Stigma to mental health is well documented across all cultures, particularly within the South Asian community. Stigma to cancer is also highly prevalent among the South Asian community, in contrast to the Western world where cancer is perceived as a misfortune that needs to be fought. In this feature, we discuss the root of stigma and its subsequent effects.

Our health is important to all of us. It frequently dominates the media and subsequently our politicians’ agenda. Cancer is particularly emotive, with all of us likely to be directly affected or know someone close to us to be affected by this terrible disease.

I practice as a haematology trainee in the UK, a nation celebrated for its cultural diversity. From both personal and professional experiences, I have noticed varying perceptions of illness among the different communities here.

Within the South Asian community, I have noticed a palpable notion of ‘shame’ in attitudes to illness, particularly cancer and mental health, resulting in the need to hide such a condition from friends and family.

The notion of stigma, whereby a diagnosis of cancer is seen to be culturally unacceptable, is confirmed in numerous literature.

Stigma and Illness among South Asians

Blame appears to be a common theme. Perhaps this stems from the interpretation of Hindu and Buddhist philosophies together with the hierarchical caste system. Rebirth and reincarnation are key tenets of both.

A simplistic interpretation is that suffering is a direct result of karma or fate – hence “I am ill because I have done something bad in a previous life”. However one of the Four Noble Truths, a paramount teaching of Buddhism, is that “Life, itself is suffering”.

Another focus is on the impermanence of life and to not fixate on the past or future. So why have guilt over deeds committed in a previous life? And why is there this stigma predominantly in relation to cancer and mental health, not other diseases?

A similar attitude can also be seen in Christianity and Islam in traditional societies, where illness is seen as God’s will. Within Christianity, particularly Catholicism, illness can be seen as the punishment for sins. Conversely, though, the subsequent response is often to view illness as a test of your faith in God. Or rather than suffering being related to one’s own self, it is more related to a larger aspect of Evil.

Stigma and the Consequences

Religion does not entirely explain the issue of stigma to illness within the South Asian community. On discussing this issue with friends of different nationalities and religions within the Indian Subcontinent, a common theme appears – we all have experiences of patients hiding an illness from close friends and the extended family. Perhaps it is a fear of gossip, shame or not wanting to feel pity.

This also falls vice versa, for the family to hide a diagnosis or the severity of a condition from the patient. Indeed this is reported in the literature, with almost 50% of Indian patients undergoing treatment for cancer treatment found to be unaware of their diagnosis or treatment.

Collusion is common to many societies but in the South Asian community, doctors may be urged to partake in the deceit. This is partly due to differences in the doctor-patient relationship between South Asian and Western cultures.

Western doctors conduct a consultation based on shared decision-making as opposed to a more traditional paternalistic approach in South Asia. The medical regulatory body in the UK, the General Medical Council, advises doctors to only withhold information required for decision-making when suspecting serious harm to the patient. This guidance is based on the principle of maintaining a patient’s autonomy.

Collusion is rooted in good intentions of trying to protect the patient, oneself, other loved one/s or can even be an act of denial. Perhaps not knowing the full truth helps formulate a more positive outlook and minimise feelings of shame, worry or depression.

However, it often results in distrust, shock and upset following poor communication for the patient or affected loved ones. Studies have demonstrated that Indian cancer patients living in both India and Britain wish to know the nature of their diagnosis, 94 percent in an Indian study and 99.6 percent in a British setting.

This surprisingly high statistic likely reflects our increasingly modernising society.

Another major consequence of stigma is isolation. The affected person and family isolate themselves, not sharing their emotions and experiences, weighed down by guilt, shame or fear of gossip. Common coping methods resorted to by a patient after a diagnosis of cancer among the South Asian community involves denial, resort to religion, attributing it to fate or karma, and sheer helplessness.

However using these techniques appears ineffective, with the resolution of fears in less than 40%. Isolation only worsens this, leaving patients and their carers vulnerable to depression and anxiety.

