‘I was her friend even before I was born.’ This thought raced in my young mind as my mother, and I crept silently to Lily’s mother’s room. The room was huge, with a high ceiling and windows with ledges and ornate grills. There sat Jha Aunty, dwarfed in her huge four-poster ancestral bed. She had a taanth cotton saree wrapped around her, her eyes looked here and there, and her red vermilion shone like a knife.

‘O God, I hope she is not dead.’ My mother sat gingerly on the bed while I, only 21, stood unsteadily beside her. ‘Bhabiji’, my mother spoke, and Jha Aunty burst into tears that refused to be damned. All I could hear was’ Lily, lily.’

My mind wandered off. I noticed Society, Savvy, and Reader Digest magazines. It was the early nineties. As I flicked through the magazine pages, I contemplated that no one called our mother’s name except for our fathers. Nasreen and Kiran, for all practical purposes, were Mrs Rahman and Mrs Jha in the dusty coalfield town of Asansol in West Bengal, where the mighty river Damodar passed through. This is where a dam was built in 1952, yet our mothers were known only by this surname.

Lily was my brother’s friend. She was three years older than me. They had started their school together. Our father worked in the far-off China kauri mines, and our mothers became friends drawn together by their similar lilting Bihari dialect.

She and I went to the same Christian school. At the AG church school, we sometimes bumped into each other in the red brick-lined building. But apart from a smile exchanged, we hardly talked. In school, you see that the three-year gap is enormous. It is like the Damodar river in spate, which you could not cross except when helped by someone. We both had our school groups. Our fathers got transferred to different coal mines, but the school remained the same and was the nucleus of our life.

In those days, the early eighties, the phone was a rarity, so sometimes my mother would write a note to her friend, Jha Aunty and ask me to give it to her. Once the letter got smudged because of rain. I carefully took out the crumpled letter and copied it on fresh paper; I began to write ‘Namaste Bhabhiji’ and gave the letter to Lily after copying it. It became family folklore how, in class 4, I copied the exact words and did not convey the message outright. Both our families had a hearty laugh over my bewildered heart. Lily was in class 7, and I was in class 4.

Suddenly, Bhaiyya and Lily grew up and took board exams, and they moved to Calcutta for class XI as our town, Asansol, did not have a proper English School beyond 10. Bhaiya got admitted to La Martinere and Lily in Shikshaten school in Calcutta. I resolved to follow them there for three years. However, soon, news came floating in. Lily failed her science exam in class XI, changed her subject to the commerce stream, and failed to clear it again. She had wanted to do arts, but her father, IIT-educated, refused to entertain this thought. Again, she flunked the exam; now, her weary parents allowed her to study subjects labelled as the Arts stream. Sitting 200 km away from Lily in Asansol, this was my first brush with the drama around humanities subjects. In the late eighties and early nineties or even today, science subjects are supposed to be the default choice towards a better future, ignoring the children’s inclination. True to form, I opted for science in class XI even though my marks were just above average. I never asked myself what I was good at. I just followed my brother and Lily. And yes, I could not go to Calcutta- marks dictated that I went to Aligarh Muslim University in Uttar Pradesh.

We were thousands of miles away, and sometimes we met on holidays- she had joined Shantiniketan in West Bengal, and I was still in Aligarh. We exchanged news, but we were on each other’s periphery. ‘Qutub Minar dikhta hain, can you see it from your Hostel?’ I had asked Lily once when she returned to the distant Jhanjhra – an Indian and Soviet Union Colliery for her holidays. She had cleared the entrance exam for Master’s in Social Work at Delhi University. It was a dream for me – Delhi seemed like a place where dreams were fulfilled. Even though Aligarh was nearer to Delhi, in my mind, I was still a small-town girl from West Bengal.

As my mother comforted Jha Aunty, I sat terrified and caught snippets of their conversation. Lily had married someone of her own choice. He was a tribal classmate. We were on the cusp of change as a society, but parents were on another level. Jha Uncle had barred Lily from coming home, and Aunty could do nothing except cry.

Fast forward to 5 years, Lily was called home once she had a baby girl. I remember watching her and her baby in a white frilly frock, fascinated. The husband was nowhere to be seen. She had come to attend Bhaiya’s reception, and we hardly talked as I was running around looking after guests. It was 1998, and I still have her mandatory picture with newlyweds, my brother and sister-in-law.

Cut to 2005, I am in Delhi, married with a small child. I know through the grapevine that Lily is in Delhi, too. I get her number through a circuitous route. She is now a central govrment employee with 2 children. We visit each other once or twice at our kid’s birthday parties.

Then, silence again. We are both busy with the business of life. We are friends with each other on Facebook. I see her updates, and sometimes she comments on mine.

It is 2013. A notification drops in my message box. It is Lily’s sister-in-law. She tells me Lily has changed her number. I call the number, and it is just like yesterday. I hear a silence that reminds me of her mother’s shock years ago. I drag my reluctant husband and kids to meet her in Pitampura.

We meet in a mall. Her husband has left her, and she is bewildered. ‘Why did he do this -tum batao, kya hua, don’t husband and wife fight?’

It is 2015, and she is in our lawyer’s office. She shows us the white accusatory notice of divorce. Her tears fall on her dupatta. Her father was right about her husband; that is her constant refrain. She does not want to contest the divorce petition. I try to convince her otherwise, and I try to call her daily. Some days she calls me twice.

It is 2016, the first day of contesting her divorce petition. She holds my hand as we walk into the family courts of Rohini. She is wearing a red lipstick. I think of our mothers; it took them a lifetime to call each other by name. Kiran and Nasreen’s friendship has evolved in our friendship: Lily and Shinnu. It is a solid fifty years of friendship.

Female friendship surprises you with its tenacity and preciousness. They are the ones that hold us while everything falls apart. They don’t need long explanations. They understand our silence, too. They know you and accept you for what you are.

It is 2018- she calls me and says sorry for the rising hate crimes in India. We console each other. She tells me a story from when I was not born. My grandfather, along with my parents, had gone to her home for a visit. They had stayed overnight because of torrential rains. Her grandfather, an orthodox Brahmin man was there too. In the evening, they both offered invocation to their Gods side-by-side; one chanted Sanskrit prayers and the other offered Namaz.

She has become my memory keeper as I have of her. We both continue wearing red lipstick.

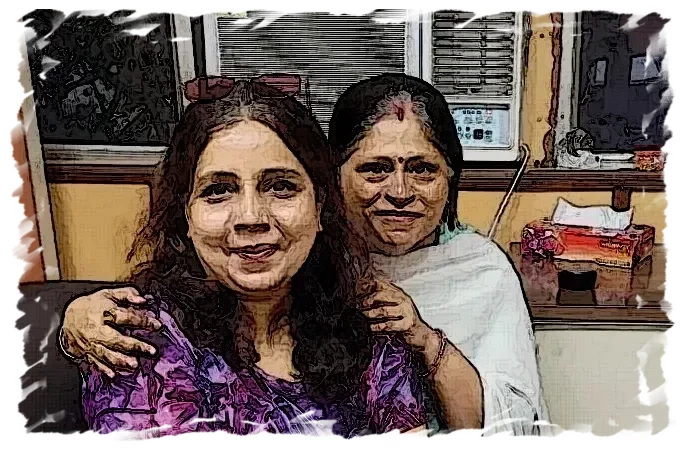

*Above photo is us, in Lily’s office in 2023. We both call each other by our pet names.

Farah wrote this essay in the Ochre Sky Memoir writing workshop facilitated by Natasha Badhwar and Raju Tai.