Draksha-cha Sharbath. Sherbet of raisins. Our cups overflow with this special drink for Shabbath, or to break the fast at Yom Kippur. Fresh wine made from long, black raisins we bought from New Market in Kolkata for these occasions. Instant sugar high for a kid like me, or for adults who had fasted all day. Such sweetness, such satisfaction. And we believed, just like in Keats’ “Ode to Autumn,” that everything was “conspiring with the sun…to load and bless” us with abundance, and like the wasps, we thought “warm days would never cease.”

In Keats’ poem, the figure of Autumn watches the winnowing of grain and the pressing of apples as she sits in a field or shed. I, too, was a witness—to the making of our simple sharbath. Hannah, my grandmother, was the real head of the house when I was small. She had been widowed at 36 when her husband—also 36, a doctor and army captain who had served the British on the frontlines in Egypt and Palestine during World War I and who returned home because he was suffering from what they called “shell shock.” He died soon after. Before that they had lost a five-year old girl child to diphtheria.

After her husband’s death, Hannah brought up three young sons on a small Government pension, with the help of her highly educated siblings and some money she got by selling her jewelry. Her youngest, my father Solomon the marine engineer, was the son she spent most of her years with. She lived with us till she died. It was she who made this sharbath almost every Friday morning. Later it was my mother who made it. But we made it less and less often, as

we grew up and homework and endless extra classes and tests took over, and my mother had less and less time, and we did not help her much either. Later, years after I was married and my husband and I moved to the US, I made sharbath for the very first time on my very own, mostly from some tips from my aged mother and from snippets of childhood memories.

–

I am a small child. It is Kolkata in the late 1960s. I would get in the way, trip my silver-haired grandmother up by getting entangled in her sari, but she would never shoo me away. The dusty raisins (that sometimes looked like those ugly pig ticks to me) were obsessively picked over, de-stemmed, washed thoroughly, and soaked in water in a stainless steel dish. Covered and left to soak in the corner of the kitchen. Like bread, it sat to brood, but instead of rising like a cloud, the raisins plumped up, turned as fat as the seven fat cows that good old Joseph the Dreamer saw in his vision. (As a child I thought Joseph was so handsome—at least, he was handsome on the cover of my Ladybird book). I hovered around the swelling raisins, peeking under the lid of the dish to report progress. I was waiting for the next step.

When I was a teenager, still dealing with the loss of my grandmother, I understood for the first time what caregivers of the aged and dying went through. I came face to face with death, the

death of a loved one at home. And the rituals, (just simple ones as we weren’t religious and did not know the prayers), the funeral, and the trauma of it all.

During the a year or so after my grandmother’s death, I was probably depressed, though no one, including myself, knew it. When we made sharbath, I missed my grandma, and nothing gave me joy. Not even Friday sharbath. But some years later, something happened that lightened things up a little for me. And it had to do with raisins.

We were preparing for Yom Kippur, and we often prepped the raisins a few days in advance. About a half kilo of raisins and been meticulously picked over, washed, and drained by my mother. Then she had laid them out to dry, as she often did with rinsed vegetables and fruit, on a tea towel resting in a bamboo souk—a woven wicker tray in which rice (or grain) is threshed to remove chaff and stones. That day she placed a low stool in the bright sunlight that filled our gorgeous verandah, and she put the souk on it. She spread the dark damp gems out with her fingers to make sure they were in a single layer and would dry quickly.

A couple of hours later, the raisins had disappeared. We all came to look for them, amazed at this strange disappearance. It’s the damn crows was the general consensus. The crows were always stealing things, always hanging about our windows. They got scraps from us all the time. Some of them we knew quite well. And now they were getting bolder. Perhaps it was a stray cat or two, or even a couple of those huge hairy rats—they could have sneaked in through the kitchen window in the afternoon when everyone was napping after lunch. Perhaps the window had been left ajar by mistake? Or the creatures had climbed through the railings of our second floor verandah in broad daylight?

The next morning we discovered that our dog, Goofy, was acting strange. He wobbled and weaved as he walked. Then he got “sick as a dog” indeed. No one had given him a thought. It would have been easy for him to stand on his hind legs, for his shaggy face to reach the raisins and swallow a souk-full of them in a few gulps. The puzzle was solved. The culprit? A gluttonous Silky Sidney terrier with a bellyful of fast-swelling raisins! The poor fellow threw up and defecated everywhere. I’ll say no more. But we laughed and laughed. To this day we remember and laugh: deep belly laughs. And so that story ends.

