We will Progress, We will be Called Successful: The Question of Woman in Amar Jyoti

Introduction

Studies have pointed to how the vexed question of women’s oppression and ways of mitigating it largely through legal and social reform and the emancipation of women from rigid societal conventions such as child marriage, ill-treatment of widows, and lack of education had become the concern of the colonialists and social reformers (for instance, see Sarkar and Sarkar (Eds.) 2008). Studies have also pointed to how women’s equality as a political question came into being with increasing numbers of women joining the swadeshi movement led by Gandhi (for instance, see Patel, 1988). The early beneficiaries of colonial education, such as Babasaheb Ambedkar looked at women’s equality as part and parcel of the project of modernity; while on the other hand, the cultural nationalists supported women’s education to better stem the spread of western values thereby imagining women as repositories of traditional ‘Indian’ culture. In a widely accepted and much cited work (Chatterjee, 1989), the discourse of nationalism has been seen as ‘resolving’ the ‘women’s question’, by conceptualizing the nation as a political and cultural space, with women being custodians of the inner cultural domain.

Given that the first half of the twentieth century was a period of intense social churning and articulations of freedom from varied oppressors (and not always was the colonizer the oppressor) by different social groups, it is interesting to ask what it means for a woman to be free, and whether/how womanhood can be the ground for securing freedom. What would a trajectory that does not retrace that of anti-colonial nationalism look like for women? In other words, how would the articulation of the question of women’s freedom, autonomy, empowerment be, if it did not seek to be ‘resolved’ within the nationalist framework?

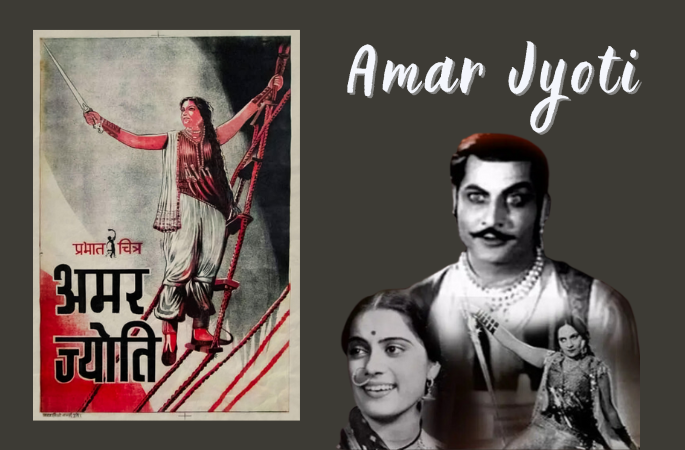

In this context, V Shantaram’s film Amar Jyoti (1936), the first Indian film ever to be screened abroad at the Venice Film Festival, is an interesting case study that imagines in nascent form a comradeship and lineage of women against what feminist discourse identifies as patriarchy. While there are articulations of freedom, given that the film works more like a costume drama/fantasy film, it does not locate itself either in its contemporary times, or in a well-known historical period, or in the epic or puranic mythical times. Even though it is a fantasy film, unmoored in time and space, it is not shorn of real concerns, and it is very much breathing the air of freedom of the times, though not necessarily of what became the hegemonic national kind.

Amar Jyoti tests the waters by asking – can women be a social group that fights for freedom? If we see such articulations of freedom as also incipient articulations of (another) nationalism/nation, the question is what geographical territory can form the basis of such autonomy. Since there is no land (both in the sense of place, and in the sense of terra firma) that their struggle can claim as theirs, it is the seas on which the struggle is mounted and from where their attack is launched by depleting the strength (of patriarchy) of the land. Does the attack remain an individualistic one? Are there signs of collectivization? What should the woman necessarily jettison in order to achieve emancipation? The present essay looks at how these questions are addressed in the film.

