Interpreting a Folio from a Kangra Gita Govinda

Fig. 1: In the Gita Govinda, the sakhi persuades Radha to meet Krishna (c. 1820–1825), Ink and colour on paper, Bequest of Mrs Severance A. Millikin, Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio

This Pahari painting (Fig. 1), a nineteenth-century Gita Govinda belonging to the Kangra School, captured my attention for its impeccably balanced composition — the figures are placed at perfect intervals from each other; spaces around them are filled to an ideal extent by foliage to create two groves; while the remaining space is filled with the earth, water and sky, punctuated by a scattering of gem-like blossoms. These elements are held together by decorative borders, rounding off the precious quality of this painting, which is possibly the work of the artist Purkhu, whose style has been described as having “a remarkable clearness of tone” (Baden Powell qtd. in Goswamy and Fischer 369). The formal perfection of this folio, which nevertheless sacrifices naturalism for its immaculateness, led me to ponder on the deep, even devotional contemplation that the artist must have bestowed on his subject. In this essay, it is my endeavour to explore three aspects of this painting: its style; its content (as just one painting from a series of scattered folios that belong in a set); and the philosophical foundation of the Gita Govinda that finds expression in it.

The Gita Govinda

The Gita Govinda (The Song of Govinda) is a twelfth-century devotional poem — a romantically charged pastoral — composed in Sanskrit by Jayadeva, a poet-saint from eastern India. The poet used Radha and Krishna’s passion to express the complexities of human and divine love. Soon after its composition the Gita Govinda swiftly gained popularity throughout the subcontinent and remains a source of religious inspiration even in contemporary Vaishnavism (Garimella 76). In it, one vasanta (spring) day, Nanda, Krishna’s stepfather, asks Radha to accompany the young Krishna, as the cowherds of Vrindavan leave for the pastures. Once they enter the forest, Krishna seduces Radha and makes love to her. But after this encounter, he deserts her to dally with other cowherdesses. Radha longs for Krishna’s exclusive love as she waits in vain with mounting jealousy, anger and despair. Her sakhi (female friend) describes Radha’s suffering to Krishna and eventually helps in reuniting them. Though the poem has been interpreted as an allegory for the human soul’s love for god, it is equally well-known for its candid eroticism “incorporating language and situations from the existing genre of erotic taxonomies describing lovers, love situations, and go-betweens” (Garimella 76).

The Krishna mythology is ancient; before the Gita Govinda he had appeared in epic and Sanskrit court poetry variously as a great ruler, counsellor and an avatar of Vishnu. The young Krishna had been hidden away among cowherds in order to protect him from his demonic uncle, Kamsa, and his youthful episodes as a divine lover became the focus of medieval devotional cults that emphasized erotic mysticism. Jayadeva reshaped and further enriched the Krishna lore by isolating Radha as his primary lover, relegating the other gopis to either rival or sakhi, thereby creating through his dramatis personae the subject, object and intermediary for the pursuit of Krishna Shringara. The Gita Govinda became the foundational text of the Krishna devotion as part of bhakti movements that were widespread across northern India in the sixteenth century (Garimella 76), and it was to be depicted through miniature paintings over the centuries.

Pahari Painting

By the mid-seventeenth century, a distinct Rajasthani school of miniature painting had emerged. As the Mughal empire went into decline during the eighteenth century, the hill states of Basohli, Guler, Kangra and Jammu, ruled by Rajputs, came into being in the foothills of the Himalaya. Unlike the urban and bureaucratic Mughal empire, these Rajput states were dominated by local nobility, which indicates why regional elements constantly surface in Rajput architecture and painting (Mitter 143). Along with the popular Ramayana and Mahabharata there was a fascination for themes from the Baramasah, Nayaka and Nayika-bheda, Ragas and Raginis and above all the Bhagavata Purana and the Gita Govinda (Vatsyayan 9). In his 1916 classic, Rajput Painting, Ananda K. Coomaraswamy wrote of Pahari painting, “… their ethos is unique … the arms of lovers are about each other’s necks, eye meets eye, the whispering sakhis speak of nothing else but the course of Krishna’s courtship, the very animals are spell-bound by the sound of Krishna’s flute and the elements stand still to hear the ragas and raginis. This art is only concerned with the realities of love; above all, with passionate love service, conceived as the means and symbol of all union” (qtd. in Goswamy and Fischer 7). However, as Pahari paintings were not signed by their artists, not one painter found mention in Coomaraswamy’s pioneering work. Following B.N. Goswamy’s doctoral dissertation, the 1960s saw a shift in emphasis from classifying the paintings geographically to individual painters, their family styles or kalams and social context. Hence we learn of the Pahari masters of whom Purkhu of Kangra, to whom this folio is attributed, was one.

