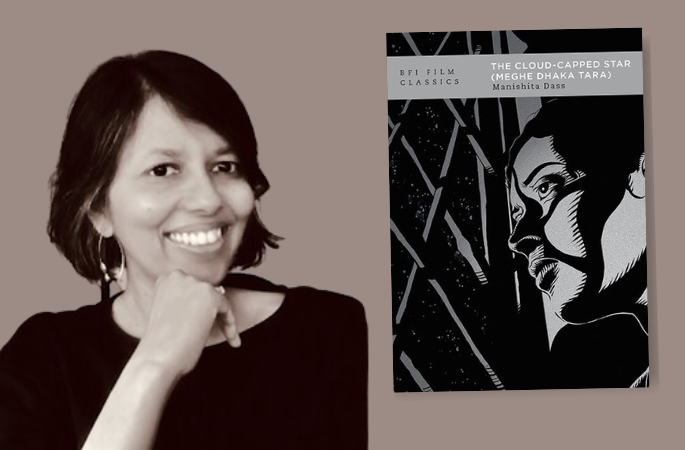

Manishita Dass, The Cloud-Capped Star [Meghe Dhaka Tara]. London: BFI, 2020.

Ritwik Ghatak and His Cinematic Theatricality:

Realism and Melodrama, Myth and Melancholy, Aesthetics and Politics

Cinematic Theatricality

Manishita Dass’s poignant, poetic and magisterial BFI (Classics series) monograph, The Cloud-Capped Star [Meghe Dhaka Tara], 2020), argues convincingly for Meghe Dhaka Tara‘s (1960) specificity as lying in its cinematic theatricality, which the author defines as “an ensemble of visual and aural effects evoking the artifice of and drama of theatrical performance” which is at the same time “intensely cinematic. It is “‘a mode of address and display'” which has its provenance in the “creative collision between the stage and the screen, between Ghatak’s ideas about the film form (partly shaped by Calcutta’s incipient film society movement of the 1940s) and his experience as an activist in the leftist theatre movement of the late 1940s to the early 1950s” (p. 9). For Dass, “the unsettling power” of Meghe Dhaka Tara lies in its cinematic theatricality.

In the corpus of Ghatak scholarship, this is a significant intervention by the author whose earlier essays include “Unsettling Images: Cinematic Theatricality in Ritwik Ghatak’s Films” (Screen, 58:1, Spring 2017) and “The Cloud-Capped Star: Ritwik Ghatak on the Horizon of Global Art Cinema” (in Global Art Cinema: New Theories and Histories, ed. Rosalind Galt and Karl Schoonover, Oxford University Press, 2010), and whose investment in the Left ideology driven Indian People’s Theatre Association is well known, along with her undermining of the auteur theory by arguing for the co-authorship of significant team members, including that of female actors, and acknowledging the collaborative work of a multiplicity of artists/technicians in cinema, which is a collective effort. For instance, the contributions of the music director (and sound designer) Jyotirindra Maitra in Meghe Dhaka Tara. Supriya Chaudhuri as Neeta, the iconic protagonist, haunts the monograph as she did with the Ghatakian imaginaries, straddling the mythical universe of Durga and Uma and the next-door neighbouring girl, who while providing for the sustenance of her displaced middle-class family burns out of breath/lungs due to consumption.

Cinema and Theatre

Quoting veterans Bijon Bhattacharya and Utpal Dutt, who had worked with Ghatak in the IPTA, the author informs us how they felt “Ghatak’s imagination found its most effective expression on film, [as] his aesthetic of exaggeration was perhaps better suited to the cinema than to the theatre.”

We do not have sufficient information about Ghatak’s actual practice as a theatre director to assess the comparative strengths of his cinematic and theatrical practice. However, the evidence of his films implies an organic connection between the two. The unsettling power of his films emerged out of the fusion of theatrical and cinematic forms – more specifically, out of productive friction between an aesthetic of distance and artifice traditionally associated with the stage and an aesthetic of intimacy and naturalism predicated on the cinema’s ‘appeal of a presence and proximity’. (pp. 78-79).

