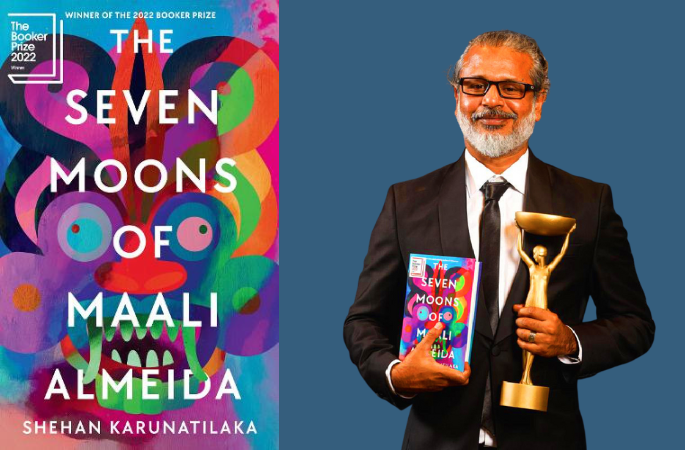

When located geographically, in strife and in conflict there is no peaceful past to remember, in the hope that memory will provide some solace in the traumatic present. Seeking distance from the current situation, trying to make sense of the chaos, we have only another traumatic period to escape to. This is the project undertaken by the 2022 Booker prize-winning novel The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida, by the Sri Lankan writer Shehan Karunatilaka.

Karunatilaka sets the story in the eighties, the time of the civil war. The escape to this period cannot be physical; we can escape only in our minds. Or with our souls, which, Karunatilaka makes possible in this perfectly plotted novel. Okay, so here we are, in the past which is no less terrible than the present. What can we do then, to attenuate the sting? All that we can allow ourselves while remembering, even while reliving a past trauma is humour. So, we laugh with Maali Almeida, the 34- year-old protagonist who is dead right at the beginning of his story. Even the confirmation of his dead state, so to speak, which normally should be a tragedy, the author makes us laugh at. Initially, Maali wonders whether he is asleep or drugged. When he realises that he has been murdered, the writer keeps us laughing.

Maali does not know who murdered him. However, he can guess the motive. As a photographer, he has produced and is in possession of pictorial evidence of the crimes committed in the civil war, the violence perpetrated by the government, by the LTTE, the role of the IPKF, the corruption, and the inefficacy of the media. In possession, now that he is dead, means that the photographs lie hidden under his bed in his family home. His murdered self has been given a period of seven nights to identify his murderer, to get in touch with the sympathetic friend and to reveal to the city of Colombo, and to the entire world, the evidence of the realities of the civil war. After these seven days, he will forget his past life. “They want us to forget” so that nothing is changed.

Memory is important. However, the author also bears in mind that too much of this remembering, this recollection of the past might actually hamper the change that we want to bring about. We know from our own conflict regions that sometimes this strategy of repeating the past events, of discussing the various accords, discussing the various times that a particular group got a raw deal is merely a ruse to keep us from any action that will actually bring about peace. We know that this can go on for decades and that many people lose their lives in this kind of stretching of conflict. Hence the seven moons. A fixed time period. The protagonist does not forget totally and moves on without making amends, without taking some action. In this fixed time of seven nights, he has to act.

The action is located in a created world between life and the afterlife. Again, we will recognise this world, typical of subcontinental waiting or transit areas. The humour is always in the narrative. We laugh at the absurd arguments between corpses. Without the humour, we would not have been able to bear the knowledge that these are innocent people who have been killed in the conflicts. These people, including a Tamilian professor who has been killed just for speaking up, are presented in an absurd, fantastic, way. Their real existence in this absurd form is actually impossible, but we recognise them. Like a very hurtful version of insider jokes, there are some things in this book that all of us, readers from the subcontinent will recognize instantly.

Speaking of subcontinental readers, “What is it to us, Indians? That ‘foreign’ prize.” Recent developments in education policy, and the current atmosphere almost allow the next unsaid words to be heard: “Books written in English, which is, after all, not ‘our’ language”. And yet, the quiet, often solitary lives of bibliophiles all over India are suddenly touched by excitement when The Booker Prize Shortlist is announced. Awestruck; a woman watches the new display that a favourite bookstore has put up. Most of the books she has already read. She makes a quick calculation to see whether she can afford to buy the one she has not. She talks about the books with a friend, knowing full well that the discussion will not give her the ‘likely winner’, but will only confirm what the two women already know about each other – their taste in books. It is that taste, which determines the ‘prediction’.

And yet, under the pretence of expert prediction, we have had, for the past few days, many such discussions about the titles on the shortlist. More importantly, each one of us has in our own way – as an Indian reader, thought about each one of the books in this year’s shortlist.

♦ The Trees by Percival Everett – The book that the judges called “A dance of death with jokes.” To speak about terrible crimes committed in the name of difference, of superiority. So, it is with humour then, that we can speak of unspeakable wrongs.

♦ Treacle Walker, by Alan Garner – This strange book with its painstakingly constructed Structurelessness. The mixed-up, circular structure that may befuddle a western writer, but is so familiar to us. We are curious to see whether this 87-year-old man, the oldest nominee ever, will win. This old man speaks of the treeness of trees. We, who despite our migration for work, never really “left our patch”.

♦ Small things Like These, by Claire Keegan – The judges call her writing measured and merciless. But we know that from her short stories already. We have cried with the Forrester’s daughter. Small Things Like These is the shortest novel on the list. We know Claire Keegan created a world and gave us a deep insight into the characters in her short novella Foster. In Small Things Like These, a story of an ordinary man is all it takes to uncover a wrong inflicted upon the vulnerable, in the name of religion.

♦ Glory, by NoViolet Bulawayo – Political identities, feelings, and social positions of the characters all expressed only by the writing of dialogue, of a unique speech for each character. Without support from descriptions of physical appearances, for every character is an animal. We have met Poonachi, Perumal Murugan’s goat and listened to her talk of caste. We know that these animals will effectively tell the story of political changes, of overthrown governments. It is possible.

♦ Oh, William! By Elizabeth Strout – knowing Lucy from previous books, one knows what she is going through even when she does not say what she feels. Oh William however, is an independent novel, and you can enjoy it, even if you haven’t read My Name is Lucy Barton. You will enjoy the details, as if from real life. Deceptively simple writing. Strout has, once again, accomplished what she does best. In many ways, going deep into ordinary life is equally, if not more challenging than creating fantastic worlds.

And finally, what all of us in our subcontinent were cheering for. The reason we stayed up to hear the announcement at what was 2 AM was for us –

♦ The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida by Shehan Karunatilka – the book that the judges called a whodunnit full of ghosts, gags, and humanity (a bit like our popular cinema, I thought, it has everything). While announcing that the novel has won the Booker prize, the chairman on the jury said, “it’s a book that takes the reader on a rollercoaster journey through life and death right to what the author describes as the dark heart of the world…And there the reader finds, to their surprise, joy, tenderness, love and loyalty,”

And we applaud. From the bottom of our subcontinental hearts. Maybe we think a bit about Strout’s Lucy Barton, who struggles with her class origins as many of us do with our religious/caste origins, about the stories of Claire Keegan which bring out the meaning in every day, and of NoViolet, a woman of colour like us.

But we also know that Karunatilaka deserves the Booker for the way he keeps us engaged and entertained even as he is telling us difficult truths. Like all very local stories which have the maximum universal appeal, The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida will be understood and enjoyed because of the humour, thought about because of its philosophical discourse, and talked about because of this political content, by people throughout the world.