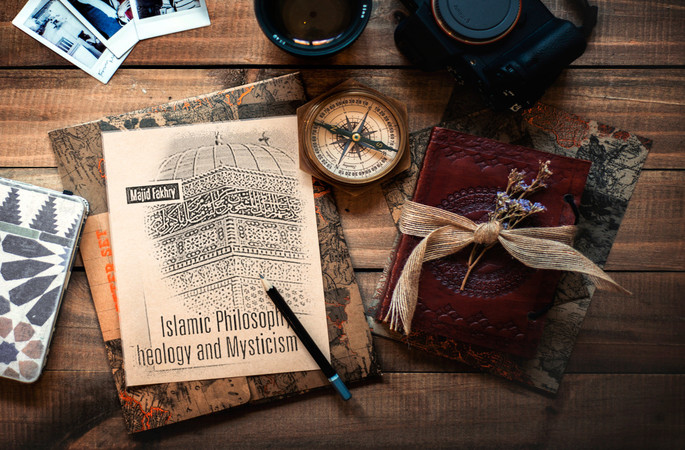

A Critical Review On Majid Fakhry’s Book

‘Islamic Philosophy, Theology and Mysticism: A Short Introduction’ is a well-written work to understand Islamic philosophy’s basic outline. It aims to introduce Islamic philosophy, its main arguments, and the historical developments for beginners. The author of the work, Majid Fakhry, needs no introduction and, he is an acclaimed professor of Islamic Philosophy at the American University of Beirut. The current Islamic scholarship considers his works on Islamic philosophy and Islamic Ethics as notable modern contributions to Islamic studies.

In this work, Fahkry prefers a different and complex methodology to introduce the subject to the general readers. Instead of just narrating the story of Islamic philosophy in historical sequence, he attempts to locate Islamic philosophy’s central ideas within the broader discursive intellectual tradition of Classical and Modern Islam. In other words, Fakhry seeks to elaborate on how Islamic philosophy shaped the discourses of Islamic Theology, Mysticism, Political Ethics, and visa versa in the cause of Islamic history.

The book contains ten chapters and a conclusion. The first three chapters bring some initial insights about the introduction of philosophical thoughts into the Islamic world. Fakhri argues that early conflicts on the question of the free will of human beings and their relationship to God’, were influenced by Greek philosophy or Christian theology’ (14). Early infiltration of philosophical ideas in the Muslim communities was a side effect of theological polemics between Muslims and Christians in regions where dominant Christian communities lived for centuries, such as Egypt, Syria, and Iraq.

They posed a substantial challenge to Islamic theology, pushing Muslims to reformulate their theology in response. Yet, these controversies had created two major theological camps within the Muslim community.

The first group argued that Islam supports the idea of human free will, and God does not have any control over his actions. The argument behind this idea is that God is just, and He cannot reward or punish human beings if He manipulates their actions.

Others supported the idea that human beings do not have the power to act freely, and God predestines their actions and intentions. He is all omnipotent, and as such, he is the owner and the mover of the cosmos.

Fakhry interestingly points out that ‘almost all subsequent theological developments would take the form of variations on, or a synthesis of, these two antithetical positions (16).

In that case, the Mu’tazila school of thought was the logical conclusion of the discourse of free will. Besides, the concept of predestination had taken its root into the theological school of Ash’arism.

In any event, initial contact of philosophical ideas with the Islamic world did not come out of systematic philosophical thinking, borrowed directly from the Greek and Hellenistic sources.

Al-Kindy was the first systematic philosopher in the Islamic history. He exposed himself directly to the sources of Greek philosophy. Yet, Fakhri notes: ‘despite his dependence on Aristotle, al-Kindi did not confine the function of philosophy to purely abstract thought; instead, he believed philosophy to be the ‘handmaid’ of religion (23). He criticised the Greek and Hellenistic ideas about the emergence of the universe. Both traditions explained the emergence of the universe in light of the emanation theory. For the Greek philosophers, God did not create the universe ex-nihilo. But it emanated into being as a natural consequence of the power of God (25). Hence, the world is eternal.

Apart from that, Al-Kindy accepted Greek ideas of tripartite classification of soul, active intellect, heavenly bodies, and the intelligible world that connects God and the world. In terms of the human soul, al-Kindi argues, it can be purified only by knowing eternal truths. In turn, the soul can attain the eternal truth by rationalist philosophical exercise. It is because the philosophical exercise empowers the rationalist part of the tripartite soul of the human being.

Interestingly, Fakhri names these philosophical ideas of purification as ‘rational mysticism’ (48).

Unlike Al-Kindy, Farabi merged himself into the Greek philosophical ideas without any indifference and supported the emanation theory as well. In the discursive tradition of Islamic philosophy, his central contribution lies in his political imagination of a virtuous city led by a philosopher.

For him, this ‘virtuous city stands out as a moral and theoretical model, in so far as its inhabitants have apprehended the truth about God’. Fakhri argues that Farabi presented the concept of a virtuous city by blending Plato’s ideas of Philosopher-King with the classical Islamic political doctrine of Caliph-Imam, who is responsible for the moral order of the community (46).

In terms of expanding Farabi’s of the political philosophy, his successor, ‘Ibn Sina does not appear to have taken any serious interest… his contribution in these two fields is comparatively trivial. However, his interest in metaphysics and logic was profound’ (48), Fakhri notes.

It was late Andalusian philosopher Ibnu Bajjah who contributed to the discourse but in a different dimension. He thought of the fate of a philosopher who could not build or live within ‘virtuous city’ led by a philosopher.

