The immigrant American knows all too well the pain of losing family. Not necessarily to death, but inevitably to the isolating constraints of distance.

When I was five years old, I left behind a clan of cousins, aunts, uncles, and grandparents in the Philippines for a life of more excellent opportunities in the United States. Little did I know how heavy this cost would weigh on me as I grew older.

Two oversized bags of luggage in tow, my parents brought my sister and me to Lexington, Kentucky, a city as mundane as Manila is chaotic. As soon as we landed on American soil, the gears were in motion for my parents to pursue the “American dream.” My mother laboured tirelessly at the local hospital as an ER nurse while my father enlisted in the US Army as a medic.

In just a few years, their hard work paid off, and we were able to move out of our cramped apartment and into a good two-story house in the suburbs. There was a porch, a spacious lawn, and a fence for privacy, practically an immigrant’s dream.

My parents’ growing success did not keep them from communicating with family in the homeland. Late at night, accounting for the 12-hour time difference, my father would speak with my ageing grandfather on the phone. I called him Lolo Mars – lolo meaning grandpa in Tagalog – and I knew little about him.

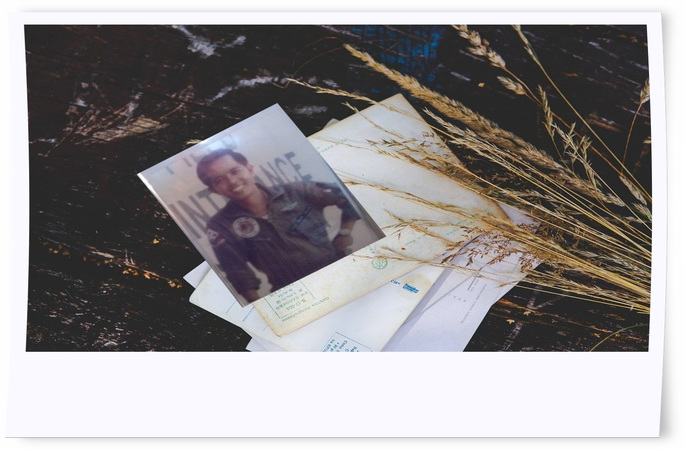

In the Philippines, my family had lived in Lolo’s house because my parents couldn’t afford their own. From tidbits I’d overheard from my parents, I knew Lolo used to be a pilot like my father was in the Philippines. Due to his work, Colonel Calub was rarely at home, and when he was, he was known to be a disciplinarian.

Allegedly, Lolo was the first person ever to make me cry. I remember slightly more about my grandmother, Lola Lily, who was a warm soul, taught me how to dip pandesal in coffee, and often spent time with my cousins and me.

Having left the Philippines so young, these are memories which I can only vaguely remember.

After immigrating to the US and before I reached adulthood, my family only made one trip back to the Philippines. Although financially more secure than ever before, my parents were scrupulous with their savings and were hesitant to spend the exorbitant amount of money needed for a trip to the Philippines.

A round-trip ticket for one person cost over a thousand dollars, and we were a family of four. But the time came when my father felt compelled to return to his hometown and pay respects to Lola Lily, who had died a couple of years before.

Thus, in 2010, I made my first ‘homecoming.’

We spent Christmas with my father’s family. Old characters reappeared, like cameos of favourites from seasons past: Lolo Mars, Tito James, Tita Annabelle, my cousins Paul, Philip, and Pauline… the list could go on.

Upon seeing their faces, there was an instant familiarity – but at the same time, a disconnect. As I opened my mouth to speak in my native tongue, I realised that the words no longer formed as naturally as when I had left. Too embarrassed to talk in broken Tagalog, yet unwilling to come off as pretentious by speaking English, I stayed silent.

Quickly, I realised that there was a gap between me and my relatives, a chasm deepened by cultural, linguistic, and value differences. One that seemed untraversable.

When I returned to the states, I felt discouraged from engaging in my Filipino heritage. Being in the country my parents called home and not feeling the same sentiment was perturbing, and I already felt like I was neither Filipino enough nor American enough – but that’s a separate discussion.

As the new year began, my American life resumed like clockwork, and I went about my days with hardly a thought about my relatives in the Philippines.

Years passed, I grew up from a shy kid into a headstrong teenager, and the nights of hearing phone calls in Tagalog were few and far between.

On the day I received my college acceptance from my first-choice school, (which I was unable to attend due to inadequate financial aid), my father received a call. It was from Uncle Jet, his younger brother, explaining that Lolo Mars had passed away. He was in his seventies and had long been suffering from health issues. One night, Lolo succumbed to a stroke, passing away in his sleep.

My parents were shell shocked, and all attention immediately shifted away from my achievement. For a moment, I felt selfish. There I was, acceptance letter in hand and something just had to rain on my parade. But even through my cloud of vanity, I recognised the gravity of the situation. As my parents wept, I retreated to my bedroom and wrangled with my tumultuous emotions.

As much as I wanted to muster up the grief, I couldn’t shed a tear for my own grandfather. I did not know the man. Our conversations were always short and routine, always starting with kamusta po and ending with ingat. As I replayed fragments of memories searching for a sign of real connection, I conjured nothing of consequence.

At last, I was able to grieve, but not for the person my grandfather was. I mourned the person I could have known, grown up with, sought guidance from. I mourned the lolo he could have been to me. I lamented the fact that what I knew of him amounted to breadcrumbs, and now his life could only be recounted by secondary sources. How many adventures could he have regaled me with, only for them to be burned up with my grandfather’s body and never told?

In a way, much different from my parents, I grieved the loss of my grandfather.

In truth, we probably wouldn’t have gotten along due to his traditional and strictly Catholic convictions. If we were able to get to know each other, I feel as if I would have disappointed him in many ways, and certainly for my social and political views.

Nevertheless, I would have rather had a bad connection with a grandfather I truly knew than a superficial relationship with a stranger related by blood.

To be clear, I am immensely grateful for my parents’ sacrifices and the leaps and bounds they took in order to secure the comfortable life my sister, and I enjoy today as American citizens.

But I cannot help but yearn for the richness of a close-knit intergenerational family, one that I and many other isolated immigrant children, will never have.