–

Let’s start again. With a fresh kilo of raisins. Cleaned and washed till they glisten. Then soaked. Then strained, put into a dekchi, covered with water and set to boil on the gas stove.

The raisins roll in their own juices in the darkening water. Then they simmer slowly till the froth rises up all frizzy and curly like my hair. Then Granny turns the stove off, takes the dekchi off the heat, covers it. Patting my hair, she says, “Let it cool.” Agony. Wait, wait, wait. Was this what adult life was all about? A good lesson learned early.

Soon enough, it is time to strain the almost-purple liquid, smash the pulp and squeeze the last drops of juice out. And make sure no seeds escaped. Now, again, I think of the figure of Autumn in Keats’ poem, slow and almost intoxicated with the fumes emanating from the apples being pressed. The juice oozing, her eyes drooping. Her mind lost in dreams. I become this sleepy, dreamy girl. When I open my eyes I can’t see the people I knew. The scenes around me have changed too.

Draksha-cha sharbath. Raisin or kishmish sherbet. Or angoor ka ras. Or whatever it may be called in your community. Our homemade sharbath made from special grapes called sultanas. Dried grapes as long as the first section of your index finger, grapes with large pips that had originated in the Middle East and were brought to India by Afghani and Kashmiri merchants, who sold them to us in New Market. Long live the vineyards and long live the hands that grew these grapes, that protected them and tended them, that picked them and dried them, that endured endless hardships, the hands that brought them to our land, sometimes through dangerous and difficult terrain, through rocky paths and mountain passes, to our markets all over India.

Long live draksha-cha sharbath. Long live the hands prepared the sharbath. We poured the sharbath into small glasses—whiskey shot glasses from Scotland with each one bearing a pastoral scene, bought by my marine engineer father on one of his voyages. Kept pouring till the sharbath spilled over into the saucers below, to symbolise abundance, blessing. Like in King David’s psalm. We said barakha together, drank from the exquisite glasses, and then from the saucer. This is our harvest I carry with me. My cup runneth over.

……………..

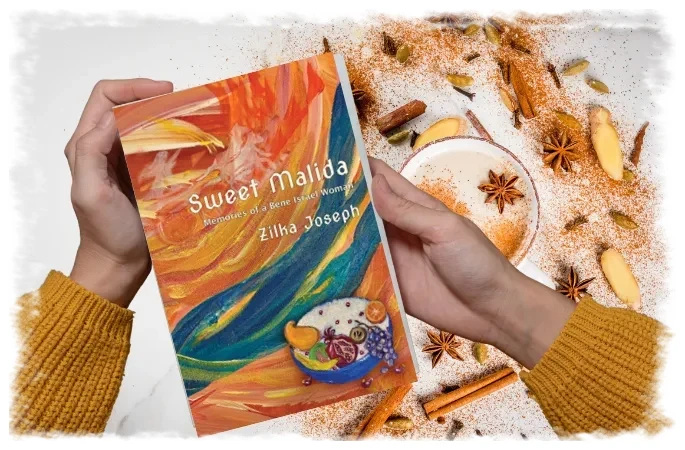

Excerpted from Sweet Malida: Memories of a Bene Israel Woman by Zilka Joseph. Copyright © 2024 Mayapple Press. Reprinted with permission from Mayapple Press. Woodstock, NY. All rights reserved.

We are excited to introduce Zilka Joseph, a poet whose work spans Indian and Western cultural influences, drawing deeply from her Bene Israel heritage. Her latest book, Sweet Malida: Memories of a Bene Israel Woman, is a poetic exploration of memory, tradition, and the delicate layers of belonging. Released on February 27, 2024, this collection invites readers into the sensory and emotional heart of the Bene Israel community, weaving personal memories with the heritage of a dwindling culture. In Sweet Malida, Joseph’s vivid poems bring to life the flavours, rituals, and longings of her past, reflecting on themes that resonate with readers interested in diaspora, identity, and the preservation of tradition. Acclaimed by literary voices for its richness and emotional depth, this book captures a universal experience of memory and identity. Zilka Joseph has been widely published and celebrated for her contributions to poetry, including previous works that were Foreword INDIES Prize finalists. We are thrilled to share her evocative voice with FemAsia readers.

Mayapple Press is a small literary press founded in 1978 by poet and editor Judith Kerman. We celebrate

literature that is both challenging and accessible: poetry that transcends the categories of “mainstream” and”avant-garde”; women’s writing; the Great Lakes/Northeastern culture; the recent immigrant experience; poetry in translation; science fiction poetry.