The Film in the Director’s Oeuvre and in its Times

- Shantaram strides over the history of Indian cinema like a colossus. Devoting 79 of his 89 years to cinema, he became an institution in himself, having produced 92 films, directed 55 and acted in 25. Born in the November of 1901, just five years after the advent of motion picture, V. Shantaram’s career spans across the history of cinema. He was of the firm belief that cinema could be used as an effective medium to expose and thereby change outmoded social mores. Amrit Manthan (1933) for instance, was a statement against religious obscurantism. Way ahead of his times, Shantaram made films that dealt with women’s issues. Kunku (1937) and Manoos (1939) were two Marathi films in which he told stories of child marriage in the former and love between a police officer and a sex worker in the latter. He may be seen as an early contributor to the making of the myths and dreams of an Indian nation-state. Shantaram’s films demonstrate the seriousness with which he plays the role of a social crusader. As a filmmaker, he possessed the power to participate in the construction of a ‘social’ in the nation-to-be-born. In this, he joined ranks with others involved in the process such as nationalists, social reformers and writers. His approach to character in the film is indisputably modern. For instance, the dialogues written for Saudamini, especially in her debate with Shekhar make for an early feminist discourse. (We will have occasion to return to this with detailed analysis later in this essay.)

It was not uncommon in the 1930s to make what has come to be called as ‘woman-centric’ films. Debates over women’s issues such as granting political rights and upliftment in the social domain constituted an integral part of the public discourses of this period of heightened political activity for India’s freedom. Films, by extension reflected such a zeitgeist. Even in the industry, women actors were known to have held far more power than they do at present. Women artists were known to have earned more than their male counterparts, something that is unheard of today. A number of women, including actors contributed regularly to the periodicals of that era and freely expressed their opinions on various matters with regard to the film industry. For instance, Sheila Devi Kumud, a social commentator writes in Filmland (February 7, 1931) that “heroes should be as befitting as heroines” even if they are not paid as highly as the heroines.2

From the beginning of cinema in India, women characters have played major roles, even if sometimes reactionary ones. Statistics reveal that the screen time for females actually declined over the years with the year 2017 demonstrating a mere 31.5 per cent, against the 68.5 per cent received by male actors.3 This may be attributed to the fact that early films were largely based on mythologicals which have always had meaty roles for women. Subsequently, one of the major modes of expression in Indian cinema was the melodrama. Family plots were central to the mode of melodrama thus making women significant parts of the films. Achhut Kanya and Jeevan Prabhat (Osten, 1936, 1937), Alam Ara (Irani, 1931), Chitralekha (Sharma, 1941), among others, are some of the films of that era with woman-centric themes.

Plot and Mise-en-scene

If we examine Amar Jyoti for what it basically is, that is, narrative cinema, then we must necessarily look at the way it takes up the above-mentioned questions relating to woman within the framework of narrative cinema whose main components are story, plot, character, time, space, and point-of-view. Garga calls Amar Jyoti “an allegory in the garb of a high-sea adventure in which Durga Khote plays the leader of rebel pirates” (2005:104). The plot revolves around Saudamini (Durga Khote) who is separated from her husband and denied custody of her child, Sudhir (Nandrekar). In order to extract revenge, she takes to the high seas as a pirate and is mentored by Shekhar (Narayan Kale). Declaring war on the state, and in particular its despotic minister of justice, Durjaya (Chandramohan), she launches her attack on the state and by extension, patriarchy. (The christening of the evil minister as Durjaya is interesting; Dur being the prefix for evil in Sanskrit.) When Saudamini attacks the royal ship, she captures Durjaya and unknowingly also Princess Nandini (Shanta Apte). Durjaya professes his love to Nandini but she has given her heart to a shepherd boy (Nandrekar) who in reality is Saudamini’s son, Sudhir. Durjaya and Sudhir collaborate to capture Saudamini. In the meanwhile, Saudamini has formed an alliance with Nandini to wage war against the tyrannical Queen as well as against victimization of women. Just when Nandini is about to declare her sentence against Sudhir, Saudamini appears to rescue him. Nandini and Sudhir are married and they, along with Shekhar’s daughter, Rekha (Vasanti) are to carry forward Saudamini’s legacy.

The film has an interesting mise-en-scène. The formal features of the film, such as the repeated scene of waves lashing the rocks, or the costumes of the female actors have pertinent symbolic values. Ever since he made the hugely successful Gopalkrishna (1929) with the bullock cart race as its highlight, Shantaram realized that every film should have that one scene audiences are drawn to. He was also the first filmmaker to make a colour film, Sairandhri (1933). He introduced the trolley shot for the first time in Indian cinema in his silent film, Chandrasena (1931). In Amrit Manthan, he was a pioneer in the use of the telephoto lens. The audiences were enamored by the screen filling up with the sinister-looking eye of the priest in the style of German Expressionism (as in Bunuel’s Un Chien Andalou), one of several influences on Shantaram.

