It was a summer, Mason knew, when things were suddenly gone. In the midst of a drought, hundreds of thousands of dead fish in the Murray Basin and no one knew why. Mass fish kill, they called it. A third of Australia’s flying fox population was wiped out during the extreme heat, dropping dead from trees. People in the cities couldn’t believe their eyes. They changed channels on their televisions, escaped into Netflix or went to bed early. It was a time for letting the government know what you thought of them, for telling certain people you were sick of their inaction. It was a summer for losing precious things—a shark’s tooth necklace on plaited leather, a Valentine’s present from an unreliable girlfriend—hard to pin down, a butterfly flitting here and there. No rain in sight. I love a sunburnt country … Lake beds dry and cracked, biting insects large and thirstier than ever. Dogs, left alone in hot cars, died too. “This is what we do to man’s best friend,” said a woman on the train before turning back to her newspaper.

Mason’s golden Labrador, Pat-the-Dog, who loved him more than any woman had ever done, was suffering severely with arthritis. She only got up from her mattress to eat and drink and to go outside for a toilet break. She couldn’t jump up on the couch or climb stairs anymore. Mason was taking her to the groomer’s – LOVE DOGS LOVE LIFE – for acupuncture. The word around the dog park had been that acupuncture eased joint inflammation. You could look at your dog and think of poor tennis star Andy Murray and his hip fusion at age thirty-one. You could look at your life and wonder how long things had been like this. Ten years? Ten years stuck doing the same dead-end job—no motivation to get out and earn decent money.

The grooming salon was in the high-density eastern suburbs, on the other side of the Harbour Bridge. It was where wealthy people took their animals for acupuncture, as well as for a wash and a trim. For Pat-the-Dog, Mason sacrificed sleeping upstairs in his own room. In the middle of the night he would leave his warm bed when he’d hear his dog barking from the bottom of the stairs. He’d sleep on the couch for the rest of the night beside Pat-the-Dog who lay on the floor. “I don’t mind,” he’d say. “Who knows how many years she has left?” When he’d return home of an evening, his dog would limp towards him, wagging her tail vigorously. She would know when Mason’s car approached from a block away and hobble to the front door to greet him. The vet said the wagging tail meant she hadn’t given up on life yet, she could still find the bliss in living.

Mason had once, for a short period, lived near the harbour in the eastern suburbs but had recently returned to the north side of the Bridge when his girlfriend broke up with him. She said she couldn’t deal with “needy”. Would he ever find a woman who could love him? Confidence wasn’t one of his strengths. His shyness and unease could descend into anxiety and panic.

His ex-girlfriend was a physio at a sports and spinal clinic at Bondi and, like him, new to the area. She had made the worst meals Mason had ever tasted, salty and overcooked, but he ate them and spent long hours in her bed. However, after a while she took to working most nights. He didn’t want to ring her late in the evening, but would drive to her clinic looking for her car. It was definitely not something he’d have done in the past. He would go into the centre where she worked, quietly open the glass sliding door and look into the cubicles. He’d see the rear view of her from between the curtains massaging a back or a hairy bottom. Just where on the body exactly did tightness in the lower back end? He’d creep back to his car. What had got into him? A stalker? That’s what he’d become. A stranger to himself. A peeping Tom. Someone who walked the streets and looked through people’s windows. Soon he’d be labelled a sexual predator and his name placed on a watch list. And so, after the split-up, he left the eastern suburbs and came back alone to North Sydney. He rented a small terrace, and continued to work as a barista in an Italian café in the city. He never imagined that at forty, he’d still be making coffees.

Even now, he yearned for his girlfriend, believing their relationship had given him the security he craved. The sex had been something else, much better than her cooking. Not that he’d had much experience with women—only one other. Married. Not ideal, he’d complain to Pat-the-Dog who, as darkness fell, would tip her head back and howl at the moon. He knew there were only little moments in life—the larger ones were phases, or periods of time, that came to an end—and once you accepted that, it made life simpler and easier to bear. You learnt not to expect things to be a certain way, like a game of tennis – RAISE A HAPPY SWEAT. If you got two decent sets out of four, you were lucky. No-one scored four out of four.

After leaving his dog at the groomer’s on this particular day, Mason hurried in to the city. He worked at Munch More Italia, a heritage listed Italian café and gelato bar on the corner of an arcade. He minded the register and made the coffees. His co-workers were two newly-employed twenty-something women. Gizelle did the cooking and Claudine brought out the orders. Mason enjoyed the interaction with customers. ‘Small, medium or large?’ he would ask enthusiastically.

‘Do you want sugar?’ he’d enquire, watching as they’d pay with a tap of their cards. If it was a woman he thought pretty, he’d say, ‘You’re sweet enough already,’ and give a smile, even though they rarely smiled back. Sometimes a homeless person, one of his regulars, sleeping rough in the park or under a bridge or on a train, would come in and join the queue, and he’d give them a coffee or a can of coke, like a caring chaplain. Not that he believed in religion: all religion is a construct.