Ghatak’s profound reflections on theatre and cinema speak of his genius as a film theorist. He contrasts the constant distance from a fixed point of view in theatre to the proximity (as well as distance) available through technology in cinema. Dinen Gupta and his actors talk about how meticulous he was in using lenses. The author has done yeoman service by painstakingly translating many significant passages from articles and interviews, including that of Ghatak, from the original in Bengali. [Please see the book’s detailed Notes section (pp. 98-101) for the many rare Bengali source materials.]

Of course, the discourse surrounding Cinema and Theatre has a long history regarding their hierarchies in art history; for instance, the low-culture “nickel and dime” cinema had to validate itself by clinging onto its similarities with the high-culture elitist theatre in its early decades, and possibilities in their form. Consider Tarkovsky and his (conflictual) search for what could be theatre in cinema, for instance, Andrei Rublev (1966). Or, for that matter, Mani Kaul’s Ashad Ka Ek Din (1971). The other extreme is populated by diverse artists like Peter Brooks and Fassbinder, who straddled theatre and cinema. Think of the distance as well as the proximity in Fassbinder’s adaptation of Ibsen’s Doll’s House (Nora Helmer, 1974), wherein the several mirrors in the mid-long shots enable the closer view in the same frame. Similarly, when the immortal Satyajit Ray tried to pay homage to Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People (Ganashatru, 1989), he was criticized for being theatrical/static. Ghatak’s engagement with dramatic elements cinematically marks his singularity, and the author has kept the focus on this unique trait––his investment in sounds and images, which were pregnant with the theatre of life/emotions of the marginalized.

Image as the Provenance

Regarding Ghatak’s densely layered cinematic universe and Meghe Dhaka Tara in particular, the author questions the general tendency to subsume his films, particularly his aesthetics as predicated on melodrama and excess by focusing on realism in the film, for instance, in the way the constructed set of the protagonist Neeta’s home was modelled on the photographs of an actual such refugee colony (p. 60). This naturalism is complimented by the realism of shooting on locales for the grocery shop in the nearby street. The realist mode in framing the quotidian life and times of Neeta and her family members is then juxtaposed with highly dramatic moments, both aurally and visually, albeit in a cinematic way. The Indian cinema scholar and Ritwik Ghatak specialist Manishita Dass, thus, contributes to the rich discourse surrounding Ghatak by deconstructing his predilection for excess, regarding his preoccupation with Jungian archetypes, mythology, particularly of the mother (Durga) and daughter (Uma) figure in this case, and melodrama, by shedding light on the cinematic use of images and sounds. More importantly, the melos-driven Ghatak’s narrative universe straddles from the astute use of a classic raga-like Hamsadhdhwani to poignant rearticulation of folk songs and the in-between pensive foray into the (lieder/poems set to) music of Rabindranath Tagore–Rabindra Sangeeth (pp. 47-51). The author has done a meticulous textual reading of the images, as inspired/provoked by the music and exemplified/illustrated by the excellent/painstaking screengrabs in the book, to illuminate us on the uniqueness of Ghatak’s vision and cinematic genius, validating his claim regarding why Meghe Dhaka Tara is the best among his works, and its protagonist Neeta most close to his heart, as quoted by him and cited by the author (p. 45). In “A Face in the Crowd,” the third chapter, we get the image that inspired Ghatak:

A young woman carrying a sheaf of papers and a bag, a very ordinary young woman, tired after a hard day’s work, often waits at the bus or tram stop near my house. Her wavy hair creates a halo around her face and head, some of it damply clinging to her forehead. I see history in the fine lines of pain on her face, and my imagination takes me into the very ordinary yet unforgettable drama of a life that is determined, unshakeable yet gentle, sensitive, and marked by infinite endurance (p. 21).