In Amar Jyoti, clearly the shots of the ocean taken at Bombay Harbour and the Malvan coast, along with recreations in the studio, and the burning boat are stunning; even more so that they were made at a time when technology was at its budding stage. Apart from its visual appeal, this image has a strong metaphoric value. The first romantic scene of the film is shot in a stylised manner in which the couple is placed in a pastoral setting with trees, grass, a pond and a soundtrack filled with bird song. A mise-en-scène such as this went on to become a template of sorts for what came to be called, rather pejoratively, as Bollywood romance. Further, Princess Nandini breaks into song and the shepherd Sudhir plays the flute, the recall value of which places them undoubtedly in the realm of mythology. For the audience, the association of the cavorting couple makes them screen incarnations of the celestial lovers, Krishna and Radha. The interesting twist in the tale, however, is the filmmaker’s subversion of the apocryphal though well-known stories of Krishna’s mischief with the gopis. Here, it is Nandini who steals Sudhir’s clothes and he has to chase her around to retrieve them. The erotic element of the chase is enhanced through picturization of these scenes in water.

Further, looking at the mise-en-scène, it is not surprising that the film, apart from being seen as a narrative that interrogates the status of women, has often been categorized as, among other classifications, a costume drama (Diwakar, 2009, Majumdar, 2009). Here, we propose that costume extends beyond mere visual appeal; rather it becomes the bearer of ideological stances towards masculinity and femininity. Saudamini and Rekha’s (later Nandini’s too) costumes reflect the desire to disown what is marked feminine both in terms of visuality and identity. Considering Nandini’s acrobatics on the ship, the demands of comfort and mobility also necessitate the adoption of what is akin to male attire. The film opens with Saudamini in similar attire with a sword tucked in her waist and another one in her hand. Evidently, the establishing image of Saudamini is as a woman masquerading as male. Durga Khote plays the role with the confidence and panache that derives from her own standing in society, coming as she did from an upper caste and class. Her role as an action heroine is reflective of an alternative idea of femininity. As Majumdar points out, “Action-oriented female roles can be read as a performative space for trying out alternative femininities” (2009: 81).

The Theme of the ‘Castrating Mother’

The film’s theme can be traced through Saudamini’s transitions from an ‘adarsh naari, adarsh ma’ (ideal woman, ideal mother) to a pirate to a castrating mother figure. On the surface, it seems to suggest that a woman’s act of asserting an independent identity seems possible only when channelized through a criminal activity outside the law. (As an aside, we may mention that in Hindi cinema, the women playing roles of negative characters known as vamps are the ones who are assertive and show a semblance of individuality.) For this reason, it is a telling choice because a pirate is a figure that represents the marginalized in overseas commerce. Piracy, as an activity, is as ancient as the seas. Ever since the sea was harnessed to the purpose of commerce across geographical boundaries, the pirate has sought to insert himself (in this film however, the pirate is feminized) into the narrative of prosperity. Lurking outside the purview of legitimate business, the only avenue open to the pirate is crime. Similarly, in the dominant discourse of patriarchy, the woman can only insert herself in the narrative of the empowered by becoming ‘like a man.’ To that end, she must necessarily eschew so-called feminine qualities of tenderness and propensity to weep. From sartorial changes to an aggressive body language and commanding voice, Saudamini readies herself to disavow the feminine and embrace the masculine. What we see operating here is a play on the binary of masculinity and femininity. Nandini, who expresses love for Sudhir is compelled to surrender her love to follow Saudamini’s footsteps. It is interesting that when these ‘freedom fighters’ loot ships, they are not only after wealth, but also after potential recruits to their cause against patriarchy. Rekha, the little daughter of Saudamini’s guide/mentor/sounding board, Shekhar, too is tutored to imitate Saudamini in her mannerisms and behaviour to look and behave more like a man than a woman.

The costume that is more akin to male evidently exemplifies Butler’s notion of gender as performativity according to which behaviour is not a consequence of our being born male or female; rather it is iterative performance to establish ‘the truth’ of gender that constitutes femininity and masculinity. Nearly six decades before Butler, Joan Rivière had argued that womanliness is a masquerade that strives to keep a balance between the male and female norms of behaviour (Butler, 2005: 89). Nandini, in order to align her goals of freedom with those of Saudamini, must necessarily change sartorially to appear like a male. More significantly, for a while at least, she must also sacrifice her heterosexual love to forge solidarity with and assist Saudamini in her quest.

