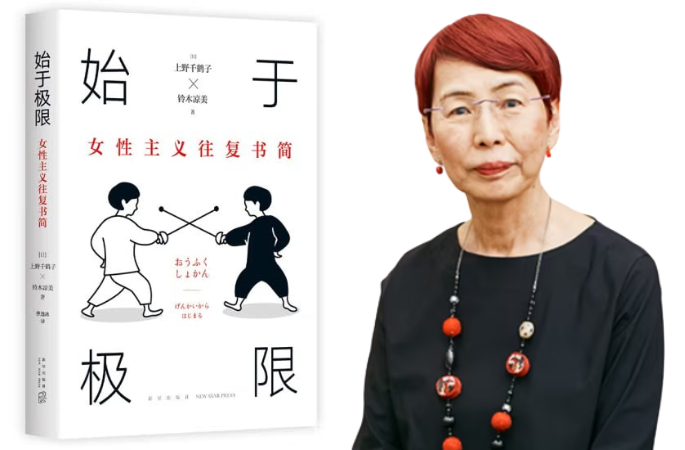

The book Letters Between Chizuko Ueno and Ryomi Suzuki, written by Chizuko and Ryomi, explores several contentious topics concerning modern feminism in Japan. This book consisted of twelve letters between Chizuko and Ryomi, which can be mainly divided into two parts — about women themselves and the social connection between women and other members. Part one includes the following topics: erotic capital, independence, and freedom, while part two deals with marriage, the mother-daughter relationship, and female friendship.

Chizuko, an eminent feminist and sociologist, has analysed the dilemmas that Japanese females have faced in her previous masterpieces, “Patriarchy and Capitalism” (1990) and “Misogyny” (2015), reflecting her values in relation to feminism. In this new book, she adopts a more holistic view to clarifying the feminist issue by communicating with popular writer Ryomi. Compared with Chizuko’s former books, which are more academic, this book is much more accessible to readers who have not gained a profound understanding of Japanese feminism.

Chizuko expressly responds to the confusion haunting Japanese females nowadays, especially those who struggle with entrenched patriarchy. The debate regarding erotic capital is the most complex part of Part 1. Some liberal feminists, like Ryomi, supportively claim that female sex workers with erotic capital are not the victims of patriarchy. Instead, sex workers revolt against Japanese social norms (i.e., females should be chaste for the benefit of their future husbands) with their “erotic capital.” However, Chizuko criticised the conception of “erotic capital,” first posited by sociologist Cathrine Hakim, by pointing out its paradox. For Chizuko, “capital” means something that can be gained and cultivated progressively. Theoretically, erotic capital solely refers to females’ physical appearances. Unlike cultural capital—academic qualifications and a business licence, or social capital— personal connections, physical capital might devalue during the ageing process, making it incompatible with the characteristics of “capital” itself.

Additionally, moving away from the male perspective as her lens, Chizuko uncovers the truth about the sex market. Her opinion is that the sex market is established on the overwhelming basis of gender inequality, undeniably dominated by males with more economic capital. As beneficiaries unaware of structural oppression between genders, Japanese men often defend that women voluntarily participate in the sex industry. Just as Chizuko states, “the greater the argumentation there is for self-decision, the greater the possibility there is to mask the structural oppression.”

Although the marriage rate in Japan has been declining these past few years, the majority of citizens still regard marriage as the most normal choice for females. Chizuko and Ryomi both mention that this is because marriage is conceived to be a guarantee of security and responsibility in Japan. For Chizuko, romantic love ideology, which is deeply ingrained in Japanese society, has also given females leverage over their choices, despite her reservations about the marriage system. As a former sex worker, Ryomi expresses her negative attitude towards marriage by witnessing that many men still purchase sex services even though they are married. What she advocates is that “girls-help-girls” communities are imperative to alleviate the anxiety about lack of security. This is not utopian, as Chizuko presents the idea that friendship between women can be long-lasting. Indeed, women can support each other emotionally. According to Chizuko, women’s relationships are invaluable because of their ability to enrich themselves.

As for the mother-daughter relationship, neither Chizuko nor Ryomi has clarified to what extent this kind of relationship could influence the development of a woman. However, Ryomi objectively depicts how she was bewildered by her mother’s contemptuous attitudes towards housewives and prostitutes in her youth. Ryomi then concedes that she has chosen to be a prostitute, driven by her mother’s weird attitudes. Chizuko instead focuses more on analysing the underlying reason behind it. No theory has been proposed to explain why a mother’s values could be so influential on her daughter. Therefore, whether the early mother-daughter relationship can consistently affect the subsequent choices of a daughter remains unknown. And do a daughter’s decisions always reflect her mother’s educational methods? More research should be done in this field.

To conclude, this book is powerful because it introduces different topics related to Japanese women in clear and straightforward language. Chizuko and Ryomi succeed in raising readers’ awareness of these feminist issues, by which readers are more easily able to understand the pre-existing predicaments Japanese women have been undergoing.