The details of her hair while creating a halo also “damply clinging to her forehead,” and “the history in the fine lines of pain,” as the author points out, informs us of the epic theatre of the quotidian in the Ghatakian universe, wherein “ordinary” is “unforgettable” and “sensitive” coexists with “infinite endurance,” as emblematized by the tenderhearted but resilient Neeta who burns like a candle for her family. More importantly, the author gives insight into how Meghe Dhaka Tara affected her, particularly as a Bengali teenager/woman. She details how the unfulfilled hopes and crushed ambitions of a generation of uprooted Bengalis “caught in the crossfire of history” are evoked by Neeta’s final, unforgettable scream of agony, particularly for those familiar with the historical and cultural context of the movie, like her. Because her parents and some of her closest family friends belonged to the generation, who had witnessed firsthand the impact of the Partition (of Bengal), she did not view Neeta’s scream as a historical abstraction the way non-Bengalis might have perceived it, as exemplified by the discourse on Ghatak and his melodramatic excess. The narrative of Neeta’s endless suffering reminded the author of the lives of two of her favourite aunts—one of her mother’s closest friends and mother’s older sister—when she “saw Meghe Dhaka Tara for the first time in her teens” (p. 2).

They were forced to pursue job-oriented higher education by their liberal middle-class family and had to give up their aspirations to become historians and economists to take care of their families in the wake of the Partition, and their father’s passing away. They never married and spent their golden years in a rented apartment because, despite leading a frugal lifestyle, they could not accumulate enough savings to afford the security of a home of their own. They worked as schoolteachers while paying for their college education, raising their younger siblings, and caring for them until retirement. However, unlike Neeta of Meghe Dhaka Tara, they lived long lives, “translating their left-liberal and proto-feminist principles into everyday practice, had a formative impact on” her (pp. 2-3).

Of course above is a paraphrasing of the author’s heartfelt recounting of the personal as it has inflected the political regarding her engagement with Ghatak as driven both by the trauma of Partition and displacement and the subsequent inclusivity/ubiquity of “Bangal”––the people of East Bengal within Bengal (Calcutta) and left-oriented IPTA and its philosophy of art for people’s sake, as emblematized by Ghatak’s words: “all art ends in poetry, a poetry drenched with the sweat of the woes and troubles of working people” (p. 23). If the provenance is in the image of the halo around a young woman’s face and head and some of her hair “damply clinging to her forehead,” the film is bookended by the distinct but quotidian image, punctuating the author’s assertion of Ghatak’s commitment to the reality on the ground and the predicament of displaced and marginalized people, of the torn slippers of a working woman, of Neeta at the beginning, as she bends down and looks at the loose toe-thong, a common feature in the case of worn-out sandals, and takes the sandals in her hands and starts walking bare feet.

Art, Poetry, Torn Slipper/Working-class Woes

The author points to Ghatak’s dense engagement with music as influencing his storytelling and draws parallels between the form of a raga and the narrative structure of Meghe Dhaka Tara: “slow, unmetered exposition (alaap) that establishes the melodic contours of the raga and then moves into a more expansive, rhythmic mode, gradually increasing in tempo to reach an impassioned climax before subsiding into silence” (p. 46). In Meghe Dhaka Tara too, Ghatak initially weaves Neeta’s quotidian life like an alaap, with the many layers of a middle-class home, in an overcast light due to displacement, foreshadowing the tenuousness of security through the motif of the “torn slipper,” albeit with the solace of music, informing us of her close bond with her brother: The gesture of her stumbling on her “worn-out sandals,” kneeling, and picking them up, and walking bare feet recalls, according to the author, “Van Gogh’s painting of a pair of worn-out boots, disclose a history of toil, tenacity and economic hardship; their reappearance at the end of the film, in a poignant echo of the initial scene, will bring the collective dimension of this history to the fore” (p. 57). Additionally, posthumous recovery and fame unite Van Gogh and Ghatak, not to mention the struggles and hardships.