It is interesting to note that the women in the film belong to the aristocratic class. What may be the reason for such a set-up? Does this indicate that women, howsoever privileged they may be in terms of their class/caste backgrounds, still remain subjugated to the males in the family and community? At the same time, is it precisely because of their privileged backgrounds that they have the luxury of resistance? In a reversal of John Berger’s widely-cited statement in Ways of Seeing, “Men act; women appear,” Saudamini in the film acts and the men react, if not exactly appear. The Shekhar- Saudamini dialogues are important as debates on the nature of freedom, femininity and patriarchy. The dialogues written by K Narayan Kale are central to an understanding of the complex multiplicity of discourses at work in the film. Saudamini’s dialogues expose the confusions apparent in her own mind. She chides Shekhar for having ‘aurat jaisi nazuk khayale’ (delicate thoughts like those of a woman) thus revealing her understanding of womanhood. At the same time, she asks, ‘main badla kyun na lu’ (why shouldn’t I take revenge?); a thought that slots her into the mould of ‘the lady avengers’ (Maithili Rao in Gopalan, Vasudevan, 2000: 216). These contradictions are played out throughout the film in order to blunt what could turn out be an extreme form of radicalism. Thus, Saudamini must necessarily remind/assure herself as well as the audience that she is a wronged mother and her desire for revenge was born at the moment of her erasure from the fetishized narrative of motherhood. After the burning of the enemy ship, Saudamini breaks into song in which she smiles with a deep sense of fulfillment. The song has a line, ‘Dushman se badla paya hai’ (I have extracted revenge from the enemy). Further, her cutting off Durjaya’s leg may be read as a signifier of the act of castration, an act that fulfils the role of destabilizing the power and authority of the male and establishing Saudamini as the Freudian ‘castrating mother.’

The ejection of Saudamini from her essentialized role as mother is the point at which her rage and sense of loss transforms into aggression. Thus, it may seem like conscientisation can occur only at a cost. Even a progressive filmmaker like V. Shantaram had to succumb to the demands of the market and audience taste by the resurrection of Saudamini’s intrinsic womanly qualities. Saudamini’s longing for her son is shown in a scene in which she returns to her cabin to open a box out of which she fondly takes out her son’s dress and holds it to her face longingly. This shot is an attempt to undercut Saudamini’s fiery speech in the preceding scene about revenge, rebellion and her desire to start a movement to challenge patriarchy emblematised in the queen of Swarnadeep who is chided for not understanding a woman’s feelings despite being a woman herself.

The unrepresentability of an unrepentant mother forces the staging of Saudamini’s banishment as punishment for the woman who dared to mask her innate feminine attributes of caring and nurturing with an ersatz masculinity. At the same time, the crusader in Shantaram ends the film on a note of hope for women. Rekha, the young girl, mentored by Saudamini, says on the latter’s exit, “No, I must not cry as tears are signs of weakness.” It is on her little shoulders that the gun to use in the battle against patriarchy has been placed. The burning lamp that is the last image on screen before the credits begin to roll is that symbol of eternal hope for all who wish to rise against injustice in any form.

The Question of Woman’s Autonomy

‘Freedom’, ‘liberation’, ‘emancipation’, ‘empowerment’, ‘autonomy’ are terms in moral and political philosophy which, preceded by the possessive noun ‘woman’s’ have been much in use for the last 200 years or so in the Indian subcontinent, with each term becoming ascendant and circulating through different discourses5 at different points in time. While women’s freedom, women’s liberation, and women’s emancipation imply an existing constriction in the form of an oppressor/oppressive system (from which the freedom of expanse is sought), women’s autonomy implies the capacity for self-determination, self-governing or being independent; women’s empowerment implies the power bestowed or obtained to effect changes by the individual or social group.

Amar Jyoti through the verbal medium (in the sense that this is not presented in the form of visual narration) articulates the idea of freedom and the nature of oppression that woman is constricted by. The effects of empowerment (as opposed to a transient sense of victory achieved by an oppressed woman against an oppressor) in the film’s narrative is postponed to a not foreseeable future, with the act of effecting change being seen as, as long and arduous as the action of sea waves wearing down the rocks; thus the process of change is seen as immortal6 (rather eternal, in the sense of forever ongoing) and incremental, and not as a short-term gain, or what can be accomplished by one individual in a lifetime. However, what is visually presented and also extensively debated in the film is what can be considered as the question of woman’s autonomy. In the rest of the section, we discuss how the film helps in understanding these different but inter-related ideas of women’s freedom, empowerment and autonomy.

