Worked on in upcycled denim, this Quilt was a collaboration between a daughter and mother. It could have been just an ordinary family heirloom. However, it foregrounded several facets of family, community and village life in the way it unfolded.

The denim fabric, though chosen by default, is imbued with symbolic power. Indians craved for a ‘jean pant’ from the 1950s. It was the gift you requested as a youngster when a father or an uncle was posted abroad. When acquired, you wore the fabric with a panache. You had your coming of age party, your first success or failure, your first wet dream, first smoke, first date and first kiss in this ‘fabric of Nimes’. If you did not own one you could get away with stealing and borrowing it. Globally there were enough influences to enslave the Indian mind to jeans. The hippies wore them, and so did the rich, the grunges and the hip-hoppers.

Hence, using old denim was not only ecologically appropriate but proved a surface that came with a life of its own. One pair of jeans had been worn when the wearer witnessed the breaking of the Berlin Wall. Another had been worn on a 24-hour escapade by a teenager on a bike escaping the wrath of his girlfriend’s father. Yet another was worn when he proposed…The stories were diverse and powerful.

I had brought a pile of my boys’ outgrown jeans when relocating to Goa in 2004. My mother saw the pile and remarked: ‘You are not throwing those away are you?’ ‘No ,’ I replied unwittingly. But the embryo of the quilt idea had already begun to swim in the umbilical waters of my mother’s mind. We added to the pile some outgrown donations from nieces and nephews in the same age group as my adolescent boys. I began a new life in the state and got busy with founding a pre-primary school, writing and painting. Protests against a new megaproject that was being planned in the village took up a major part of my time. I forgot about the quilt and our destined collaboration.

My mother passed away in 2015. When sorting her cupboards, I found this huge tarpaulin-like object. Heavy and mouldy, it was a quilt my mother had embroidered and stitched. ‘I can make a tent of it for my daughters,’ said my son, who was helping me sort her belongings. There was no way I was going to waste all that embroidery.

During COVID-19 time, I resised the embroidered pieces into quadrangles and joined them together using a crochet border. It took me a good three months to do so. It was then that the embroidered pieces in the quilt began to speak to me! There were flowers, domestic animals, birds and pets depicted in the embroidery. My mother had been a well-known embroideress in her time and had embroidered vestments for the church, trousseaus for brides and other wedding finery. Beautiful as well as some strange-looking specimens peopled her quilt. Many of the orally passed down stories of my childhood seemed represented through symbols. Using symbols in embroidery was a method employed by the church. Christ was represented by a lamb, a bunch of grapes symbolised wine which stood for the blood of Christ, and a sheaf of wheat represented the host, which stood for the body of Christ.

Many women of her generation used the domestic sewing machine to leverage their lives and become economically independent. My mother had set up a sewing and embroidery school before I was born. It was a fun school as far as I could remember, the girls sewed, laughed shared food and anecdotes. It certainly was a better place to be than my school, which had rules and punishments.

When I grew up, I wanted to be an embroideress like my mother! But that was not to be. She taught the trousseau-making girls, the marriage-proposal awaiting ones as well as my cousins but not me! But not me! This created a major rift between us when I was growing up. My paternal grandmother somehow understood this with her wisdom and taught me crochet. Seated on a caderinha (small chair) by my Avo’s side, I struggled with a steel hook over looping singles and double trebles, as she instructed as well as narrated intimate episodes from the liberation of Goa. My uncle Antonio Viegas was imprisoned at Aguada for over five years. Another uncle Nuno had escaped to Bombay disguised as a beedi-seller. She unfurled the planning scenario as well as mapped these journeys. Her voice and her stories probably made me the rural flaneur I am today. It is strange, is it not that you sow in one generation and reap in another!

Many of the symbols in the quilt and the oral stories are stories of good counsel and cautionary tales once in oral circulation from a quintessential Goan village, now fast disappearing under the bane of modernity. But the core of these stories had happened in real time and may have been embellished by the teller to increase their appeal and retention. So what I have done is merely unravel these stories from the motifs and symbols on my mother’s quilt and hand embroider them on spill-over pieces from the original quilt.

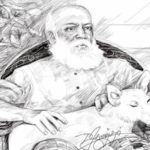

Machine and hand embroidery was always perceived as women’s work and reified in artistic hierarchies. Hence rather than paint the stories, I chose to embroider them as a tribute to my mother. In 2014 when I had my second solo exhibition, I remember 82-year-old Mae going around the exhibits and reading minutely. When I was within earshot, she asked me: ‘ What is the price for this one?” When I told her, she kept a hand on her heart, exclaiming,’ Meu Deus, I don’t even make that much profit in a year as an embroidery artist!”