Continuing her profound meditations, the author details the last scene: Eventually, we see Shankar, Neeta’s musician brother, after he met her at the sanatorium for tuberculosis patients on the hills, and when he does not have an answer when the grocer Banshi asks about Neeta’s health and laments about her plight, he moves away to encounter “the image that Ghatak claimed was at the core of Meghe Dhaka Tara” (p. 91) –– in a denouement where Ghatak restages the “torn slipper’ sequence, of course now reprised by another middle-class working woman, who resembles Neeta in her built and whom we had seen earlier in the film, also when Shankar mistook her for Neeta: “She trips when her sandal breaks and bends down to examine her torn slipper, just as Neeta did in one of the first scenes of the film, and then smiles sheepishly at Shankar when he notices her looking at her and starts walking again” (p. 91). The music plays Menaka’s lament for Uma, punctuated by the frenzied “buzz of crickets that we have come to associate with impending doom” (Ibid.). The camera pauses briefly on the retreating Neeta-like figure of the woman, then cuts back to Shankar sobbing and covering his face with his hands as if to hide the “poignant visual reminder that Neeta’s tragic saga was not an isolated incident but reflected the experience of countless other young Bengali women like her and was doomed itself, time and again, right before our unseeing eyes, hidden in plain sight” (Ibid.). Such a heartfelt and scholarly reading of Ghatak’s magnum opus vindicates the author Manishita Dass’s claim regarding the film as deeply personal and specific to Bengali culture and her people while simultaneously universal in its cinematic rendering of a universe inhabited by displaced people and in its layered aesthetics surrounding a narrative of displacement and loss, and the hopes and despairs revolving around the vulnerability of the selfish/self-centred human beings, often affectionate but exploitative, and the vicissitudes of life.

Creation, Cost, and Collaboration

Persuasively arguing for Shankar as a “stand-in” for Ghatak, the author draws our attention to artists, creation, and cost, deconstructing the romantic surface to shed light on the sweat and the worn-out people/women behind it. Drawing parallels between Shankar and Ghatak as witnesses and artists, the author draws attention to the final closeup of Shankar where, he covers his face with his hands, unable to face the repetition of the reality of yet another young woman treading the tedious and gloomy path of his sister Neeta, the likeness of their journey symbolized by the worn out sandals and the rough path. While she recalls Ghatak’s adoration of Carl Dreyer and his aesthetics of closeups in The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), in the context of the closeup of Shankar at the end (Ibid.), she reminds us of Ghatak’s extolling of the childlike quality in an artist (p. 96). Shankar’s affectionate ties with his sister Neeta foreground his warmth and childlike/spontaneous quality regarding his dreams as an artist and the pursuit of music. But, as a woman from a left-liberal background who is unwilling to remove the other foot from the pedal of the ground reality, she asks us to reflect on/not forget the cost paid by Neeta/women behind such pursuits, even if it is for the cause of giving voice to the marginalized who deservedly/desperately “want to live.”

The general erasure of people behind reminds us of other crew and cast members who may not be given their due. The author sheds light on many such significant contributors to Meghe Dhaka Tara, two of them most notably: the writer Shaktipada Rajguru and music director Jyotirindra Maitra. While highlighting the flow between the mythic and the mundane, a significant aspect of Ghatak’s aesthetics, explored extensively by scholars, the author draws our attention to how the “metaphors and mythic motifs are not imposed on the every day but emerge out of it” (p. 22). The mundane is the lens to the conflict of every day as it builds exponentially––here, in this case, the history of the displaced women as they had to leave the guarded fences of their domestic sphere and move out to get educated “not to groom themselves as future brides or housewives, but rather to qualify for jobs as clerks, typists, sonographers, sales girls etc.” (as quoted in Dass, p. 23). The author elucidates how this mobility of women was in contrast to and conflict with the unchanging patriarchy and the image of the highly domesticized and ideal women/housewife at home, and the way this conflictual social conditions of a middle-class (college/working) woman was reflected in the popular culture of the time through stories of authors like Rajguru, who, though not from a displaced family claimed knowledge of it through (secondary) experience (pp. 24-28).

Indeed such details and historical contexts and anecdotes give us a glimpse of the material conditions of production not only in pointing to the source of the film as a stereotypical story, “Chenamukh” (A Familiar Face) and initially published in “Ultorath, a popular periodical specializing in film news and fiction” (p. 24), that focused on the tensions of middle-class women for its “middlebrow” mode of fiction in the 1950s and recycled the predicament of “women from refugee families negotiating changes, new roles and new forms of patriarchal control both at home and in the world outside” (Ibid.), which was ubiquitous in novels and films, like Anupama (dir. Agradoot, 1954), of those times in the late 1950s but the way the author Rajguru would play the role of being more than a writer as Ghatak’s confidante in winning over the understandably reluctant producer regarding the tragic ending he had foreseen for the film (p. 27).

