For those who have read Elizabeth Strout’s earlier nine novels, reading Tell Me Everything feels like reconnecting with old friends. We know not just what happened in their lives but also what goes on inside their heads: their inner lives, yes, but also their hidden lives. Two different entities, aren’t they? We are proud of our inner lives, consisting of feelings, opinions, understandings, even allowing imagination. Our hidden lives, on the other hand, contain what we want to forget, what we do not want others to know. Strout dares to reveal that hidden lives are not only about the bad things that happened to us but, more terribly, about the harm we have done to others. Those of us who are fans of Olive Kitteridge know what she did to her daughter-in-law’s sweater, for example. I do not want to reveal more, in the interest of those who have yet to meet Olive.

Instead of diving into plot details (do Strout’s novels have a plot? If they do, does it matter?), let’s address the question many friends of mine, who somehow thought Tell Me Everything would summarise or resolve the previous novels, have asked.

Is it necessary to have read the previous books to enjoy Tell Me Everything?

Definitely not. The obvious reason is that the writer provides details about relevant incidents from the earlier books. Yet Strout’s process is much greater than that. I do not know how she achieves that seemingly effortless way of making all readers feel welcome in the world she presents in this book. The reader who has met Lucy, Olive, William, and Bob earlier is happy to meet old friends. Sometimes, readers are even relieved to find that, in this book or in the time that has passed between stories, some character they were concerned about has received the succor, redemption, courage, or closure they needed so badly, though the earlier stories were ambiguous about whether they received it.

For example, let’s go back to her first novel. Amy’s feelings for her mother fluctuated between “…the sound of her mother’s car turning into the gravelly driveway. It was alright. Her mother was home,” and, in Strout’s very next sentence, “And yet, the actual presence of her mother provided disappointment—the small anxious eyes as she came through the door, the pale hand flittering to tuck up the brown strands of hair that escaped from the tired French twist.” A tired French twist, an unlikely adjective, possible only in this most intimate of all relationships, full of criticism, full of love.

And Isabelle feared not only Amy’s hatred but also “her daughter’s pity for her ignorance.” And yet, “(It was) awful to wonder, had she always frightened Amy?” The book has shown us that she did frighten and scar Amy in that one brutal moment of anger when she cut off her daughter’s most beautiful feature, her hair. Strout mentions earlier in the book how Amy inherited that gorgeous hair from her father, the man who abandoned this mother-daughter duo. Also, we know that Isabelle has been upset at Amy’s continued defence of Mr Robertson, the man who violated the teacher-student relationship by taking advantage of a child’s feelings for him and sexually exploiting Amy. Isabelle probably sees this as a repetition of her own past, and of course, the kind of attachment that Amy feels for this middle-aged teacher is also because of her father’s absence. So, the anger has multiple aspects, all entangled with each other and the past, and so, despite Amy’s “No, Mommy” pleas, the shears have disfigured the child, and later Isabelle’s “Clean up that mess” has sealed that event with extreme hatred.

It is with this hatred in place that the mother and daughter part at the end of the novel, with Isabelle wishing “…she had spoken, had told the girl she loved her.” The girl, Amy, only a while earlier, in answer to her mother’s question, “Are you hungry, Amy? Would you like something to eat?” had simply shaken her head, a gesture that Isabelle saw “as proof that already the girl had been lost to her; already Isabelle’s basic attempts to mother (for what was more basic than feeding?) were being dismissed; already the girl felt herself handed over; already the girl was ready to go.” But Amy had simply shaken her head because she was “not able to speak because of some swift, unarticulated compassion for her mother.” These tiny exchanges in that intense but irritating, toxic yet nurturing relationship. Tiny, shattering exchanges. Did Amy and Isabelle talk to each other again? It is so easy for mothers and daughters to become estranged.

Now, after a quarter of a century, Elizabeth Strout reassures us that they made it. Never one to sentimentalise, Strout conveys their news in Tell Me Everything through that matter-of-fact, even rude (often called cantankerous) but lovely woman—Olive Kitteridge. It is Olive who says, “Amy Goodrow, Isabelle’s daughter, was some high muckety-muck doctor and apparently Amy and her husband had decided to have Isabelle come live in a facility near where they lived.” We are glad to hear that these two made it.