Right at the outset, immediately after the credit sequence, the visual of the waves crashing into the rocks appears on screen, followed by the song “Duniya zulmojafa ki karte rahna masmaar”7 (Go around destroying the cruelty and oppression of the world), which is the anthem of a group of those who are called pirates (samudri daku) by those on the side of the reigning political authority; but the so-called pirates see themselves as fighters for freedom. This freedom is not the one which is historically known as the ‘freedom struggle’ against the British, but is a more ontological one of not being in slavish subservience to any kind of authority. This idea of freedom is articulated by Saudamini when she deals with those who have been captured from the ship in which Princess Nandini was. When the captured oarsmen say they were merely servants and hence should be spared, Saudamini says contemptuously of their slavishness that they are merely dead souls in a living body, and she bids them henceforth to join her forces to fight for the cause of others’ freedom. When she turns to the women who call themselves dasis (servants) of the Princess, she mocks them saying that slavery and servitude is the motto of their life; since they think that slavery is the greatest goal and joy of life, for them freedom and self-reliance would be a form of punishment, which is what she metes out to them.

But what made Saudamini become a ‘freedom fighter’? From what form of slavery has she aspired for release? In her conversation with Shekhar she speaks of how she did not take on the role of a pirate without reason twelve years ago. At one point in time, she had aspired to be an ideal woman and ideal mother, and did not happily embrace this life of an outlaw. She asks Shekhar just because she is a woman, can she not aspire to be free. Should she continue to be a slave to the man named husband, and be considered his property? Should he have the rights over her body, her thoughts, and her being? Should she be no more than a voiceless doll? She is furious that the queen of Swarnadeep, despite being a woman herself sits on her throne and presides over and applauds all the atrocities being heaped upon women. And it was because of the queen’s unthinking stupidity that Saudamini had to bear the label of a villain. She also points out how as a woman, she has no right over her son whom she has borne, nurtured and nourished, and how her rights of being a mother are denied to her, for the son is considered a property that belongs to the father, as a result of which the queen had snatched away her son from her to hand him over to his father.

Later in a conversation with Princess Nandini she elaborates on how after marriage she realized that woman is no more than a slave to the man, her husband. This slavery is sanctioned by law, sanctified by scriptures, and endorsed by the political authority. She says she was embittered when she realized this, and therefore took it upon herself to remove this form of slavery. She warns Princess Nandini that even if she became a queen, she would not be able to escape this slavery: she would still have to be someone who merely complements her husband, not stand for herself; so, whatever he wishes, she has to make her own too; if she goes against his wish, she could get beaten up by him for that. Thus, despite being a queen, and having all the wealth in the world, as a wife, her condition would still be worse than that of a slave. When Nandini is frightened by the horrific picture being painted, Saudamini tells her that no matter how horrific it sounds, every word she has said is true; by ignoring it, the truth could not be wished away. She says she has taken it upon herself to mitigate this evil and in its place is creating a picture of a world where men and women are equal and free. She invites Nandini to be a part of this endeavour. Nandini agrees to join the struggle that will benefit all women. Saudamini warns her that this may entail fighting, killing, and even sacrificing oneself.

The project that Saudamini has taken upon herself is not one that can be achieved instantly. The idea of short-term gains over long term change is extensively debated by Saudamini and Shekhar. The repeated visual image of waves lashing against the rocks to depict Saudamini’s struggle crashing against the ossified views of society (Duniya ki mazboot patharon par thakrati rahungi – I will keep hitting against the tough rocks of this world) and also Shekhar’s words referring to this (Samudra ki lahere thakara rahi hai aur Khud hi chittara rahi hai – you are hitting against the rocks in the ocean and are injuring yourself in the process) point to the nature of the struggle both literally and metaphorically – lashing waves wearing down the rock of patriarchy, and their attack from the sea depleting the strength (of patriarchy) of the land, even while struggle takes a toll on the individual. In the end, the film leaves us with the image of a flame, a torch that symbolizes the struggle, and the need to carry it forward, though in a less turbulent way.