Producer, Director, and Associates

[Ghatak] told [Rajguru] behind closed doors, “I had a hunch in Calcutta that this could happen – that’s why I brought you here. You’re the only person I’m telling this now: the last shot of my film will have someone like Neeta walking down a stony path in torn slippers – people like Neeta don’t die but remain part of a struggle for life. If I tell [the producers] this now, no one will understand, and the film won’t be made. That’s why I’ve brought you here, to write an episode that brings Neeta back along a trajectory that they would like. I will shoot the ending in two ways. They will understand the ‘impact’ of my preferred ending when I show it to them later but won’t get it now. So, for now, rewrite the ending according to their preference” (p. 27).

The tenuousness of climaxes, predicated on formulaic happy endings, and Ghatak’s resilience and ability to have onboard associates/confidantes come to the fore here. In fact, Rajguru, along with Surama Ghatak and the main actors, Supriya Chaudhuri and Anil Chatterjee, were the ones to vote for a tragic ending, whereas all the others sided with the producer. It makes me wonder what Ghatakda (as we, the alums from the FTII, fondly refer to him) would have shot with his cinematographer Dinen Gupta, who collaborated on three of his films. Did they have two different enactments of Neeta (Supriya Chaudhuri) stumbling on her torn slipper and taking it on her hand, and walking away in two different modes/moods, or was it going to be the retake of the same kind of shot(s)? On the one hand, you have the discourses surrounding masters, who wanted to shoot two versions of the climax, often having a valid justification, and here was visionary Ghatakda, who knew about his climax and how to “chisel” a typical middlebrow story which he did not like on his first reading, but sensed he could “express something through” it (Ibid.). Ghatak’s success as a story writer of the mainstream but sensitive Madhumati (dir. Bimal Roy, 1958) and his mentoring of Rajguru, who would later write films like Amanush (dir. Shakti Samanta, 1975) [p. 26], are essential details shedding light on collaborations across the divides of art and commercial cinema––Meghe Dhaka Tara itself a classic example of a film that blurs the border, as exemplified by its critical and commercial success, only Ghatak film to do so in history.

Cinematic Theatricality, Sound and Jyotirindra Maitra

Detailing the continuity of collaboration with some of his IPTA connections, the author foregrounds Ghatak’s productive partnership with musician-composer Jyotirindra Maitra and reliance on actors and singers like Bijon Bhattacharya, Anil Chattopadhyaya, and Debabrata Biswas (p.14). As noted by another of Ghatak’s close collaborators and composer, Bhaskar Chandavarkar, he thought all the sounds that run along with the visual track should be treated as a part of the film’s music track, including sound effects (p. 66). It explains why “the otherwise naturalistic, minimalist” film score is full of sudden, theatrical bursts of sound and music that interpret and comment on the images and sound (pp. 63-64). Thus, for Ghatak, the sound becomes a character and narrator (p.66): These bursts of sound, while interrupting the flow of the story, contextualize the domestic drama on a broader metaphorical or socio-historical level. While “the centrality of music to Meghe Dhaka Tara” is inevitable “in illuminating the subtextual level of” the film, the sound effect plays an equally indispensable “role in creating a sense of impending disaster” (66-71). However, the author notes the ubiquitous linking of “Neeta’s agony and sense of betrayal to a larger historical trauma” through “the amplified and looped sound of a whiplash” (p. 71). it subsumes the many instances of cinematic theatricality detailed by the author, particularly in the unique use of sound and exploring its theatrical potential to the full when juxtaposed with images, as possible in cinema. For example, the storm that hits Neeta when she leaves the house due to her ill health on her poor and helpless father’s emotional appeal due to the expected arrival of the child of her younger sister, who is now married to her lover Sanat, who has changed colours with time, the approval/connivance of the unchanging, exploitative mother. Ghatak defies our usual expectations of a lone, helpless woman disappearing into a desolate landscape at night. Instead, he focuses on her closeups with the sound of the storm, an uprooted tree, and its branches just outside/adjacent to the diegesis (pp. 41-43).

The author foregrounds the central role of the musician Jyotirindra Maitra in the much-discussed use of the whiplash sound in the film.

Rather than using the wails of a violin to express pain, I proposed two alternatives to Ritwik: the sound of clothes being dashed against the ground in the course of washing and the swish of a whiplash. Ritwik chose the latter. I had put the whip in his hands, but when he couldn’t get the rhythm right even in four or five takes, I took over from him. Thanks to my training in classical music, I could get the beat right (p. 72).