A fleeting mention of her husband, Dr. Arjun, helping heal trauma caused by the Math teacher, and an invitation to her mother to live close by provide a kind of closure. Again, Strout avoids a too-happy “all is well” ending by granting Isabelle the agency to say, “I just told them finally… ‘I’m not going,’ Maine has been my home since you were a baby.” This, too, is reassuring, as Isabelle’s reason for staying is her irreplaceable friendship with Olive: “I have my friend Olive, who I will never be able to replace.” That fierce Olive for a friend! What more could we muckety-mucks want for Isabelle?

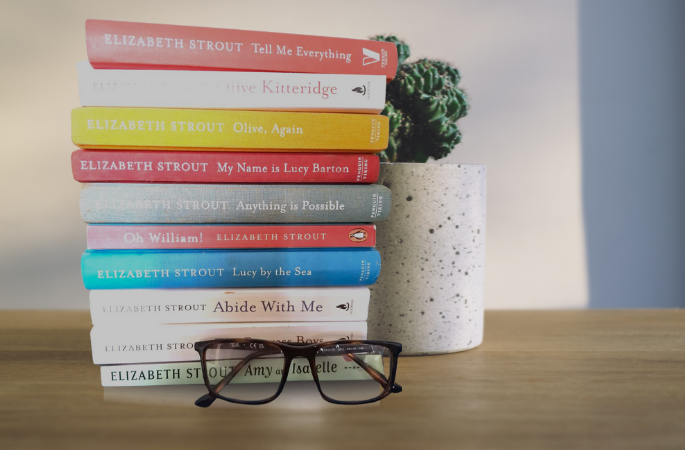

I hope that answers the question. No, it is not necessary to have read the previous novels, but for those who have, new adventures are enhanced by the pleasure of recollection. A more important question is whether readers, after visiting the world Strout creates in Tell Me Everything, will want to read her previous novels. I think it’s very likely. I envy you if you are at the beginning of what will be a most rewarding journey.

You will gradually discover more about the characters you met in this latest novel. Each new revelation enriches the experience, giving readers the added advantage of knowing where the characters are now. Although this book made complete sense on its own, knowing certain things left unrevealed about the characters will make reading even more satisfying. For instance, Tell Me Everything reveals much about Bob Burgess (Strout’s working title was The Book of Bob!), and reading The Burgess Boys may deepen understanding of why Bob will never act on his feelings for Lucy, why he is what she calls him in the latest book—a “Sin Eater.” This latest novel is not a summary or culmination (I certainly hope it isn’t), but it will evoke a smile when, for example, at the end of the first chapter of My Name is Lucy Barton, Lucy’s mother, taking a break from sharing her observations and stories, says, “Oh Wizzle-dee, you need your rest,” and Lucy replies, “I am resting! Please, Mom. Tell me something. Tell me anything…”

As someone engaged with every word Elizabeth Strout has written, I returned to My Name is Lucy Barton with a thrill.

Strout’s novels honour the lives of ordinary people, showing the richness and layers of their stories. She is deeply interested in all her characters. And in writing, she speaks to them and perhaps also to us, her readers, telling us that we exist and that our lives have consequence. Her famous “Oh” is her way of saying, “Oh, your small action made a difference to this person,” “Oh, even if you decided not to turn your friendship into something more, I see how well you understand each other. Move apart, but not before knowing this,” “Oh, you may not be able to express what you feel about your child, but one day she will know you loved her,” “Oh, you may have been a strict teacher, but many students remember your kindness,” “Oh, your love may have been unrequited, but I know you had the capacity to adore a person; you loved deeply, and so, I am writing you a love story,” “All of us feel those fears of death, anxieties about health. Oh, just breathe.”

Stories carry meaning, and sometimes they create it. Knowing that Elizabeth Strout wrote ten novels about lives as ordinary as mine makes my life feel meaningful and, therefore, bearable. That is immense.

Ten years ago, during the Olive Kitteridge tour, Strout shared that she writes for those who need her stories, trusting they will find them. Judging by the immense popularity of her books, it seems many of us indeed have.