Several years ago, a young English couple came to honeymoon in the hill country of Sri Lanka. Part of their stay was in a wonderful hotel which was built in a former tea factory.

Some of the pieces of equipment used to process the tea plants were on display as objects of interest, throughout the hotel’s spacious lobby and landing.

The young man said that the view from their room was beautiful. Jewelled tea plantations, laid out like velvet green carpets as far as the eye could see. But there was a section of the view which contrasted starkly to the perfect landscape. When he asked the management what that was, he was told that was where the tea plantation workers lived – in what were called ‘line rooms’. Here they were housed in crowded conditions and often unsanitary quarters, and from here they came each day to pluck tea and make the factory and tea plantation owners prosperous.

The management of the hotel offered to have the roofs of these line rooms painted green so that, when viewed from the upper floors of the hotel, they would not be so unsightly. The young man and his wife decided to establish a school, and offer an educational /vocational programme for the children of the estate workers, so they could improve their lives and the standard of living of their communities. Their project, The Tea Leaf Vision Trust, now runs several schools in the upcountry area, and hundreds of students have graduated with certificates in English and vocational skills which make them employable.

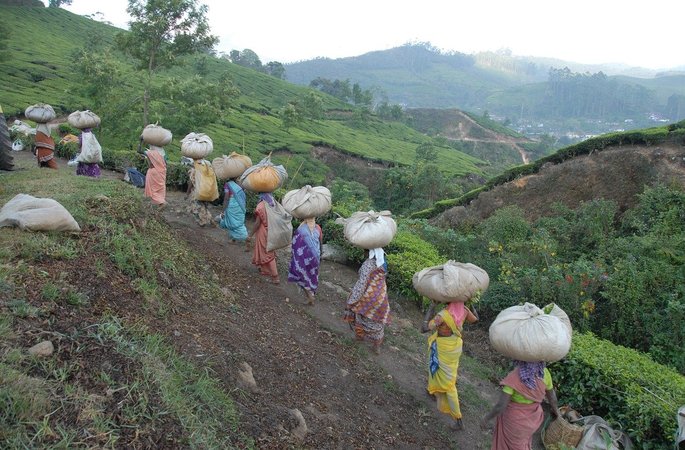

Recently on Twitter, a photograph was shared which showed a row of estate workers, many wearing masks, standing at an approved distance from each other in a curving line on an estate road, framed by the tea bushes they plucked.

These ladies are often portrayed as smiling in colourful attire in advertisements and tourism promotions for Sri Lanka. In this picture, they are not smiling – perhaps their smiles cannot be seen because of the masks they have been told to wear. The caption to the picture, adorned by hashtags like ‘StayAwareStaySafe’, praises the ladies for their model behaviour: ‘We have a lot to learn from the discipline shown by our beloved estate workers’.

The photographer and the writer of the caption failed to note that this admirable social distancing at work is not – and cannot – be practised at home, in the crowded living conditions of these, the poorest citizens of the Sri Lankan community.

The ‘discipline’ that they are praised for comes from the economic reality which forcefully operates on them: if they do not work, they do not get paid.

They are day labourers, and if they want food on the table they have no choice but to go to work, no matter the weather, and despite the curfew restrictions people complain about in the urban centres.

The urban elite in Sri Lanka is often ignorant of the situations of the estate plantation workers. With white-collar jobs and university or college qualifications, and educated in the country’s most well-funded schools, their lifestyles and those of their own children encompass access to restaurants, cafes and hotels, and holidays at overseas resorts. The tea plantation workers are seen as part of the setting of an upcountry holiday, adding ‘authenticity’ to the local atmosphere. To think of them that way, as props in a landscape, is to diminish their humanity and their life experience: a perpetuation of the legacy of social injustice conceived and created by colonialism.

The legislation is still, in 2020, to be affirmed which guarantees these ‘disciplined’ workers 1000 rupees a day for their back-breaking work. We feel sure that they would prefer to be properly protected and paid, rather than called ‘beloved’ – and finding their lived realities painted over, to make them acceptable to the eyes of those who profit from their labour.