However, “the idea of whiplash came from ‘Madhu Banshi-r Goli’, a long Bengali poem that Maitra had written in 1943.” The “poem – an anguished reflection on the socio-economic turmoil that darkened the cityscape of wartime Calcutta, as well as a paean to revolutionary dreams of a brighter world – gained widespread popularity” (Ibid.), informing us of the ideological congruence that led these artists to IPTA.

Myth, Symbol and Reality: Invoking the Altruistic Jagaddhatri and Lamenting the Departure of Uma

… [T]here are times when a symbol can suddenly possess you, bypassing all processes of conscious reflection. You are hard-pressed to fathom its workings or connections. … So the last word in art is that old-fashioned word, the unconscious – something that is beyond the grasp of rational comprehension or language … which you will encounter, shake hands with … in your life, and those ten or twelve instants are enough for you to live. That is a genuine symbol. (Ghatak, as quoted in Dass, p. 45)

Scholars like Ashish Rajadhyaksha, Ira Bhaskar and Jisha Menon, among others, have pointed out how Ghatak’s narrative universe is inseparable from his investment in myths, particularly in films like Meghe Dhaka Tara and Subarnarekha (1965). His singularity lies in how he could seamlessly ground these myths into reality, empty them of their religiousness, address contemporary issues, and point to their complexity and denial of easy solutions. While the author acknowledges Jisha Menon’s claim regarding how “the symbolism of the benevolent mother goddess converges on the material particularity of Neeta” (as quoted in Dass, p. 31), she also sheds light on the mythic imaginaries of Ghatak as “shorn of mysticism” (as quoted by Dass, p. 12). She points out how Ira Bhaskar parallels “Neeta’s role as nurturer” and “the Hindu myth of the sacrificial fire that locates the genesis of Jagadhhatri [‘an incarnation of Durga’ (p. 31)] in the transmutation of human desires.” Like the site of havan, Neeta’s sacrifice of her desires as the provider for “the selfish demands repeatedly made on her by her mother and her younger siblings” (p. 33) from giving away the money to her siblings instead of buying new sandals to being a mute witness to her lover Sanat changing hands, are staged through scenes where the courtyard of her home plays a key role.

The author meticulously reads the trajectory of Neeta as the benevolent Jagaddhatri to the emptying of the fire of life in her by her all-consuming family to finally the elegiac and lament-filled send-off as Uma by her now successful brother and always caring and empathetic but self-loathing and helpless father who used to address her fondly as “Khuki” (the little girl, p. 59), and ma/mother (p. 39). The author’s eloquence and specificity as a Bengali enable her poetic requiem to Uma/Bengal.

In the Bengali regionalization of the myth of Siva and his wife Parvati, Parvati is reimagined as Uma, the only daughter of her parents, Giriraj (Lord of the Mountains) and Menaka, who regret giving her away in marriage to Siva. Siva features in this retelling as an irresponsible and much older husband. Uma’s parents thus constantly worry about Uma’s well-being and look forward to having her back home, even if briefly, every autumn. The autumnal festival of Durga Puja, when idols of Durga are worshipped all over Bengal for four days, celebrates Uma’s return to her parental home but is also suffused with melancholy over her imminent departure (ritualized through bisorjon or an immersion of the idol of Durga in a river) [p. 38].

The seamlessness of the mythical transformation from the benevolent Jagaddhatri to Uma is unsettled by the “studied melodeclamation,” as theorized by Bhaskar Sarkar (as quoted by Dass, p. 77), of the father. Consider, for instance, his pointing to the camera and dramatically announcing, “I accuse,” only to shirk back and quieten on his loathing self-confession: “In the past, people would marry their daughters off to dying men. They were barbarians. Today, we are educated and civilized, so we educate our daughters and then wring them dry” (pp. 39-40). After thus sucking the breath out of Uma, she now seems redundant/dispensable after “helping her family attain economic stability,” hence “leaving her free at last to leave home – not to join a husband but to meet her death” (p. 43). Subversively, as the author points out, in keeping with her feminist preoccupations from the nurturing Jgaddhatri to the tender Uma, now her journey is towards Mahakal––Lord of time or god of death (Ibid.), which could also be read as the realm of eternity, as punctuated by the pan across the mountains during the climactic moment, ending the heartrending scene at the sanatorium.