‘A bit on the late side, aren’t you?’ said Claudine today. She was pulling at the cropped black netting top that covered her sports bra, and seemed upset. Her hair looked unwashed and was tied in a small bun at the nape of her neck. She wore cotton figure-hugging leggings that looked like she’d forgotten to put on her skirt. All the same, he thought she was very cute.

‘I had to make the coffees as well as serve the customers,’ she said. ‘Lucky I know how to do everything.’

‘Thanks for covering for me. I took my dog for acupuncture this morning, all the way to the eastern suburbs. Many customers?’ Mason gave Claudine a worried glance. It said, ‘This is a oncer.’ It also said ‘We help each other out, don’t we?’ and ‘This humidity is a killer.’ The summer heat and humidity bonded Sydneysiders in solidarity. It was like going to the same church on a Sunday. You were all in a crazy world together.

‘No. Not many customers, just a couple of takeaways.’

‘Well, thanks heaps.’

Claudine scowled. ‘No worries,’ she said with a touch of sarcasm in her tone. Claudine didn’t like to have to deal with the coffee machine. Learning something new made her nervous. No matter how many times Mason patiently showed her how things worked, she objected sighing deeply and rolling her eyes. But he was always happy when he could find a way to help her.

Claudine lifted the glass lid covering the freshly baked scones. She grabbed the lone date scone in her fingers. Loose flour spread across the counter. She took a bite. ‘Have you ever been mountain biking?’ she asked Mason.

‘Mountain biking?’ Mason said, surprised. As far as he knew Claudine was fiercely opposed to all forms of physical exercise.

‘Yep. Mountain biking. You know—with the extra thick all-terrain tyres,’ she said wistfully.

‘Once a couple of autumns ago I went mountain biking in the Snowy Mountains. These days I use a stationary bike in the gym.’ His girlfriend, the fit and muscly physio, had loved outdoor adventures. ‘Extend yourself, Mason,’ she had said to him. ‘Get a life apart from your job and looking after your dog.’

‘Stationary bike, forget it,’ said Claudine. ‘There’s no adrenaline hit, no danger. It’s nothing like cross-country cycling.’

Mason looked up from the espresso machine. So … Claudine has an adventurous spirit. Interesting.

Claudine sauntered away, every muscle in the cheeks of her butt rippling like a race horse’s rump.

‘What will it be today?’ Mason smiled and held out the menu. ‘Are you eating – or is it just a coffee?’ Beside him on the counter was a bowl of tiny shortbread cookies. He would put one on the saucer of each coffee. The sign on the wall behind him read: LIFE IS SHORT, EAT THE COOKIE.

A woman with a necklace of colourful glass beads like his mother used to wear reached across the counter and helped herself to a cookie from the bowl. ‘A small flat white thanks,’ she said. He was about to take her money when he heard someone out in the arcade call his name.

‘Mason! Mason! How are you mate?’ Mason looked at the man and for a moment couldn’t think who he was. But his smiling face gradually slotted into place. It was Bradley, a friend from decades ago. It was strange how someone, when they stood still and you had a really good look at them, hadn’t changed at all. No matter how much a person’s hair might thin and recede, the man with a denuded forehead still included the boy.

‘Bradley, you look terrific. So, what’s been happening?’ It seemed a crazy question to ask a person who you hadn’t seen since high school days.

‘Well, two years ago I fell in love with the woman of my dreams.’ Bradley’s voice intimated there was much to tell. ‘We got married and moved back to the city after living on the south coast for yonks. I’m still teaching.’ Bradley reached over and helped himself to a shortbread cookie and then one more. Crumbs cascaded down his T-shirt.

‘You look so happy,’ said Mason.

‘That’s it exactly. Happy. I keep bumping into guys from the old rugby days, we’ve been getting together for a game and a drink. Mason, you should come with me tonight to the try-out.’

‘I’ll think about it,’ said Mason. But what if he pulled a muscle, couldn’t walk, was unable to work, had to take time off? His life would be ruined. He would be isolated from the world and probably lose his job, and wouldn’t be able to take care of his dog.

‘Give it some thought,’ said Bradley and took another cookie from the bowl. ‘These are great. Melt in the mouth. Where do you live now?’ Bradley brushed the crumbs off his T-shirt.

Mason picked up the bowl of cookies and placed it behind the counter. ‘North Sydney. What about you?’

‘We’re renting a unit at Kings Cross. There’s a gym and pool and you can walk to the train station, which is what attracted us. You know what Sydney traffic is like.’

After work Mason drove back to the east to pick up Pat-the-Dog from the acupuncturist. Mason had promised Bradley that he would meet him at six-thirty for the try-out, at their old sports ground, but his hands went cold and clammy at the thought. He tried jogging on the way to his car, to check how fast he could run. His knees weren’t crazy about the hard landings on the concrete surface although Pat-the-Dog was able to trot briskly back beside him.

