An Extract from The River, The Town

Very long time ago when the river used to be wide and deep. I have always seen it as a thin stream flowing weakly over the ground. When my friend Juman is extra hungry he says it looks like a gray intestine.

It is a warm afternoon but we run until we reach it, and then we go down the incline onto the hard, dried ground, toward the stream. “I think Aab likes me,” Juman says.

Kawsar laughs at him. “You think everyone likes you,” he says. “She said I could copy her math work.”

We are by the water. We are running again, not talking anymore. After two kilometers or so we stop but the stream goes on. We turn around and walk, stopping to scoop water into our mouths when we are thirsty. We will try not to be thirsty at our homes, the water there is too little. This week, only one tanker has come to the Town, and the driver said each person could not take more than twenty liters.

At home is my mother, sharp and thin as a knife. She crosses her arms and asks me where I was. Her tone makes me shrink inside; I hate having the same reaction to her voice at seventeen as I had at seven. “Just out with my friends,” I tell her.

I don’t look at her face because I know all its features will be hard and stark; her chin will be bony, her hair more gray than black. Her clothes will be the oldest clothes I have seen on anyone, even the maasi who go to clean homes. The picture of destitution. There is a slight movement, and my glance flicks up to her. She has tightened her arms and narrowed her eyes.

“Were there girls there? I’m sure that haraam zaada Juman must have arranged for you to meet some girls. Did he get you cigarettes? Or his father’s bottle to drink from?”

“It was just us, we went to the river. We didn’t do anything.” Then my school bag slips off my shoulder and falls by my feet. I reach down to pick it up but my mother leaps forward and snatches it out of my hand. She pulls the zip and shakes the bag over the floor.

I hold my breath as the objects fall out: books, a pencil, a few exercise books, a ruler, a scrap of paper. What else is there? My mother puts her hand inside and pulls out a cigarette. The cigarette is from weeks ago, from an afternoon when I had tried one with Kawsar and Juman and then put the extra one in the bag, forgetting all about it.

To my mother, it is proof of everything sordid she imagines all day long. She sounds almost happy in her triumph. “You think you can hide your dirty self from me, do you? You think you are oh so big now,” and here she puts her hands on her hips and sticks out her chest and pulls a grotesque face, “Mr Big Smoker Man with a scrawny moustache.”

I wrap my anger around my organs, protecting them. I remove from my mind any images from the afternoon when I had laughed with my friends, because that is a false me, and this is the real me, the person that I am inside this house, in front of this woman. But the longer she goes on speaking the thinner that protection gets until I fear that my rawness will start to be exposed. Abruptly, I run into my room. From a space behind my desk, I bring out the key I had gotten made in secret. With shaking hands, I lock the door.

From the other side, I can still hear my mother. “Have you seen your face in the mirror? Do you think that’s a moustache? You think that thing above your lips makes you a full-grown man who doesn’t have to follow his mother’s rules anymore? You’re going to be like Juman’s father, sleeping with whores from the City and drinking. That’s all you’ll be.”

There is nowhere in my room to block her sound. Just the desk with the single drawer, a small cupboard, and a narrow bed with a worn-out sheet. I pull it over my head, lying on the mattress with faded outlines of urine stains from when I was a little boy. I stay there until I hear my father come home at night.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

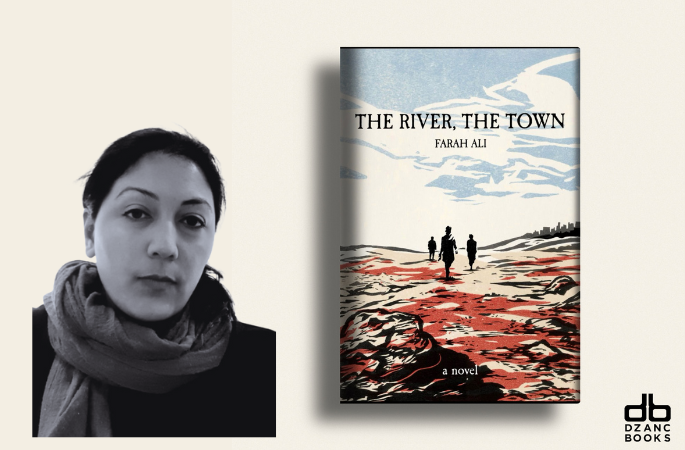

This extract offers a glimpse Ali’s storytelling and the profound humanity that underpins her work.

You can buy the Novel here https://www.dzancbooks.org/all-titles/p/the-river-the-town-by-farah-ali

Farah Ali, originally from Karachi, Pakistan, is a gifted writer whose work captures the nunaces of human relationships, social inequities, and emotional resilience. Now based in London, Ali’s literary voice has earned critical acclaim, with her short stories featured in prestigious collections like the Pushcart Prize Anthology and her debut collection, People Want to Live, published by McSweeney’s Books.

Her debut novel, The River, The Town, is a poignant exploration of life in rural Pakistan, where drought and poverty shape the daily realities of its inhabitants. Spanning the years 1966 to 1998, the novel follows Baadal, a young man seeking solace and hope amidst the crumbling relationships and hardships that define his world. Ali’s prose is stark yet tender, bringing to life the silent struggles of a family torn apart by indigence and the relentless pursuit of a better future.

In The River, The Town, Ali juxtaposes the harshness of economic despair with the enduring strength of human connections, making her work both timely and timeless. Her ability to weave intimate narratives within broader social contexts makes her an essential voice in contemporary South Asian literature.

Founded in 2006, Dzanc Books champions innovative writing and fosters literary communities, publishing award-winning fiction and nonfiction from acclaimed authors like Roy Kesey, Yannick Murphy, and Laura van den Berg. Beyond publishing, Dzanc supports literary education through their Writers-in-Residence Program in public schools, hosts the Disquiet International Literary Program in Lisbon, and awards three annual Dzanc Prizes for excellence in fiction and nonfiction. Supported by the National Endowment for the Arts and Ann Arbor Community Foundation, Dzanc connects readers to bold, boundary-pushing literature, distributed widely through Publishers Group West.