Real Life Stories

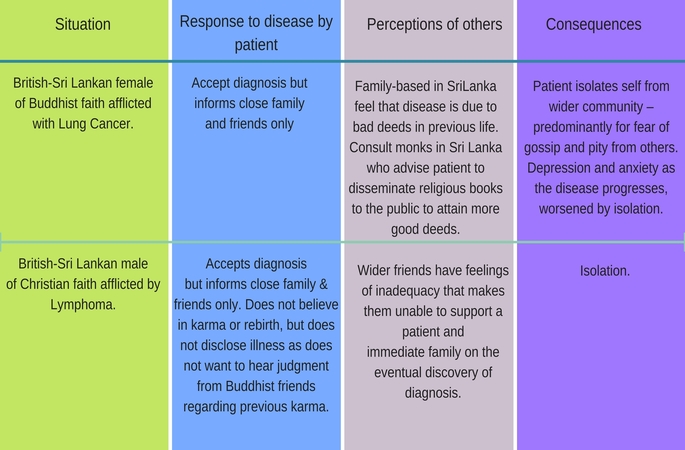

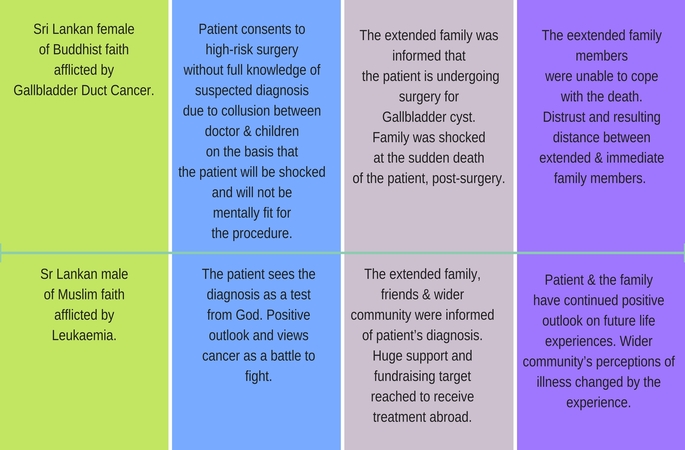

I will illustrate my musings on the above by discussing a few real-life stories based on personal encounters. Each case is based on a Sri Lankan affected by cancer. Based on religion and site of habitation, the experiences and consequences have their own similarities and differences.

All cases discussed are based on personal experiences, not professional, and are fully anonymised.

Family Support, Culture and The Reflection

The above table focuses on the negative consequences of stigma, particularly, isolation in cancer patients. Similarly, those suffering mental health disorders also face stigma, where a mental health disorder can be seen as a curse.

Despite this taboo, psychiatrists have noted improved outcomes in schizophrenics of Asian origin compared to their Western counterparts. Birchwood et al cite this due to support through extended family structures, greater opportunities for social reintegration and more positive constructions of mental illness.

For example, rather than an illness, depression is instead viewed as part of the ups and downs of life. Even if not aware of an illness, the close network via extended family and wider community results in much greater support for Asian patients compared to their Western counterparts.

Likewise, where family support is available for cancer patients, the patient’s burden would be significantly lessened in contrast to Western patients where principles of autonomy, empowerment and individual responsibility may be detrimental to the patient.

Another point for reflection is on the status of doctors in the Asian subcontinent. Interestingly, those who treat illness, doctors remain hugely revered as professionals in the South Asian community.

I feel it is now our duty as doctors to recognise the stigma that those of South Asian heritage may face. One way of breaking down stigma is through education, to educate the public that illnesses stem from physiological imbalances in our bodies.

Cancer cells arise due to mutations, changes in our genetic code.

Depression, anxiety and schizophrenia are just a few mental health conditions known to be related to imbalances in neurotransmitters. We should focus on education to spread awareness and understanding of the causes of disease, perhaps with programmes among the community and religious leaders.

Culture plays an important role, whether influenced by religion or not in this stigma. As a British born doctor with Sri Lankan heritage, there are positives and negatives to both cultures I am aware of. Aiming to take positives from both cultures, we should strive to lessen the stigma with education whilst continuing our support of our loved ones.