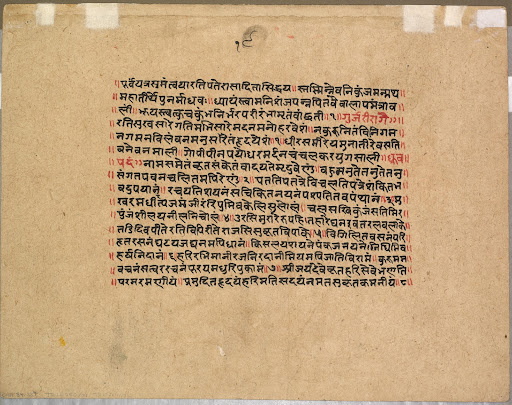

Fig.2: The inscription on the verso in Devanagari script

The Folio and the Unfolding of Bhakti

The Gita Govinda comprises twelve chapters or sargas that are further divided into prabandhas containing couplets grouped into sets of eight. These couplets, known as ashtapadis, are meant to be sung. Jayadeva assigned a raga for each song indicating the mood and pervading emotion of the verses. In this folio, number nineteen, as indicated on top of the inscription on the verso (Fig. 2), there is a rigorous relation between text and image as the sakhi, commanded by Krishna, pleads his case to Radha. In the fifth chapter, “Lotus-eyed Krishna Longing for Love”, Krishna tells the sakhi, “I’ll stay here, you go to Radha! / Appease her with my words and bring her to me (Miller 90)!” So the sakhi goes to Radha, and at the end of the tenth song (which is to be sung in raga Desavarudi), the sakhi says to Radha, “Madhava still waits for you / In Love’s most sacred thicket, / Where you perfected love together. / He meditates on you without sleeping, / Muttering a series of magical prayers (Miller 92).” The inscription on the folio begins with this description of Krishna’s state where he is metaphorically struggling to find himself in the forest of samsara (the material world). True to the text, we see on the right of the painting, which has been topographically divided along a diagonal axis by a tree just beyond the Yamuna river, a wakeful Krishna distractedly playing the flute in a thicket while arranging a bed of leaves.

In another grove on the left of the page we observe the sakhi next to Radha with one hand pointing in the direction of Krishna and the other, delicately, to her own heart as she makes her entreaty described in the eleventh song (which is to be sung in raga Gurjari): “He ventures in secret to savour your passion, dressed for love’s delight. / Radha, don’t let full hips idle! Follow the lord of your heart! / In woods on the wind-swept Jumna bank, / Krishna waits in wildflower garlands. / He plays your name to call you on his sweet reed flute. / … Hari is proud. This night is about to end now. / Speed my promise to him (Miller 92, 93)!”

Pushing the top edge of the painting, we see a dramatic, sunset-red swash across the sky that looks like the hem of a curtain that will drop the dark blue night upon the forest below. The vernal forest on the “Jumna bank” is, as described elaborately in song three of the first chapter, “Joyful Krishna” (which is to be sung in raga Vasanta), replete with fresh leaves, crying cuckoos, mimosa branches and budding mango trees that “tremble from the embrace of rising vines (Miller 75).” In Vrindavan, Krishna’s madhurya (an expression of inner beauty) is universally present, or in the words of the philosopher Vallabhacharya, “akhilam madhuram”. The honeyed notes of his flute bring all under his spell — the gopis, the birds and the bees, the river, vines and blossoms. Amid this spectacle of nightfall we take a closer look at the iconography of the bejewelled Krishna in yellow silk; his moramukuta (peacock feather crown) crowning his head, a wildflower garland around his neck, his ghanashyam body, the colour of rain clouds yet luminous, “like sunlight inciting lotuses to bloom” (Miller 72). And so the lotuses bloom on the Yamuna river, which washes the lowermost register of the painting in nearly the same blue as Krishna’s body and topped by a white line that indicates its bank — a signature feature of Purkhu’s work and reminiscent of the work of his predeccessor, Manaku. The sacred river of Krishna’s childhood provides on its banks dense groves of kadamba, tamala, bakula and other trees which the artist has rendered with his characteristic “profusion of stylized blossoming sprays of flowers that cascade down” (Goswamy and Fischer 372). Surrounded by this suggestion of lushness and fragrance, her face spot-lit by the artist as though bathed by moonshine, sits Radha, the supreme nayika, the symbol of shringara rasa. With her sakhi she goes through the many moods of a woman in love, and in the process she humanises Krishna from a divine being to a romantic hero or a nayaka as we realise, that even the venerable Krishna is susceptible to the anguish of longing (Dehejia, H. 3). In shringara bhakti, the way to jnana or knowledge, is through an earthy, sensual love in which to live is to love, and to love is to know. Here, “tender-limbed” Radha becomes a metaphor for the sensuality of prakriti (substance) — the vehicle of erotic and devotional expression — who will enlighten the questing purusha (spirit) (Dehejia, H. 6).