While [Neeta and Shankar] know that her tuberculosis is at an advanced stage and possibly incurable, Shankar tries to maintain a semblance of normality and to distract her with amusing details about the mischievous antics and vivaciousness of their nephew – Geeta and Sanat’s son, who is now a toddler. Neeta smiles at first but then abruptly cries out, ‘But I did want to live!’ and breaks down, clinging to her brother, beseeching him to assure her that she will live: ‘Please tell me that I’ll live, just tell me once that I’ll live!’ This is not just a cry of desperation; it is simultaneously a plea for a life worth living – a life of expansive possibilities and collective well-being beyond the confines of narrow self-interest – and, as Ghatak has claimed, a defiant assertion of Neeta’s will to live. Her voice echoes through the landscape, overlaid first by a clashing noise reminiscent of the sound of the whiplash and then by the uncanny, quasi-mechanical buzz of the crickets. As the camera leaves Neeta to pan across the surrounding mountains, her disembodied and now wordless sobs reverberate in the landscape like a wailing wind (p. 89).

Manishita Dass’s precious monograph is full of such poetic reflections on the film, living up to the expectation of one of the most committed and creative scholars on an incomparable film from one of the great and original artists/filmmakers of our times. The monograph on Meghe Dhaka Tara will be highly useful for students, scholars and researchers across disciplines. Additionally, as the author acknowledges, this labour of love is a poignant and elegant homage to a master and his masterpiece (p. 12). Fittingly, she has dedicated it to her dear, resilient and valiant aunts.

References

Banerji, Sushmita. “A cinema of partitioned subjects: Ritwik Ghatak, 1960-1974.” Dissertation. 2014.

Bhaskar, Ira. “Myth and Ritual: Ghatak’s Meghe Dhaka Tara.” Journal of Arts & Ideas. 3 (April–June 1983).

Chatterji, Shoma A. Ritwik Ghatak: The Celluloid Rebel. Rupa, 2004.

Dass, Manishita. The Cloud-Capped Star [Meghe Dhaka Tara]. London: BFI, 2020.

Ghatak, Ritwik, Ira Bhaskar et al. Ritwik Ghatak’s Partition Quartet: The Screenplays. Tulika Books, 2021.

–––, Rows and Rows of Fences: Ritwik Ghatak on Cinema. Seagull Books 2000.

Kapur, Geeta. ‘Articulating the Self into History: Ritwik Ghatak’s Jukti Takko Ar Gappo.” When Was Modernism: Essays in Contemporary Cultural Practice in India. Delhi: Tulika Books, 2000.

Manishita Dass. The Cloud-Capped Star: [Meghe Dhaka Tara] (Kindle Locations 1385-1386).

Menon, Jisha. The Performance of Nationalism: India, Pakistan, and the Memory of Partition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Rajadhyaksa, Ashish. Ritwik Ghatak: A Return to the Epic. Bombay: Screen Unit, 1982.

Rajadhyaksha, Ashish and Amrit Gangar. Eds. Ghatak: Arguments/Stories. Bombay: Screen Unit, 1987.

Manishita Dass. The Cloud-Capped Star: [Meghe Dhaka Tara] (Kindle Location 1387).

Majumdar, Rochona. Art Cinema and India’s Forgotten Futures: Film and History in the Postcolony. New York: Columbia University Press, 2021.

Sarkar, Bhaskar. “Epic Melodrama or Cine-Maps of the Global South.” in Robert Burgoyne (ed.), The Epic Film in World Culture. New York: Routledge, 2011.

–––, Mourning the Nation: Indian Cinema in the Wake of Partition. Durham: Duke University Press, 2009.

Sen, Sanghita. Recovering Indian Third Cinema practice: a study of the 1970s films of Ritwik Ghatak, Mrinal Sen, and Satyajit Ray. Dissertation. University of St. Andrews. 2020.

Vahali, Diamond Oberoi. Ritwik Ghatak and the Cinema of Praxis: Culture Aesthetics and Vision. Springer 2020.