Home (2021) As A Representation of Homes In Neoliberal India

Kerala saw the release of a film, Home, in August 2021, through the OTT platform Amazon Prime. The film attempted to unravel the intricate relationship dynamics in a home in contemporary India, where humans live dual lives in the physical and virtual spaces, negotiating with emotions and desires, characteristic of a neoliberal social order.

In an age where micro fascism thrives and authoritarianism rules undefeated, it is imperative to reflect upon the concept of home. Homes are the breeding grounds of micro fascist tendencies, as children are born and brought up within the controlled atmosphere of homes. If in earlier times, with larger families, living in extended families, offered children opportunities to make choices and grow up with relatively greater independence, the smaller nuclear families of contemporary times restrict such freedoms. Parents loom on the horizon for the children, who have limited choices, hence fewer life skills for their adult lives. Homes in the neoliberal world can raise children who fail at imbibing values of democracy; as they grow up in confined environs, where their parents’ fears put them under constant surveillance. And the neoliberal markets prod them to be individualistic and self-sufficient, with their identities as individual selves being of supreme importance. In such a world, relationships crumble, community solidarities become non-existent, except maybe at times of a crisis, which dissolve once the moment is over. Homes then become sites of conflict, instead of an interlinked entity, where individuals permit their identities to evolve in frequent communication with one’s family members. Homes are then occupied by strangers with inflated egos, forced to live in a single constricted space and quarrel incessantly. As they are psychologically wounded, the wounds permitting micro fascist tendencies to thrive, divisiveness and hatred growing in these crevices, as societies become anomic and dystopic.

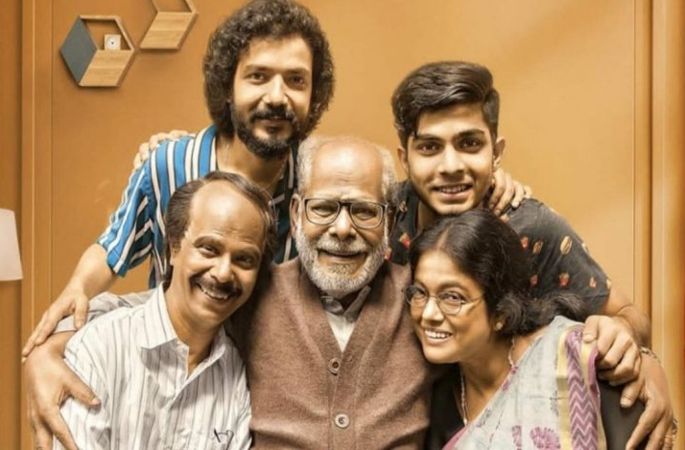

The Malayalam film Home released in August 2021, becomes relevant in this context. Directed by Rojin Thomas, the film is well-crafted and narrates the tale of a home with four people, a father, a mother and two adult sons. The father, Oliver Twist is an insignificant ‘ordinary’ person who has failed in his business and lives on the income of his wife, a retired nurse who takes care of an invalid father-in-law. The mother is always around but never loud enough to be heard, except when the father feels insulted by the son. The elder son, Antony, is an architect who chooses to be a filmmaker. He represents the scores of Malayalee youngsters who study professional courses and then decide to pursue their passions in various artistic domains. The younger son, Charlie, a compassionate student, is yet to grow up as an adult. The film progresses to tell the tale of the father-son relationship and the father’s struggles to find validation and recognition from the elder son, a successful filmmaker.

The film reflects upon the role reversal in parents and children as the kids grow up to be adults. What should a home represent where children have become adults?

What is expected of them? Should parents be wary of their adult children? Should parents be valued as per their functional roles as providers? The father in the film is repeatedly referred to as a failure. And the film narrates the tale of his growth in stature as a superhero, who had once saved a child’s life, who grew up to be ‘successful in life. Parents cannot always be superheroes, as the film depicts. They remain ordinary and plain; their ordinariness does not make them inconsequential in any way. Parents, in real life, remain as humans who struggle to deal with parenting and live within the normative structures of communities throughout their lives. Their negligible achievements and failures are more significant than life for young children. Still, as they grow older and their demands shaped by a commoditised cultural environment grow in stature, parents diminish into insignificant beings, incapable of rising to the expectations of children.

In the film Home, technology becomes the trope in this context. The father struggles with it and repeatedly fails, causing immense misery to the son, whose validation he persistently seeks throughout the film. Knowledge of technology makes Priya, his girlfriend’s father, respectable and admirable in the eyes of the young sons. Growing old is also about adapting oneself to change. It is about remaining vibrant and active, like the frail old father-in-law who consistently sits and types on a typewriter that has no ink. By the second half of the film, the protagonist learns this lesson of remaining proactive when he masters technology in the form of mobile phones.

Home is not just about children learning to respect their parents, as the film Home suggests. It is about every family member learning to adapt and adjust to change. Dependency will destroy homes, but interdependency will make them stay as a space of warmth and mutual respect. The film remains clear from such a reading of the concept of home. It gives a climactic twist and establishes the status quo in the parent-child relationship, with obedient children and parents who still exert control over their children. Can such families thrive for long in a neoliberal world? The highly regarded individualism of neoliberal times also questions familial interventions in an individual’s personal intimate relations.

The filmmaker here is confused as to his ideological position – even as he embraces neoliberal values, he critiques the son’s annoyance at his father’s intrusions into the son’s life, be it his conflicts with his girlfriend or his job as a filmmaker.

Even though the sons live on a separate floor, they are intricately tied to their parents living downstairs since sustenance is provided there. As the film ends, nostalgia drives the filmmaker to bring the adult sons back into their parents’ bedroom. Is this what he wanted in this film? Or is it about being self-reliant – as the father tries to be – visiting the psychologist and the Tai-chi sessions he participates in? While parents learn to be self-sufficient, sons go back to being sons in this ‘Home’ – obedient and loving and respectful.

Disciplinarity of the contemporary world also shapes social relations, as in the case of the home in the film and the family members of diverse age groups. (Hardt and Negri, Biopolitical Production, 217).

The home in the Home, no doubt, becomes a typical home in a neoliberal society, where apolitical individuals survive through a “retreat into the self” (Pankaj Mishra, The Bland Fanatic, 108), into the fantasies offered by the simulacra, as the world around succumbs to fascist ideologies and discourses of hatred and Othering.

References

Mishra, Pankaj. The Bland Fanatics: Liberals, Race and Empire. NY: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2020.

Hardt, Michael and Antonio Negri. “Biopolitical Production,” in Biopolitics: A Reader. Eds. Timothy Campbell and Adam Sitze. Durham: Duke UP, 2013.

Endnote: Microfreedoms is a word taken from Pankaj Mishra, The Bland Fanatics: Liberals, Race and Empire.