding the centrality of dance in Hindi cinema.

Sunya’s intervention is in reading the window not just as a frame but as cinema, focusing on Padosan’s unique soundscape and contrasting it with that of Dastak (1970), a marker of the Indian new wave cinema. More importantly, for my preoccupation with Tamil cinema, Sunya details the saturation in returns, necessitating the expansion of the market and the reason for Tamil cinema directors like C.V. Sridhar (Pyar Kiye Jaa/Carry on Loving, 1966)) and S.S. Vasan (Teen Bahuraniyaan/ Three dear daughters-in-law, 1968)), a remake of K. Balachander’s Tamil film Bama Vijayam (Bama’s Visit, 1967) as well as its Telugu version Bhale Kodallu (1968), which were produced by Madras-based Gemini Pictures, to venture into Hindi cinema/versions. The efficiency of the Madras Studio economy could be discerned from (the recycling of) the three main actresses who worked in Tamil, Telugu, and Hindi versions. Nonetheless, Mehmood’s stardom in Hindi cinema after Padosan led to the caricaturing of the Madrasi, who cannot speak Hindi/English without a pronounced accent, which continues in Hindi cinema until today without a break. For instance, the many roles played by Johnny Lever as a Madrasi/South Indian, particularly in the 1990s, with an accent were a continuity of the trope. Ironically, Mehmood drew from Tamil/Telugu originals for much of his films. But, of course, the period Sunya engages in was an earlier one, before Mehmood’s melodramatic engagement and indulgences with Tamil cinema in particular, as exemplified by the various actresses, including Padmini, Bharathi, and the iconic Manorama, the incomparable comedienne, who had to bear witness to his misogyny and ridicule.

After her remarkable insights on the “Comedic Crossovers” from the south to the north, Sunya sets her lens in the subsequent chapter on “Foreign Exchanges” through the “Transregional Trafficking” in Subah-O-Sham (Persian/Hindi,1972), based in Teheran. This chapter again is a tour de force in its engagement with the materiality and vagaries of foreign exchange, emblematised by the “celluloid bangles,” predicated on an economy of smuggling due to the heavy import tax, and the “interchangeability between celluloid and plastic” come to the fore in her chapter on the Indo-Iranian coproduction, Subha-O-Sham/Homa-ye Sa’adat (From Dawn to Dusk,1972) which astutely traces the trajectory of world cinema via Bombay through travel and the histories of the passage of commodities and the business surrounding them.

Prof. Samhita Sunya’s book thus is a committed and passionate look at the travel of the many diverse and illustrious films from Indian/Hindi/Tamil/Telugu cinema at the material level of the lived reality of box office and audience engagement with song and dances being their soul, which was performed by/associated with the wonderful body of the sirens, simultaneously sacred and seductive, thus entrenching and challenging patriarchy and its diktats regarding caste, class, and gender. Sirens of Modernity: World Cinema via Bombay is a welcome edition as it fills a void and sheds light on the universal appeal of Hindi cinema and proves through its rigorous archival research across borders and rare primary materials (reproduced/illustrated with beautiful pictures in the book) that the worlding of Indian cinema is not new. Sunya’s book will significantly help the many faculty, students, and researchers invested in film and cultural studies, apart from the vast swath of scholars studying the transit and impact and the highly intricate network of movement of cultural goods/artefacts. Sunya’s book is a gift to faculty and students of both undergraduate and graduate studies because of its depth, lucidity, and accessibility.