The idea of change over time, which we call here as empowerment (that is, having or securing the power to effect change), is thus presented to us through visual metaphors. When Saudamini, having conquered the ship with the princess in it, orders to set fire to the ship to kill Princess Nandini, as a way of avenging the injustice meted out to her by Nandini’s mother the queen, she rejoices at the sight of the ship set ablaze. She sees it as a sign of victory over her oppressor. But towards the end of the film, it is the lamp which becomes a visual metaphor to describe the life-work that Saudamini has taken upon herself – a lamp that burns bright and lights another lamp to keep the process of the struggle on-going. Thus, empowerment here would be not mere role reversal between victors and vanquished, not revenge against the oppressor, or revolution involving sudden seizure of power. It is instead seen as a perpetual struggle, with each struggle illuminating and paving the path for other struggles. Therefore, empowerment would not be a condition springing up all of a sudden in future, as much as a process unfolding over time, which is captured by the visual metaphor of the waves lashing against the rocks, themselves scattering and dissipating, but relentlessly wearing down the mighty rocks by their action.

As it emerges in the discussion between Saudamini and Shekhar, while Saudamini’s struggle against her perceptible oppressors like the husband and the queen are necessary, it is not seen as an end in itself; her desire to free herself from what she sees as slavishness is a necessary, but incomplete step in the larger work of wearing down ossified social and political systems. The price that she has to pay for living dangerously on the high seas of treason may be somewhat mitigated by her actions and of those who will follow her, which may cut the ground from under the feet of those who had been hitherto firmly planted on land.

While the film sets up the issue, and debates and discusses what we call here as ideas of woman’s freedom (in the sense of breaking away from an oppressor) and women’s empowerment, it is most interesting for presenting and visually narrating what can be called the life of an autonomous woman (one who is self-directed and self-determined). Saudamini has no family, religion or political dispensation to which she belongs or is answerable to. But she is not alone; she is with a crew on a ship that creates terror on the seas; so there are no relationships outside of the work that she does, and the idea of working for a family (or even, say, working for the country) does not arise. Shekhar, with whom she discusses questions of means and end, and Shekhar’s daughter Rekha, whom she is moulding in her image are two who are responsive to Saudamini’s tumultuous emotions; they are kindred souls ideologically and in spirit. But there is no question of private emotion or intimacy, precisely because those emotions smack of womanly weakness and male privilege (when Durjaya, even though lame and in chains, tells Saudamini that he as a man has every right to demand that a woman [in this case Nandini] love him, Saudamini sharply cuts him down by refusing to see him not only as a man, but also as a human).

While Saudamini rules the seas, on land she and her group live in caves, which is their hideout. The terms and conditions for their entry to the mainland, where they are considered as criminals are clear – they have to go in disguise, or be imprisoned as criminals. Her son too, brought up in the mainland would consider her a criminal, as there are no frames available yet to make intelligible and acceptable Saudamini’s actions; hence she cannot disclose her identity as his mother to him. Her attempt at re-inscribing the meaning of womanhood is too nascent, and Saudamini herself in the end is too full of doubts about what her actions amount to, and whether the larger cause she has fought for is sullied by her partisan motives as a mother.

Thus, woman’s autonomy here is presented as searching for new values and meanings for one’s self and life, for which existing society and social relations may not be hospitable. What would be the terms and conditions by which a new set of relations are forged? What is gained and what is lost in the transmigration of self from the old to the new? How does a woman who questions the basic premises of social organization around gendered division of labour and sexual hierarchy come to be seen as a threat, one who has to be ridiculed, tamed or banished as an outlaw? – Amar Jyoti’s narrative, through what seems like a fantasy setting, having no specific referent in terms of place and time is significant, for, in its own way, addressing these questions – questions that are important to date.

Notes

1 https://www.jstor.org/stable/24352438

2https://pkray.blog/2020/05/24/the-1930s-of-indian-cinema-and-gender-questions

3https://themitpost.com/women-indian-cinema-tale-representation

4 Shantaram was not new to censorship. His silent film of 1930, Swaraj Toran (Garland of Freedom) was subjected to heavy censoring. The film was a veiled allegory of victory over foreign rule. Finally, the film was released after several cuts and a change to the title which became Udaykal (Thunder of the Hills) (Kaul, 1998: 116-7).

5 Here we are not looking at the history of the concepts or normatively evaluating them by attempting a critique of the discourses in which each has gained currency.