It was just something small, a small change—NOTHING CHANGES IF NOTHING CHANGES—but Mason decided not to subject himself to the risk of the try-out. He rang Bradley and gave his apologies, said his asthma was playing up again, and Bradley said, ‘The centre of the city is full of dust with all the upheaval for the new light rail. Rats too. Come over for a meal one night this week, if you’re free,’ and Mason said that yes, he would.

And he did. He caught the train from the city to Kings Cross the following Friday and had dinner with Bradley and Bradley’s wife, a gorgeous big-hearted woman who worked as a publicist for a marketing company.

He could see why Bradley had described his wife as “the woman of his dreams”. She was wearing a beautiful white floaty calf-length dress, like the delicate white linen blouse and skirt his ex-girlfriend the physio had worn when she came to visit for a final goodbye. It had been a magnificent outfit, falling in seductive folds, and she had worn it when they had walked that Sunday around Balls Head Reserve with its views of the city skyline and harbour and the arch of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. The harbour had spread before them, a rich deep blue, an intense ultramarine. He had touched the white linen, put his arm around it, in the forested headland of red gums, cypresses, blueberry ash and figs—a moment that would be etched forever on his brain.

After dinner Bradley walked him to the bus stop and said he’d give him a call.

But it was nearly Easter by the time Bradley rang, and Mason was too busy preparing Easter gift packs for the café. There were chocolate bunnies and hot cross buns and he was trying to blow up a plastic Easter rabbit in a bow tie to welcome people at the entrance to the store. In the middle of it all Claudine announced, ‘I have to resign.’ She needed to fly back home to visit her sick parents.

‘I’ll miss you,’ said Mason.

‘Well, make sure you stay in touch. You know … we could always meet in the park with our fur babies.’

So … she’s a dog lover. Another surprise.

The day she left, Claudine brought in a box of special salted-caramel chocolates, and she and Mason ate them right there. They tipped them out on to a paper serviette and nibbled, cross-legged on the floor behind the gelato cabinet, bobbing up from time to time to make sure no-one was waiting to be served.

‘To the bliss of pigging out,’ toasted Claudine. A small blob of chocolate escaped from her mouth and landed on her perfect delicate white linen blouse. Claudine flicked the chocolate off, but it left an incriminating stain.

‘To finding the bliss,’ said Mason. Chocolate coated the front of his teeth. He savoured it, his tongue sweeping back and forth around his mouth, like a windscreen wiper before he swallowed the last serotonin-producing morsel.

After closing up early they opened a packet of Easter buns, which was slightly torn at the corner. Mason ripped open the packet with his teeth, imitating a prehistoric caveman. He put on some disco music and they mouthed the words while dancing to Sweet Lovin’. He pretended to play a guitar, he shimmied, and struck a pose. Why not? Life could be fun, but you needed to open the door wide, rather than peeping out. You could still find bliss out there.

‘Salsa dancing,’ laughed Claudine, throaty and soft. ‘That’s what we could do.’

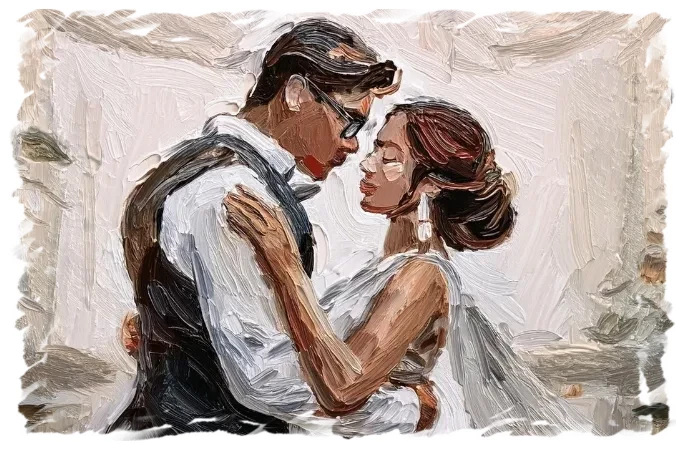

He took her hand, spun her around under his arm, reeled her in, drew her close, and with a sigh she let herself fall into his body.

‘You’re a lovely girl, you know.’

On tiptoes, she hugged him. ‘I’ve always had a soft spot for men with thick hair like a lion’s mane.’

Inside the gelato cabinet, the peaks of the sorbets, yoghurts and ice creams were labelled with hand-written tags, like place settings around a table at a dinner party. Mason leant in and selected the tag that said, SALTED COCONUT AND MANGO SALSA.

‘Here,’ he said to Claudine. ‘Take this.’ He handed the tag to her and said, ‘To salsa dancing. You and me.’

Claudine attached the label to the breast pocket of her blouse so the chocolate stain was hidden, and the pristine white blouse glowed, imperfect, but blissful.