I was educated with words.

What I discovered about painting through painting

is that it is a language that can go as far as any other language.

It is not a surface thing. We are used to communicating with words.

Painting always seemed like something exotic.

So I discovered that it’s a language that’s not meant to be translated into words.

Etel Adnan

When I first got familiar with the work of Etel Adnan and read about her life, I felt as if I had met a close and familiar old friend. A true hybrid who lives her life in the intersection of different linguistic and cultural experiences, Etel immediately became a great inspiration for me.

Etel was born to a Turkish-Greek family in Lebanon and acquired French as her primary language of communication and expression. However, she soon realized that French in Lebanon was the language of the oppressor, and she sought the opportunity to free herself from it. Therefore she developed a relationship with English, which, as she writes (Adnan, 2016:32) freed her from “the ghosts of the past and made her feel like an explorer, as if every word was just being born, the expressions were creations, the adverbs endlessly endless, the verbs were shooting arrows, one simple pr0position like ‘in’ or ‘out’ was a whole new adventure! The writing seemed like a sport, the sentences like horses, opened up roads ahead of them with their power and it was so good to ride!” (Adnan, 2016: 32, my translation).

However, her relationship with her language of origin, Arabic, never ceased to concern her. For a long time, she found escape in painting, a new language with no need for words, but with colours and lines instead.

She writes: ‘It was not necessary to belong to one culture, marked by its language, but I could dedicate myself to a new form of expression. I learnt that there were many painters who had solved the language issue, mainly painters who had grown under the French culture. My spirit grew. I realized that it is possible for someone to proceed towards many directions: that the spirit, in contrast to the body, can move towards many dimensions simultaneously, that I could move not only on certain levels, but inside a spiritual world, and that what we consider a problem is possibly a bundle of tensions that functions mysteriously and surpasses our understanding. In time, as I taught in English, I felt all the more comfortable in this language. This particular language I did not use anymore, but I lived it.” (Adnan, 2016: 28-29, my translation).

Adnan’s search for creative expression seems to be very closely related to her life’s search for personal freedom. This becomes evident in the way she has described her experience with the English language above, in terms of riding a horse that takes her to various directions ahead. Likewise, her relation with painting, colours and lines, gave her the freedom to move towards various dimensions, without language restrictions, and with the opportunity to overcome the dominance of the French language.

In relation to Arabic, Adnan writes: ‘I grabbed the poetry written by important contemporary Arab poets and worked with it. I did not try to ask them to translate it for me, the paradox of what I could understand, extracts of sentences here and there, phrases from which I could only understand one keyword. It was like looking through a veil, like gazing at a grand landscape through a screen, as if the screen did not delete the pictures, rendering them even more mysterious than they actually were.’ (Adnan, 2016: 33, my translation). The limited understanding of her ‘native’ language, Arabic, seems to give her the freedom and expand her creativity. ‘Seeing through a veil’, as she describes her own understanding of Arabic, makes the pictures and the landscapes all the more magical, mysterious and simultaneously attractive.

Although she states that she feels herself to be in exile, she experiences the exile as her second nature, and ‘there are moments when I am actually happy’ (p. 38, my translation). Although she lacks the feeling of the direct communication with her audience, she belongs to the continuously increasing group of writers who ‘use a language other than their own due to history or exile or pure personal choice’ (p. 37, my translation). In any case, as she puts it, ‘poets are deeply rooted in language and surpass language’ (p. 38, my translation). Finally, she sets herself free from feeling guilty about her inadequate knowledge of her own language, Arabic, describing her deeper self, her weaknesses which are paradoxically also her strengths, as follows:

‘When the sun is strong and the sea is blue, I cannot close my windows and stay inside to ‘study’ anything. I am a person of the eternal present moment. Arabic remained a forbidden paradise to me. I am simultaneously foreign and native to the same land, the same language that ‘should’ be my mother tongue. This century has often told us to stay alone, to cut off all the bonds, never to look back, to go and conquer the moon. This is what I did. This is what I do.’- (p.39, my translation)

For Adnan, language is an issue of origin, migration, identity, colour, space, oppression, freedom, exile, home, art, spirit and an art form itself.

Reference

Adnan, E. (2016). Γράφοντας σε μια ξένη γλώσσα (Grafontas se xeni glosa). (Μτφ Βασιλική Γκέτσιου/Trans Vasiliki Getsiou). Αθήνα/Athens: Εκδόσεις Άγρα/Agra.

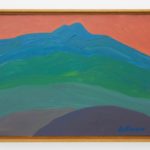

To see some of Atel Adnan’s works see below

Images Courtesy of Callicoon Fine Arts, New York

Click on the photos to enlarge