I always tell her she is very brave. Maybe I should use the word ‘courage’ more often.

“You know I left you behind because I had to. I feel bad about it.” Ma said.

“Don’t. Momma you did what you thought was best for me,” I said.

In my head I added, “Ma, you were barely 30 and making tough calls.” I meant every word of it. What she did required courage. A lot of it.

Mum and I had this chat in 2019 in my Noida flat, a day before my book release. She gifted me a handwritten letter. She gave me the letter— written on a note book page and stuck in a two-fold maroon wedding card, the types made of recycled paper—albeit a little shy. “Papa always writes poems. I have written a letter,” she said.

I was amazed at the effort and the idea. I went to my room to read it. Alone.

By the end of it, I had tears in my eyes and a sob in my voice. I went back to her room and hugged her tightly. She let me. She isn’t the ‘hugging types’. But I guess she could feel the acceptance of her decision and her confession in my hug. Dad was sitting right there unsure of what ‘exactly’ was unfolding before him. The chat had followed the hug.

Why hadn’t I conveyed this ‘acceptance’ till now. I had never thought otherwise. NEVER.

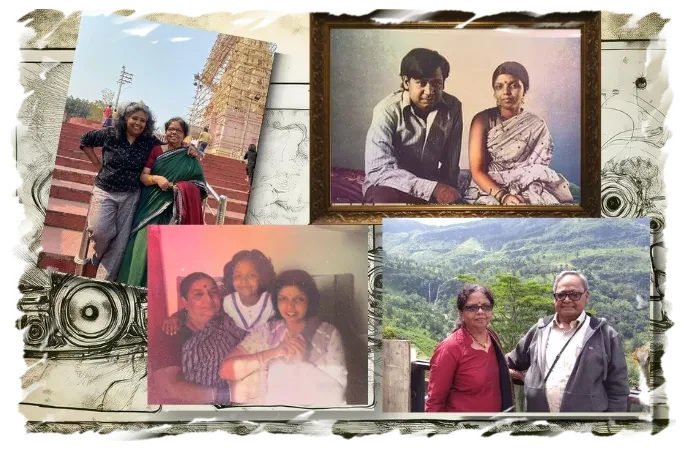

The incident goes back to 1984 when dad had a kidney failure. She was only 29—seven years of marriage and a five year old child. Dad’s illness came like a tornado sweeping my parents off from one hospital to another. First, Chandigarh. Then, Calcutta. And finally, Vellore. Mum needed to pay complete attention to dad and I was too young to be left behind. Both the families rallied around her. In different ways.

Nani was the back up. A solid backup. Both of these women were like Durga and Kali.

Despite everything going on with dad, ma never once lost focus of my education. Bala Bhavan School in Vellore was stop gap. The real deal was in Jamshedpur. After all, she had agreed to marry dad because Jamshedpur had good schools!

I joined Little Flower School in KG mid-year. My parents were back after the first transplant. Dad’s older brother, our Poppins Chacha, had donated his kidney. It was a brief stay though. Almost a year later, his kidney failed again. The transplant hadn’t worked.

He had to be rushed to Vellore but she was determined that I had to continue school. It would either have to be Nani or someone else. But Nani was needed there. Our old neighbours—the Chandran’s, a Malayali family with a son a couple of years older than me—offered to keep me. I was a friendly child, I could stay with anybody. I was very fond of uncle and aunty and they of me. The son, not so much—that feeling was mutual.

I was too young to grasp the gravity of the situation. But I remember her coming to the room and asking me if I would be ok. She also clicked a photograph of me before leaving. I was wearing yellow, I think she was wearing yellow too. I told her I will be OK. She must have been distraught but she had to focus on dad.

The second transplant, finding a donor, keeping him alive was going to be tough. Once again the families rallied around.

The doctors had given dad 10 years and not very great 10 years at that. When I look at her now, I don’t think she would have given a second thought to this 10-year- deadline. She was confident that nothing would happen to dad. She soldiered on. And dad lived for the next 39 years.

She might roll her eyes at the ‘F’ word but I totally believe that she had/has a very “Fuck-You-and-Fuck-off” attitude.

Dad’s second donor was Bhola from Benaras. On the day before the surgery, he refused to meet the doctor because he wanted more money. Though the Tata’s took care of my dad’s entire treatment and our stay, there was only so much money that could be offered.

My dad’s nephews (about the same age as dad) came to mum a little worried about Bhola. Ma walked up to him—Bhola was drinking chai just outside the hospital gate— and said “I don’t care what you want now, you won’t get it. You are coming with me to the doctor, right away”.

The nonchalance in her voice can be very persuasive. Very Godfather-like. She waited till he finished his chai. The second transplant was a success.

“Obviously, there were moments when I thought I couldn’t take it any more. I almost got off the train at one of the nondescript stations in Orissa. I just wanted to leave the two of you.” We have laughed about this.

The six months I was at Chandran’s I received letters regularly from dad and mum. When Leela aunty told her I had got highest in some subject, English I think, Ma was a little worried. “I don’t want any pressure on her. I just want her to be in school. Marks don’t matter.” I was in no pressure. I never have been. I realised much later in life that the reason was Ma’s guilt of leaving her child behind.

If all this isn’t courage I don’t know what is. I have never told her this. Maybe I should. But I always tell her she is brave. VERY BRAVE.

She was brave to let her 11 year old cycle to the market to buy grocery. Or, just cycle on the main road.

She was brave to make an even younger me climb over the railing on to the parapet of our second floor balcony to pluck chilies, that grew by sheer accident. Hand to heart, I felt like Amitabh Bachchan and I don’t regret a moment of it. But had I slipped, I would have landed on concrete.

We laugh about how in this day and age, someone would have made a video and she would have trended on twitter with the hashtag #KaisiHaiYehMa.

“You were the only help I had and so I made you run around,” she smiles. Now I am very certain that the ‘I-can-do-anything-in-this-world’ attitude was seeded during those chilly-plucking escapades!

I know she did the best for me and she—my mum, ma, momma, amme— was the best thing to happen to dad. The only hashtag that comes to my mind is #MaHoTohAisi.

This work was written during the Ochre Sky Memoir writing workshop facilitated by Natasha Badhwar and Raju Tai.