6 The English translation of the Hindi title is given as Immortal Flame in the title card.

7 The line in the title of this essay comes from this song.

References

Arpana. “Changing role of women in Indian cinema (Column: Bollywood Country) (March 8 is International Women’s Day).” https://www.business-standard.com/article/news-ians/changing-role-of-women-in-indian-cinema-column-bollywood-country-march-8-is-international-women-day-114030500268_1.html

Arvikar, Hrishikesh. “The Cinema of Prabhat Studio. An Overview.” 25 July 2016. https://www.sahapedia.org/the-cinema-of-prabhat-studio-overview

Bordwell, David. Poetics of Cinema. UK: Routledge, 2007. https://www.davidbordwell.net/books/poetics_03narrative.pdf

Butler, Andrew M. Film Studies. UK: Pocket Essentials, 2005.

Chatterjee, Partha. “The Nationalist Resolution of the Women’s Question”. Recasting Women: Essays in Colonial History. Eds. Kumkum Sangari and Sudesh Vaid. New Delhi: Kali for Women, 1989, pp 233-253

Diwakar, Vaishali. “Maya Machhindra and Amar Jyoti: Reaffirmation of the Normative.” Economic & Political Weekly (Review of Women’s Studies) April 25, 2009, Vol xliv, No 1775. https://www.epw.in/journal/2009/17/review-womens-studies-review-issues-specials/maya-machhindra-and-amar-jyoti

Garga, B D. The Art of Cinema: An Insider’s Journey Through Fifty Years of Film History. Delhi: Penguin India, 2005.

Gopalan, Lalitha. “Avenging Women in Indian Cinema” in Ravi Vasudevan (Ed). Making Meaning in Indian Cinema. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2000, pp 215-237.

Kasbekar, Asha. “Negotiating the Myth of the Female Ideal in Popular Hindi Cinema.” In Rachel Dwyer and Christopher Pinney (Eds) Pleasure and the Nation: The History, Politics and Consumption of Public Culture in India. New Delhi: OUP, 2001, pp 286-308.

Kaul, Gautam. Cinema and the Indian Freedom Struggle. New Delhi: Sterling Publishers Pvt Ltd., 1998.

Patel, Sujata. “Construction and Reconstruction of Woman in Gandhi.” Economic and Political Weekly. Vol. 23, No. 8 (Feb. 20, 1988), pp. 377-387.

Radcliffe, Sarah and Sally Westwood. Remaking the Nation: Place, Identity and Politics in Latin America. London: Routledge, 1996.

Sarkar, Tanika and Sumit Sarkar, (Eds). Women and Social Reform in Modern India: A Reader. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2008.

Filmography

Amar Jyoti (1936), Dir: V Shantaram, Cast: Durga Khote, Shanta Apte, Narayan Kale, Chandramohan

Amrit Manthan (1932), Dir: V Shantaram, Cast: Chandra Mohan, Nalini Tarkhad, Shanta Apte, G. R. Mane, Varde and Kelkar

Kunku (1937), Dir: V Shantaram, Cast: Shanta Apte, K. Date, Raja Nene, Vimala Vasishta, Shakuntala Paranjpye and Master Chhotu

Manoos (1939) Dir: V Shantaram, Cast: Shahu Modak, Shanta Hublikar, Sundara Bai, Ram Marathe, Narmada, Ganpatrao and Raja Paranjpe.

Achhut Kanya (1936) Dir: Franz Osten, Cast: Devika Rani, Ashok Kumar, Manorama and Anwar

Jeevan Prabhat (1937) Dir: Franz Osten, Cast: Devika Rani Mumtaz Ali Kishore Sahu Renuka Devi and Chandraprabha

Alam Ara (1931) Dir: Ardeshir Irani, Cast: Master Vithal Zubeida Prithviraj Kapoor Muhammad Wazir Khan

Chitralekha (1941) Dir: Kidar Sharma, Cast: Miss Mehtab Nandrekar A.S. Gyani Monica Desai Ram Dulari Leela Mishra, Ganpatrai Premi, Bharat Bhushan

Gopalkrishna (1929) Dir: V Shantaram, Cast: Sairandhri (1933) Dir: V Shantaram, Cast: Master Vinayak, Leela, Nimbalkar, Shakuntala, Prabhavati and Kulkarni

Chandrasena (1931) Dir: V Shantaram, Cast: Nalini Tarkhud, Sureshbabu Mane, Kelkar, Rajani, Shantabai and Azurie

Un Chien Andalou (1929) Dir: Luis Buñuel; Salvador Dalí, Cast: Simone Mareuil, Pierre Batcheff, Luis Buñuel Salvador Dalí