In between work and raising the kids, I tried to be a loving wife. My husband didn’t want me anymore. Late at night, I escaped into writing. At bedtime, I’d read to my children, as they were the stars of all the adventures.

When my husband left, I lost the will to live. I always believe that I got cancer then. It was over my heart.

It stood out like an egg on my breast.

My breasts weren’t youthful anymore. They showed the stretching of pregnancy and feeding of my two babies. Nowadays, they drooped a little, and when I lay on my back, they’d veer to the side. I was lying on my back when I felt the lump, pressing into me like a gluey ball. I tried to force it away. I pressed and pressed the lump until it was sore and red. But no. It was stuck inside my body. Panic shivered through me.

……………………….

I’d married at university to my first love. I was 19. He was 21 and an engineering student. We’d been together for twenty years and promised that we would love each other forever. But he left for another woman anyway. It was like he’d gutted me, and I lay bleeding in our double bed. I couldn’t get up. I wanted to stay in that bed until I didn’t breathe anymore. My children lay next to me, but I could hardly feel their warmth. “Can we have dinner Ma?”

Their voices were distant. But they kept asking, pulling at my clothes, until I answered. No. I can’t move. I can’t make dinner. I’m dying, my darlings. “Yes, of course,” and I made dinner and struggled through the days.

………………………….

The lump was attached to my heart. My stomach heaved. I’d given myself cancer. I believed that. I felt like a coward. I held my stomach gripping pain as if it was tangible. I stroked my little daughter’s soft brown hair. My son said to me. “It will be all right, Ma.” He was always brave. I had to be here for them, listen to their stories, tell them stories, hold them when they were frightened of shadows.

I battled out of my bed and got my children ready for the day. I pretended to smile, but my daughter knew there was something wrong and held my hand. “You will never die, will you Ma? You’ll never leave us, will you?”

How did she know? “No, I won’t leave you,” and I pretended that there was nothing wrong.

Monday afternoon. The Breast Clinic. I hoped the receptionist would say there were no appointments available. I hoped that I couldn’t get a referral. I hoped.

The waiting room was basic. I was ashamed of my breasts as I exposed them to a young male registrar. Or maybe he was an intern. There was prodding and poking and talking behind curtains. My mind was blank. It was as though the hands prodded someone else’s breasts and I was an observer. A specialist arrived and asked when I had my first periods. That was so long ago. So silly, embarrassing and I didn’t want to answer. I was thirty-nine years old.

The mammograms squished my breasts and I waited. More squishing and I waited. More … The ultrasound was a relief with the wet jelly smoothed over my breasts and the cold hands of the radiologist. Everyone spoke to me too kindly. There were uncomfortable looks among the nurses. A doctor walked with me to another surgery. She said that the mammograms and ultra-sounds were suspicious. Breast cancer. Suddenly I thought of my children and I cried, right there in those hospital corridors. The doctor put her arm around me.

The biopsy needle pierced into my breast and I didn’t care. Then the other breast. I didn’t care. It was my fault. The surgeon had a worried look and I wanted to laugh. He didn’t realize that I knew. It was my fault. I let my husband break my heart. Cancer.

I hid the cancer from my children. They couldn’t know because they’d be afraid. My husband couldn’t know because he’d fight for custody. My work couldn’t know because I needed employment. I waited for the Easter holidays. The doctor was worried as I delayed surgery. But I had to. For the children. So, they wouldn’t know.

Easter was always the time my husband took the children for two weeks. I hugged them tightly. Gave her favourite teddy to my little girl and made promises I would be here for them. Would I? Then I drove into the hospital. I admitted myself, answered the same questions again and again, walked through the wards following a nurse. I stripped, put on a white hospital gown.

“I don’t want my breast cut off,” I begged the surgeon.

“We’ll see.”

I woke up to drips and blood draining into plastic bags. And I vomited all night and the next day and the pain from the removal of my lymph glands was terrible. They didn’t take all my breast. Just a part and even though my breast was stretched and droopy, there was a piece torn out of it. They didn’t know if it had metastasized yet. It hadn’t.

The radiotherapy, chemotherapy, the drugs, the healing. It was long and I was tired. The days driving to the hospital; the procedures – stripping naked and metal plates and machines squashing and burning my breast; my kids in the waiting room drawing pictures, not knowing. At night I crawled under my doona. My children slept next to my bed on mattresses.

The weeks passed as I struggled through work, stressed over custody and settlements, cried over betrayals and infidelities. And I loved my children who felt the world was unsafe.

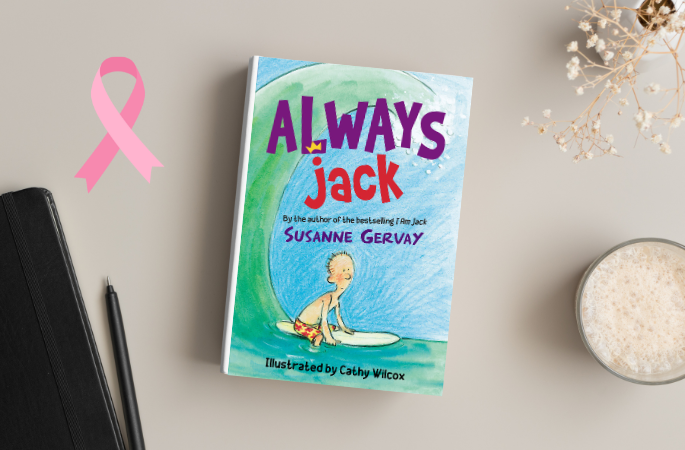

The Cancer Council told me that their books did not reach young people. Their instructive non-fiction books did the unravel the mystery of cancer. It became my mission to write a book filled with the joy and heartbreak and the hopes of young people.

I was deeply touched when Cancer Australia’s Dr V Milch critiqued Always Jack, gaining approval from the medical researchers and teams working with cancer. She wrote:-

“Susanne Gervay’s Always Jack makes it safe for children, parents and the wider community to talk about cancer. Written from the perspective of a boy, Always Jack is engaging and enjoyable to read. It weaves accurate detailed clinical information into a children’s style, in an easy to read, educational, empathic and understandable manner. Impressively, it covers many aspects of a woman’s experience with breast cancer, including:

Screening mammograms

The triple test: Diagnostic mammogram and ultrasound, biopsy

Surgery

Lymphoedema

Hormonal treatment

Men and breast cancer

Psychosocial implications for the child – fear of losing his mother , of things not being “normal”

The message of the novel is hopeful and encouraging whilst not shying away from the child’s pain and fears, using humour to sensitively appeal to a child about a difficult subject.” Dr Vivienne Milch validated my journey.

Always Jack carries the Cancer Council’s yellow daffodil on its cover. Published by HarperCollins, it puts my arms around our children to keep them safe.

Ten Years Later.

I had breast cancer at forty-eight. I looked up at the beautiful blue sky and thought I would never see it again. They cut off my left breast. I had massive lymphoedema and my heart was naked. I did not die.

Another Ten Years Later

I had breast cancer again at fifty-eight. But I had changed. I knew that I couldn’t die yet because my children and grand-children needed me. Because I had a mission that all young people need to feel safe and embrace hope.

My ex-husband went on to have another family. The decade of court cases ended. My children have grown up into amazing people. There are three beautiful grand children. My passion as a children’s and young adult author continues to grow. I continue to have cancer check-ups. Although, I still believe I gave myself cancer, there is a commitment to live.