“Krishna is watching you Radha! / Let him celebrate your coming (Miller 94).” urges the sakhi in the last lines of the fifth chapter. In the optical centre of the folio marked by bright red blossoms, there is Krishna again, peeping from behind the foliage as he waits to see if Radha has been placated. This device of repeating the appearance of a protagonist, known as the continuous narrative mode, was used by Rajput painters in a departure from the standard monoscenic mode used by Mughal artists, in which each page depicts only one scene from a narrative. In the continuous narrative mode, consecutive time frames are presented within a single visual field without any dividers to distinguish one time frame from the next, and the action flows “continuously” across the page (Dehejia, V. 304, 305).

“Go to the darkened thicket, friend! Hide in a cloak of night (Miller 92)!” directs the sakhi, the one who is mediating for these lovers who have been placed at the ends of the page, seemingly too distant to ever reunite. As the devotee sings the sakhi’s imploring words throughout the Gita Govinda (for it is a poem that is meant to be performed), s/he merges with this singularly important character and experiences through her, Krishna’s passion and transfers the same emotion to the ecstatic adoration of Krishna. Using the immediacy of the senses to arrive at the ultimacy of the spirit, or brahmajnana, devotees are brought gently into the fold of bhakti and “on purely aesthetic grounds, the Gita Govinda rises from mere sensuality to an exalted spirituality” (Dehejia, H. 5). The painter too becomes one with the poet as they both help the viewer to achieve Jayadeva’s version of shringara bhakti — knowledge by devotion combined with rasa — to experience Brahman or ultimate reality. In the tradition of Shuddhadvaita thought, the separate entities of poet, painter, devotee and their piety come together in the celebration of Krishna, becoming Krishnamaya or full of the essence of Krishna. This enchanting world created by the Pahari painter “is not unreal or fanciful, but a world of imagination and eternity, visible to all who do not refuse to see with the transfiguring eyes of love” (Coomaraswamy qtd. in Goswamy and Fischer 7). Like the devoted painter, it is this world that a rasika is privileged to enter through the contemplation of this painting.

Works cited:

Dehejia, Vidya. “The Treatment of Narrative in Jagat Singh’s ‘Ramayana’: A Preliminary Study.” Artibus Asiae, vol. 56, no. 3/4, 1996, p. 303. Crossref, doi:10.2307/3250121.

Dehejia, Harsha. “Radha in Gita Govinda.”

Garimella, Annapurna. Love in Asian Art & Culture. “A Handmaid’s Tale: Sakhis, Love, Devotion, and Poetry in Rajput Painting.” Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. Smithsonian Institution, 1998.

Goswamy, B.N., and Fischer, Eberhard. Pahari Masters: Court Painters of Northern India. Niyogi Books, 2012.

“Krishna flirting with the Gopis, to Radha’s Sorrow: Folio from a Gita Govinda Series.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/76075. Last accessed on 04/03/2021.

Miller, Barbara Stoler. Love Song of the Dark Lord: Jayadeva’s Gitagovinda. Columbia University Press, 1997.

Mitter, Partha. Indian Art (Oxford History of Art). Oxford University Press, 2001.

“Sakhi Persuades Radha to Meet Krishna, from the ‘Lambagraon’ Gita Govinda.” Cleveland Museum of Art, www.clevelandart.org/art/1989.334. Last accessed on 04/03/2021.

Vatsyayan, Kapila. The Darbhanga Gita-Govinda. Abhinav Publications, 2011.

This article was first written by Rukminee Guha Thakurta towards the fulfilment of the Indian Aesthetics Diploma at Jnanapravaha, Mumbai, in November 2020.