Needlework has a relationship with politics, power and resistance. Craft techniques have been used to explore the construction of gender roles and challenge hierarchy that valued painting and sculpture over women’s work. Women created arpilleras in South America in the time of Augusto Pinochet, the Chilean dictator. In them they memorialised family members disappeared by the regime. It was a crime to own an arpillera during the Pinochet regime in the 1970s and 80s!

I used the feminine aspects of the medium but was not restricted by them. The work had a lot of intertextuality, as on the already used denim, a secondary layer constructed a new narrative that was older than the jeans. The result was a palimpsest in which the struggles and anxieties of another generation are superimposed for the consumption of a new generation.

In embroidering the panels, techniques employed by the carvers of the Sanchi stupa medallions and torannas were used. The carvers depicted Buddhist lore in ingenuous ways, collapsing linear narration. Oral stories were embedded on cloth and had to be decoded by reading textual stories as much as knowledge of the jatakas was vital to decoding the representations on the torannas and medallions. Story narratives are encoded in the design itself. Embroidery has it all. Social cues, family, community and village associations.

I am a figurative painter and embroiderer. Each piece evolves by itself to unfurl its narrative. A journalist friend visiting the exhibition remarked, ‘ Your embroideries are so colourful and appealing, but the stories have violence and are something else.’ Yes, one can use embroidery to tell powerful and disruptive stories!

There were ten discernible stories I could pinpoint to my childhood and find a link. A proud artist like my mother would never depict ugly motifs in embroidery for her, it was an art through which beauty had to be revealed. There were beautifully created flowers and roses but a whole genre of the same had been created in green applique and were diametrically opposed in comparison. This made me track back these stories and locate their meanings. The oldest of these stories is Tiger, Tiger! dating back to the 1890s and now is known to my grandchildren. Human/animal conflicts due to the dislocation of habitat have been highlighted in The Hungry Tide by Amitav Ghosh. But such altercations occurred in our village a hundred years ago. Should we not tell our own stories to the world? The story of Gabby you be Beleza is a piquant 1960s narrative about two transgenders who meet and find love. This story was an important tale about how two people, who figured outside of the heterosexual village community, came together as outliers, no doubt, but villagers nonetheless. Flower power! narrates how abused children take agency to destroy their abuser. The stories were complex at times confronting traditional wisdom, but had at the core of their telling a brief to protect, uphold and engender family village and community.

Tiger, Tiger

It is May. Argentina is husking the rice, the toddler Natividade, her first child, is playing a little way from the pounding section.

“Ah, ah, ah.” She grunts ceaselessly, lifting the milling shaft and crashing it into the urn filled with paddy.. Her feet are set wide apart as the ripped grains and husk fly.

‘Suddenly…’

Heeh Heeh. Heeh

Argentina turns around and what does she see?

A huge tiger with soot and ash on his face panting at the open door.

He is more panic-stricken than hungry and she backs toward her child.

She trails him now with the child on her hip and her sweat flowing in gushes.

She closes the door after he enters a room and goes to alert the neighbours.

But she has lost her tongue and can only pantomime a tiger.

Flower Power!

When the lamps had been put out and my grandmother was fast asleep my sister and I dreaded the creak of the door!

We never spoke about it. But I could hear her crying long after the door creaked again after him. On other nights it would be my turn and I would be helpless and angry.

Our parents had died young and we lived with our grandmother and uncle. It was not a happy family. Relations had become strained when my father married. The house had been partitioned to accommodate the two nuclear families. The vicar intervened when our parents died, for I was twelve and my sister nine.

It was then that my grandmother combined the households and took charge. My sister continued to go to parochial school but I was withdrawn from school and made to keep house.

That Sunday night, when he left our room, he said,

‘Make rabbit stew tomorrow.’

I ground the seeds and mixed the sap. The tangy taste in the rabbit stew came from a dash of tamarind.

The uncle turned blue an hour after he finished his lunch. The remains of the stew were fed to the pigs who died mysteriously.

The door to our bedroom across the corridor never creaked again after the lamps were put out.

Artist, writer, and historian Savia Viegas reflects on her latest exhibition, Quilting Stories, which was on display at the Museum of Goa until May 15, 2024.