In that case, he proposed a withdrawal plane from world affairs for such philosophers. The rationale behind the withdrawal plane is that the corrupted cities, instead of virtuous cities, would affect the perfect soul of philosophers. (89)

In the following chapters, Fakhry focuses on the interplay between Islamic philosophical discourses and the mystical schools of thought. For him, the commonplace where both the philosophy and mystical discourses meet is the question of how to acquire the eternal truths.

Both the schools answered the issue in question as ‘the purification of the soul’. Yet, they differed in defining the process of the purification of the soul. The philosophers argued that it is enriching the philosophical and rational thinking of a human being.

When a soul reaches the pinnacle of rationality through the philosophical exercises, it could contact the active intellect. ‘Active intellect’ is not God, but it is a source of knowledge emanated from God’s essence and the key architect of the universe.

For mystical scholars such as al-Ghazali, rationality does not have any connection to the purification of the soul or the acquisition of eternal truths. Instead, he argued that the acquisition of eternal truths is solely a matter of spiritual experience or spiritual disclosure (Khasf), not a result of rationalist articulations. For Ibn’ Arabi, it is by recognising the unity of being or by a spiritual acknowledgement that the creator and the created are one and an integrated reality.

Concerning the emanation theory, both al-Ghazali and Ibnu Arabi used that in their cosmological arguments. Yet, the former strongly advocated the fundamentals of ‘creation theory’ as opposed to the eternality of the world.

Ibn’ Arabi interpreted it as ‘God’s love’ and rejected the philosophers’ interpretation of emanation theory as ‘natural phenomenon’. For this reason, Fahkry argues that the development of mystic tradition could be credited for the decline of philosophical rationalism in the Islamic along with the single most influential work of Ghazali, ‘Incoherence of Philosophers’.

Yet as a notable attempt to reconcile the mysticism with philosophy, Ibnu Ibn Tufayl, another Andalusian philosopher, projected that the eternal truths could be attained by both sources, either by spiritual disclosure or philosophical exercise (93).

Fakhry explores the role and place of Ibnu Rushd in the discursive tradition of Islamic philosophy in detail in chapter eight. Aptly placing him among the greats of Islamic history on religion and philosophy, the author says that ‘for al-Kindi, they were in perfect harmony, and for al-Farabi and Ibn Sina they were compatible to a limited extent. For al-Ghazali, contrariwise, the differences between religion, i.e. Islam, and philosophy were irreconcilable. Ibn Rushd, who believed both philosophical and religious, was convinced that these differences were, indeed, reconcilable’ (94).

Like the religion, Ibnu Rushd stressed, the philosophy also urges a human being to reflect on the profound truths of the reality and identify its maker.

The author then allocates a fair part of the chapter to discuss one of the great classical debates between al-Ghazali and Inbu Rush on the critical issues of philosophy. In responding to Ghazali’s key points against philosophical discourses, Ibnu Rusdh’s strategy was to broaden the interpretative mechanism of the Quran.

Thus, he argued that philosophers’ arguments concerning those controversial subjects such as God, his power, and his relationship with the universe do not go fundamentality against the basic tenets of Islamic theology. Instead, it should be considered another set of interpretation, and they cannot be labelled as ‘infidels. Because they never rejected the existence of God, his power, or the day of judgment.

They merely attempted to understand it with a philosophical lens.

In the final chapters of the book, Fahkry takes the reader through the philosophical ideas of Ibnu Taymiyyah, Fakhri Deen Razi, and Ibnu Khaldun, and Mulla Sadra of Persia. The last chapter discusses the modern trends of Islamic philosophical discourse.

Here, Fahkry identifies Ibnu Taimiyyah along with Ibnu Hazm, as anti-rationalist and the one who gave the final death blow to rationalism. It is noteworthy that contemporary Islamic scholarship did not take this argument for granted. The modern experts on the subject have already refuted these simplistic readings on the epistemological structure of Ibnu Taymiyyah.

In this regard, Jon Hoover’s work (2007) on Ibnu Taimiyya’s theodicy, Charl Sharif’s arguments (2019) on the role of reason and revelation in Ibnu Taimiyya’s intellectual framework, and Ovamir Anjum’s intervention (2012) on Ibnu Taimiyya’s political optimism are worth noting.

Finally, there is a notable feature in this work that is worth mentioning. Fakhri traces basic ideas of the Islamic philosophy by focusing on the arguments of two or three significant scholars who mainly contributed to the domain in each period of history.

Thereby, the author enabled the reader to learn the core arguments, its justifications and counterarguments, its gradual evolution on the one side, and the thought structure of Islamic scholars about the subject on the other at some time.

Yet, the author miserably fails to follow this model in discussing modern trends in Islamic philosophy. In the chapter mentioned above, I wish he could have handpicked one or two thinkers and their arguments to elaborate on the current developments in the philosophy. On the contrary, Fakhry summarises most modern Islamic thinkers’ narratives on Islamic Philosophy in the last chapter.

Concerning this approach, readers might face difficulties in understanding the shifting trends of Modern Islamic philosophy.

On the whole, ‘Islamic Philosophy, Theology and Mysticism: A Short Introduction’ is a recommended work not only for beginners but also for scholars of Islam, who are interested in exploring the interplay the Islamic disciplines in the recent times.

References

Jon Hoover. 2007. ‘Ibn Taymiyya’s Theodicy of Perpetual Optimism’. Leiden: Brill Publishers.

Carl Sharif El-Tobgui. 2019. ‘Ibn Taymiyya on Reason and Revelation’. Leiden: Brill Publishers

Ovaimir Anjum.2012. ‘Politics, Law, and Community in Islamic Thought: The Taymiyyan Moment. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)