I conduct a continuous dialogue in my mind with myself, in the form of a conversation with a psychotherapist in a clinic on the tenth floor of a building that feels like a skyscraper. The other self in front of me is sometimes a white female doctor, whom I constantly and deliberately hurt, unloading on her my psychological burden and the traumas of our generation in this accursed place. Not for any particular reason, other than the fact that she is white. Let her carry the burden of her forefathers.

I don’t know when or how I enter this clinic, but I always find myself returning.

Sometimes the dialogue is simply with myself. My memory begins with the Second Intifada, when I was in the fourth grade. A Druze soldier (one of “my people”) threw a stun grenade at my younger sister and me while laughing. Our neighbour rushed to rescue us after hearing our screams. Yesterday, I saw a photo of the Merkava tank in Jenin Camp. A numbness spread through my limbs. During the Second Intifada, things grew harder for people. Schools and universities shut down, as did the little stores (which were at best called mini markets, not malls or supermarkets). A curfew was imposed once, and I went to the store when it was briefly lifted, but the soldiers decided to make things even worse by redeploying before the lift ended. I darted through the red shop door, only to find the Merkava passing right before me. I turned back, my throat hoarse from screaming.

During the large-scale invasion, our home was split in two, half for us, and the other for my cousin and his friends who couldn’t reach their cities due to the invasion and checkpoint closures. Away from the Merkava, the soldiers, and the settlers near Joseph’s Tomb, neighbours helped each other as best they could with eggs, flour, and water that aunt Um Bulbul would pull from the well. After the curfew was briefly lifted and the young men had left, I found a deck of playing cards made from notebook paper in our room. Our guests had fought off boredom and anxiety about the tank and the soldiers with cards cut by a ruler and inked in blue.

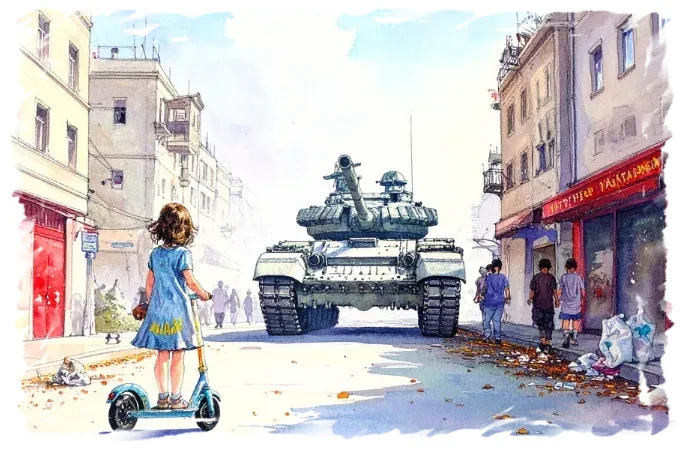

At that time, before shopping centres (whose names I don’t even know) invaded the square area of Nablus, there was a gift and cassette shop called art (a.r.t.). Entering it during Valentine’s season was practically a crime. We used to buy music tapes from there, before CDs took over. That’s where my mother bought my sister her Walkman, gold and black, with tiny, fragile headphones. I don’t know exactly what the shop has to do with any of this, but after endless nagging, my mother also bought me a scooter, a blue scooter with yellow writing on it. One day during the long invasion, I took the scooter and headed up a side street near our neighbours’ house, since the Merkava didn’t usually pass that way. Suddenly, I found myself face-to-face with it, just me, my scooter, and the neighbourhood kids.

Where did I get that courage? I was a bold child who faced the boredom of the Intifada with a scooter and a bag of chips from the corner shop. Today, I am a very cowardly woman who runs from a raid taking place dozens of kilometers away. When did fear start beating me to the scene? I’m a coward, and my stances are firm, but they are also unstable and emotional. Today, a poet from Gaza, someone I don’t know, and who doesn’t know me, visited me in a dream. She sent me messages asking if I was happy to have a Merkava among my children, like she does in Gaza.

I will go to the white therapist. I will place my memory in her hands and watch her crumble. I’ll tell her about the dream, and I’ll embellish it with harsher scenes. I’ll tell her about the nightmares of dying under rubble that haunted me throughout the genocide, and the time I woke up next to my husband, calling out for my sisters, as if I were back in our room during the invasion twenty years ago. I will conduct deep research and memorise people’s stories and tragedies. Even the photos of the young men in Jenin posing with the tank, I’ll tell her they’re drowning in denial and can’t sense what’s coming. I’ll tell her how we try to turn the hardest and most painful moments into jokes we chew like gum. I will make sure she is infected with our curse, our illness, or our torment, whichever it may be.

Yesterday, I saw the Merkava on Telegram, and I heard the sound of its treads in my ears. I remembered my scooter and a time that was more blessed, when a bag of chips cost three agorot, and when we only knew a raid was happening because we saw it. When a raid was really a raid or an invasion, not a “sabotage operation” or “activity.” I saw what I saw, and remembered the war that never stops, in our minds, on our streets, and the roads between cities. I looked at my two daughters and said ‘This summer, I will buy both of you a scooter.’

Our memories are our children’s memories. Our memories are also the memories of the generation to come.